Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Born Albi, Tarn, 24 Nov 1864; Died Château de Malromé, nr Langon, Gironde, 9 Sept 1901.

French painter and printmaker. He is best known for his portrayals of late 19th-century Parisian life, particularly working-class, cabaret, circus, nightclub and brothel scenes (see fig.). He was admired then as he is today for his unsentimental evocations of personalities and social mores. While he belonged to no theoretical school, he is sometimes classified as Post-Impressionist. His greatest contemporary impact was his series of 30 posters (1891–1901), which transformed the aesthetics of poster art.

1. Life and work.

(i) Family life and early training, to 1882.

Many of the defining elements of Toulouse-Lautrec’s life and work came to him at birth. His parents, Comte Alphonse-Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec (1838–1912) and Comtesse Adèle Zoë Tapié de Céleyran de Toulouse-Lautrec (1841–1930), were first cousins. From them he inherited wealth, an aristocratic lineage, artistic talent and a genetic disorder that would leave him dwarfed and crippled from early adolescence.

Except for one year, Toulouse-Lautrec was educated at home, by occasional tutors and by his mother, with whom he developed a love–hate relationship that was a continual source of conflict for him. His brother Richard had died in infancy and she served and protected her surviving child with well-meaning but iron-willed vigilance; they slept in the same bed until he was eight or nine years old, and even after Toulouse-Lautrec was an adult, his mother lived much of the year close by his studios. When they were in the same city he dined with her almost daily. His father was nearly always absent. A profoundly eccentric man, subject to unpredictable mood-swings resembling symptoms of manic-depressive disorder, the Count spent his time either living in quasi-isolation, deeply involved in all forms of the hunt, or displaying comically attention-seeking behaviour such as bathing naked in his brother’s courtyard or driving his carriage through the streets of Paris with cages of hunting birds—owls and falcons—swinging from the rear axle, so they ‘could get some air’. A superb athlete, the Count also was reputed to be an incorrigible womanizer, favouring housemaids and peasant girls. As a child, Lautrec quickly learnt that he could not compete with such a colourful figure. ‘If Papa is there,’ he commented to a grandmother, ‘one is sure not to be the most remarkable.’ He was right. No matter how exhibitionistic or scandalous the adult Lautrec chose to be, he could never outdo his father in gratuitous eccentricity. Many of Lautrec’s passions—drawing and sketching, non-conformist behaviours such as dressing in costumes, collecting eccentric curios and a fascination with animals and women—reflected his father’s habits.

Beginning around age ten Toulouse-Lautrec suffered from severe bone pain and was hospitalized for more than a year. In 1878 he fell from a low chair and broke his left thigh bone and in 1879 the right one. His growth stopped at 1.52 m. By age 16 he was permanently dwarfed, and the bone breaks had crippled him so that as an adult he walked as infrequently as possible, in a kind of duck-like stagger using a cane.

Throughout his childhood Toulouse-Lautrec drew and painted alongside his father or one of his uncles, all talented amateur artists. Art became his strongest weapon: with it he was able to fight the depression of long convalescences and the well-meant but stifling protectiveness of a concerned family. He drew constantly, covering schoolbooks and sketchbooks with drawings of animals and caricatures of people. He lived surrounded by horses and dogs, his father’s hunting birds and his grandmother’s pet parrots and monkeys. He had a striking talent for accurate observation of animal and human movement, which has been described as the ability to capture progressive stages of motion in one image. Recognizing his talent, his parents arranged for him to have early training from his uncle Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec (1840–1915) and from a deaf-mute sports-artist friend, René Princeteau (1844–1914), who taught him to draw horses. When it was apparent that he was irretrievably handicapped, his parents allowed him to go to Paris to study art.

(ii) Success and decline, 1882–1901.

