Bernardo Strozzi

Italian, 1581 - 1644

Italian painter. He was one of the most influential Italian painters of the early 17th century, important to developments in both Genoa and Venice. He is known for religious works, genre scenes and portraits, and his powerful art is distinguished by rich and glowing colour and broad, energetic brushstrokes.

1. Genoa, c 1595–1630.

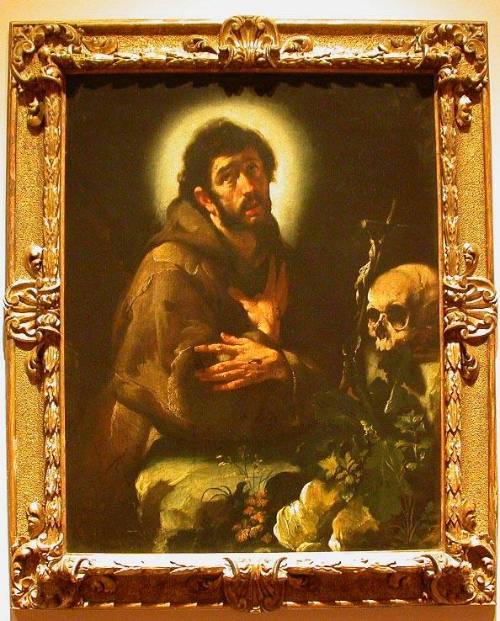

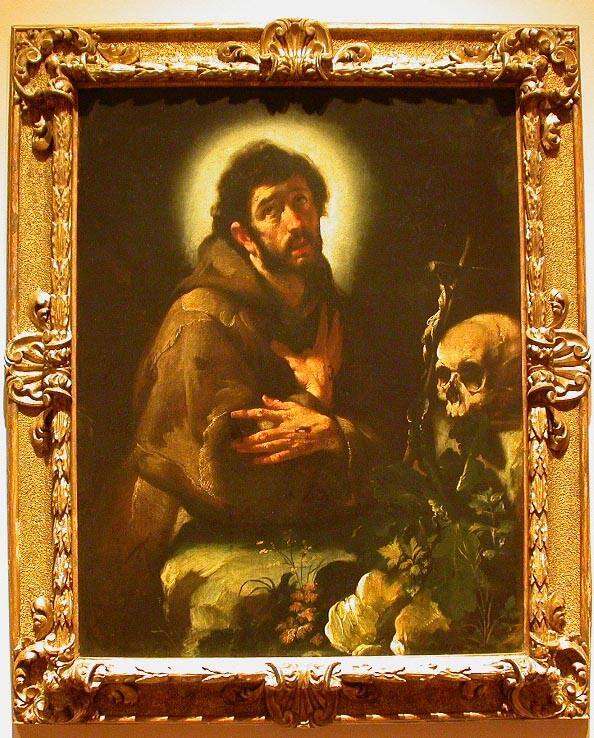

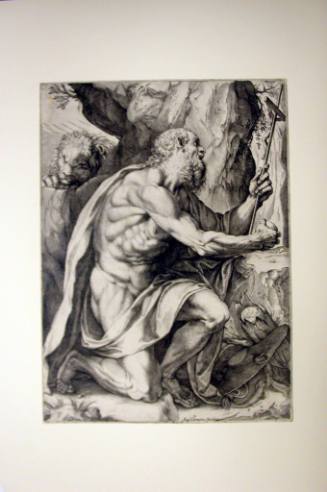

He studied briefly with the painter and antiquarian Cesare Corte (1550–1613/14) (Soprani) and was then sent by his mother to train with the Sienese painter Pietro Sorri (1556–1621), who was in Genoa from 1595 to 1597. In 1598 he became a Capuchin monk and entered the monastery at S Barnaba, Genoa. Here he may have made devotional paintings of saints, especially St Francis; such works as St Francis in Prayer (Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco), painted in dark, almost monochromatic browns, perhaps date from this time. The background is shadowy and the saint, in the foreground plane, makes a strong and direct emotional appeal. In 1610 Strozzi was granted permission to leave the monastery to support his ailing widowed mother and unmarried sister by his work as a painter. His art drew its inspiration from the rich variety of styles then flourishing in Genoa. He absorbed the Tuscan Mannerist style through his teacher, Sorri, through Tuscan artists who worked in Genoa—among them Ventura Salimbeni (in Genoa c. 1610) and Aurelio Lomi (1556–1622; in Genoa 1597–1604)—and through Giovanni Battista Paggi, who returned to Genoa from Florence in 1600. Further models were provided in Francesco Vanni’s Last Communion of St Mary Magdalene for S Maria Assunta di Carignano, Genoa, painted shortly after 1600, and Federico Barocci’s Crucifixion (1595; Genoa Cathedral), with its vivid, shot colours, which was brought to the city in 1596. Of equal importance was Strozzi’s contact with Milanese painting so that it is often difficult to distinguish the influence of Tuscan Mannerism from that of Lombard painters. He was indebted to Cerano and Morazzone, whose art was well known in Genoa, and to Giulio Cesare Procaccini, who arrived in Genoa in 1618. From Tuscan Mannerists he borrowed elegant and rhythmic poses and an acid and vibrant palette; from Morazzone, and perhaps from Paggi, he learnt the use of brown varnish to deepen the shadows and enhance and soften the areas of light, thus creating the sense of solid figures surrounded by light and air. Cerano inspired his broad, broken brushwork, executed with a loaded brush.