In 1882 Toulouse-Lautrec moved to Paris with his mother to study first with Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) and then with Fernand Cormon (1845–1924). He was close to the Cloisonists Louis Anquetin and Emile Bernard and to Vincent van Gogh, all of whom worked with him at Cormon’s. At age 19 he received his first commission, to illustrate Victor Hugo’s La Légende des siècles, although his work was finally not used. After some five years of formal academic training, he had become expert in rendering perspective and volume, but in his own work he freely abandoned the conventions to explore other possibilities. Unlike many of his friends, Toulouse-Lautrec never joined any formal theoretical school, although his work shows the clear influence of Edgar Degas, Honoré Daumier and Jean-Louis Forain among others. He later befriended the Nabi painters Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard, whom he met through La Revue blanche, a magazine that published their work as well as his own. Toulouse-Lautrec’s work also shows the influence of Japonisme.

In January 1884 Toulouse-Lautrec set up his own studio in the Rue Lepic, Montmartre, a quartier of Paris his mother considered both scandalous and dangerous. It was a haven for the poorest, most marginal members of society and since the 1850s, due to its low rents, had been a neighbourhood of predilection for artists. By 1880, a series of dubious nightclubs at the foot of Montmartre had earned a reputation for wildness and bohemianism. Toulouse-Lautrec and a group of artist-friends quickly developed a highly visible lifestyle, visiting galleries and museums in groups, meeting in cafés to argue loudly, dressing in costumes to attend the popular bals masqués, sharing studios and models and generally enjoying all the excitement Paris had to offer. For the rest of his life Toulouse-Lautrec lived in Montmartre (although he took long trips to the south of France), painting friends and models or working from sketches done in the evenings in the Moulin Rouge and other nightspots.

An early tendency to abuse alcohol quickly led Toulouse-Lautrec into hopeless alcoholism. Often drunk, he behaved outrageously, disrupting the bars and dance-halls. Because of his conspicuous appearance, unpredictable behaviour and ever-present sketchbook, he became a well-known figure at such places as the Moulin de la Galette, the Elysée Montmartre and the Chat Noir. His raucous lifestyle offended his family, causing constant conflict not only over money, but also over his right to use the family name, his artistic style and even his subjects—more particularly perhaps because they were also his friends. He had intensely loyal friendships with people of widely varying milieux: aristocrats; artists; left-wing intellectuals and writers; side-show, circus and nightclub performers; actors; professional athletes; milliners; prostitutes; and coachmen. His father repeatedly tried to convince him to use a pseudonym. Over the years the painter used a series of names, particularly the anagram ‘Tréclau’. In the long run he signed himself H. T. Lautrec or just with his initials, h. t. l.

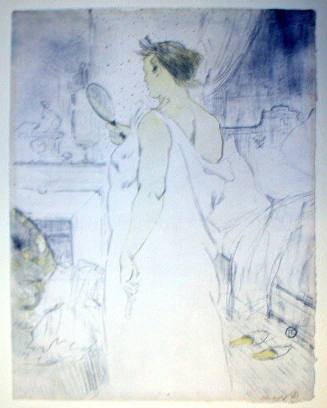

Despite his physical handicaps, Toulouse-Lautrec always refused to hide from public view. He had developed a hatred for the hypocrisy and sentimentality that masked people’s treatment of him and, as he was coming to realize, all their human relations. Always an aristocrat, he now became an iconoclast, resolutely destroying false pretensions with a sharp word or a sabre slash of pencil on paper. He was increasingly sensitive to anyone’s attempts at putting on appearances. His greatest artistic skill perhaps was the psychological acuity with which he portrayed facial expressions and body language: the ability to get behind his models’ surface defences and petty vanities to show their vulnerabilities and vices. His portraits capture hidden emotions: hostility, indifference, desire, self-indulgence. His artistic honesty created some tense moments with his models, who sometimes refused to continue posing for him, afraid of his unflattering ability to reveal their true feelings. His subject-matter was almost entirely autobiographical; he primarily depicted the people he knew, often shown in his own studio. After 1886 he tended also to pose them in settings with a social context: in Montmartre’s streets, bars and dance-halls or in the circuses, racetracks, sports arenas and brothels of Paris (e.g. Woman before a Mirror, 1897 and The Sofa, 1894–6; both New York, Met.). Today, his images of cancan dancers and nightclub singers, prostitutes lining up for their medical examinations or waiting, bored, for clients, mark our impressions of turn-of-the-century Paris.

In spite of his irregular and distracting lifestyle, and perhaps in part because he was so visible, success as an artist came quickly to Toulouse-Lautrec. As his work began to sell well, he took pride in keeping separate bank accounts for his sales and for his monthly allowance from his parents. Although his allowance (c. 15,000 francs per annum) was perfectly adequate, he was always short of money, a by-product of extravagant tastes and lavish generosity. He received critical acclaim from such major art critics as Roger Marx, Gustave Geffroy and Arsène Alexandre. In addition, he was remarkably productive. By age 21 he was selling drawings to magazines and newspapers; he also illustrated books, song sheets, menus and theatre programmes. After being in his first group show (Pau) in 1883, he exhibited in group shows in Paris at the Salon des Arts Incohérents (1886, 1889) and at the Exposition du Petit Boulevard organized by Vincent van Gogh in 1887. He participated a number of times in the annual exhibitions of Les XX in Brussels and at the exhibitions in Paris of the Société des Peintres-Graveurs Français at the Galerie Durand-Ruel, Louis Le Barc de Boutteville’s exhibitions of the Estampe originale and Impressionists and Symbolists, the Cercle Artistique et Littéraire Volney, the Société des Indépendants and the exhibitions of the Journal des cent. Although he exhibited in various places and sold works through a number of dealers, beginning in 1888 he became affiliated to Boussod, Valadon & Cie through Theo van Gogh (1857–91) and he remained with them thereafter. He shared their gallery with Charles Maurin (1856–1914) for his first two-man exhibition in 1893 and had his first one-man show in 1895 at the same gallery, later called Manzi-Joyant after it was acquired by Michel Manzi and his childhood friend Maurice Joyant (1864–1930). He also exhibited at their London branch in 1898.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s success with the artistic avant-garde was equalled by his popular audience. From 1886 his work was placed on permanent exhibition in one of his habitual hangouts, a Montmartre cabaret known as Le Mirliton, and in 1889, for its grand opening, the Moulin Rouge nightclub hung his painting At the Fernando Circus: The Equestrienne (1888; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) in the entrance hall. In 1891 the nightclub itself was the subject of Toulouse-Lautrec’s first poster, Moulin Rouge, La Goulue, a work that made him famous all over Paris. Over the next ten years he did a great deal of commissioned work: posters (see fig.), portraits, book illustrations (see Book illustration, §IV, 2), advertisements, stage décors and the covers of sheet music. He also made brief forays into the Art Nouveau crafts movement, experimenting with ceramics, book-binding and stained-glass windows. The Moulin Rouge continued to feature in a number of works, including Jane Avril Leaving the Moulin Rouge (1892; Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum) and At the Moulin Rouge (1896; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.).

By 1893 those who knew Toulouse-Lautrec were aware of his alcoholism and several friends reported that he was also suffering from syphilis. His behaviour became increasingly erratic and eccentric. He lived briefly in several brothels, narrowly escaped violent physical confrontations while drinking and was arrested at least once. He was institutionalized briefly in 1899, an event that caused substantial outcry in the newspapers. In 1901 he suffered a stroke while on holiday at Arcachon and was taken to his mother’s house, where he died shortly before his 37th birthday.

In his short life Toulouse-Lautrec produced a phenomenal quantity of work. The 1971 catalogue raisonné of his oeuvre, which even before its publication was recognized as incomplete, lists 737 canvases, 275 watercolours, 369 prints and posters and 4784 drawings, including about 300 erotic and pornographic works. Although important original works are held by museums and individuals throughout the world, the largest body of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work was donated to form the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi by his mother after his death. A complete set of his prints and posters (including all states of each work) is in the Cabinet des Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

2. Working methods and technique.

Toulouse-Lautrec freely adopted any technique or style that helped him to attain a desired effect, from classical composition to Impressionist colour theory. His artistic goals remained highly eclectic and personal. He was interested in doing art, not talking about it, and he believed rules were to be broken as he desired.

In his painting and drawing, Toulouse-Lautrec worked in oils, watercolour, charcoal, pastel, ink and, very occasionally, coloured pencils. He favoured artificial rather than natural light and seemed to enjoy ironically posing subjects in contexts where they felt ill at ease (e.g. Golden Helmet, c. 1890–91; Philadelphia, PA, Walter Annenberg priv. col.; Redhead in a White Blouse, c. 1884; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.). Working in oils, he often sketched the original outlines with a brush in intense blue or green, allowing those lines to show through subsequent layers of translucent paint to give the finished work a rapid, sketchy quality, which is sometimes enhanced by the presence of bare canvas and undeveloped areas of composition. Imitating a technique developed by Jean-François Raffaëlli, he often painted on raw cardboard à l’essence (‘with solvent’), using oil greatly thinned with turpentine. The absorbent surface gave the paint a powdery, almost chalky texture as it dried (see fig.).

Toulouse-Lautrec made a few monotypes and drypoint engravings, but his important contributions to printmaking are in the field of lithography and most importantly in the colour poster. His experiments in lithography included spattering and the use of gold dust, as in Miss Loïe Fuller (1893; see Prints, §III, 6), both based on Japanese techniques (see Japan, §IX, 3(i)). His use of large, flat areas of colour and stylized shapes (e.g. the cape in Aristide Bruant, 1893; or the high-kicking legs in Mlle Eglantine’s Company, 1896) makes posters that are not only immediately comprehensible to the passer-by but also function as works of social and artistic complexity, full of visual commentary on society and references to other works of art. In some prints his coloured shapes dominate the work as abstractions, moving it beyond the purely representational (see Poster, §II, 2).

Possibly as a result of his disdain for the kind of art that won prizes at the official Salon, Toulouse-Lautrec developed an absolute hatred for varnished painting, for any surface that was falsely sealed and glossy. To him the varnish and affectation of such works symbolized the hypocrisy and sentimentality that surrounded bourgeois social conventions.

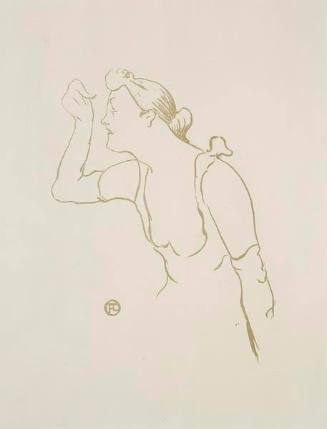

Repetition is characteristic of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work. He repeated stories, acts, images. Occasionally he literally traced the same lines over and over. He is said to have gone 20 nights in a row to see Marcelle Lender (1869–1927) dance the bolero in the comic opera Chilpéric, because, as he explained, she had a beautiful back. Often his work represents a series of studies of the same model; there are, for example, numerous paintings of ‘La Rousse’, a model named Carmen Gaudin (?1866–1920). He had a series of ‘furias’ as he called them—passionate attractions to a person, place or activity, which would dominate his life and art for a time and just as suddenly disappear. There are drawings, paintings, posters and lithographs of music-hall performers La Goulue (Louise Weber, 1870–1929), Jane Avril (1868–c. 1932; see fig.) and Yvette Guilbert (1867–1944; e.g. 1894; Albi, Mus. Toulouse-Lautrec), each in her turn.

After Toulouse-Lautrec was released from the asylum in 1899, his palette moved from the clear, bright colours characteristic of most of his previous work to looming contrasts of dark and light, increasingly marked by blood tones, dense brushstrokes and impasto.

Julia Bloch Frey. "Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T085831 (accessed March 8, 2012).