The Pietà (Genoa, Mus. Accad. Ligustica B.A.), one of the earliest works from the period after he had left the monastery, displays Mannerist traits in the sinuous and elongated figures, the inclined heads, the tapering fingers and the abstract patterns of the ample drapery. The brushstrokes are thick and broken, the colours a strange blend, with yellows placed next to blues, greens to purples and oranges to amaranth. The sweetly elegant St Catherine (Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum), bathed in delicately coloured light and echoing the figures and facial types of Procaccini, is from the same period.

Around 1620 Strozzi moved towards a more lively naturalism. In this he was influenced by Caravaggio, whose style of painting was introduced to Genoa both by Domenico Fiasella, who returned there in 1617–18, and by followers of Caravaggio who visited the city, including Orazio Gentileschi, Orazio Borgianni, Angelo Caroselli and Bartolomeo Cavarozzi. Moreover, through Marcantonio Doria (ii), a patron of Strozzi, works by Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, Jusepe de Ribera, and Caravaggio himself reached Genoa (Alfonso). It has been suggested that Strozzi may even have encountered Caravaggio’s work directly on a visit to Rome c. 1615 (Botto and Marcenaro). The Calling of St Matthew (c. 1617; Worcester, MA, A. Mus.) is closest in style to Caravaggio, resembling the latter’s own painting of this subject (1599–1602; Rome, S Luigi dei Francesi; see fig.). Yet there remains a Mannerist artificiality in the elaborate play of light sources. The figures are crowded into a more confined space than in Caravaggio’s work, and poses and gestures are mannered; colour remains more important than chiaroscuro. Likewise, in the Adoration of the Shepherds (1615–20; Baltimore, MD, Walters A.G.), the theatrical quality of the lighting contrasts with the striking realism of the still-life elements and figures.

In this period Strozzi also embarked on a career as a fresco painter though little of this work has survived. Best preserved are three frescoes: Marcus Curtius Leaping into the Abyss, Horatius Cocles Defending the Bridge and Dido and Aeneas in the Cave (all Sampierdarena, Villa Centurione-Carpaneto), where the marked influence of Sienese Mannerism and of Barocci suggests a date around 1617, contemporary with the St Matthew. These works show that Strozzi was by inclination an easel painter; they share none of his Genoese contemporaries’ interest in space and illusionism. The Marcus Curtius Leaping into the Abyss is painted as though it were an easel painting—and is framed by decorative motifs, derived from an older Genoese tradition, which are not intended to have a space-creating function. Only a fragment remains of the frescoes he made for the choir of S Domenico, Genoa, showing the head of John the Baptist (Genoa, Mus. Accad. Ligustica B.A.). A sketch for a fresco of Paradise (Genoa, Mus. Accad. Ligustica B.A.) reveals Mannerist traits.

In the 1620s Strozzi broke more decisively with the Mannerist elements in his art and began to develop warmer colours and a more robust style of painting. To the influence of Caravaggio was added that of Rubens and of the colony of Flemish artists resident in Genoa. In Strozzi’s St Lawrence Distributing the Riches of the Church (early 1620s; St Louis, MO, A. Mus.) the space is clear and lucid, light and shade are no longer arbitrary, but define the forms, and the impasto is yet thicker. In this period he created some of his most famous and much copied works, such as the Esau and Jacob (version Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco) and the Supper at Emmaus (version Grenoble, Mus. Grenoble). His serene and balanced religious pictures are less provocatively naturalistic than those of Caravaggio; naturalism merely gave him the means of developing beyond his Late Mannerist tendencies. Flemish genre scenes inspired a group of works that include the magnificent Cook (c. 1625; Genoa, Gal. Pal. Rosso), based on Pieter Aertsen’s Cook (1559; Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco) and the vital, boisterous Pifferari (Genoa, ex-priv. col. Basevi; see Mortari, 1966, fig.), which exists in several replicas. Strozzi’s use of coloured shadows is indebted to Rubens, although, as demonstrated in the Cook, he covered a reddish-brown ground with light brushstrokes in paler colours rather than adopting Rubens’s practice of allowing a light-coloured ground to occasionally emerge on to the surface.

In 1629 Strozzi painted his earliest dated work, an altarpiece, the Virgin and Child with St Lawrence and the Young St John the Baptist for the church of the Sordomuti in Genoa (in situ). Here the figures are set on a terrace, and a balustrade against a cloud-streaked sky creates a new sense of open space. At this date Strozzi began to respond to Venetian light and colour. He would have seen many works by Venetian painters in Genoese private collections.

2. Venice, 1630–44.

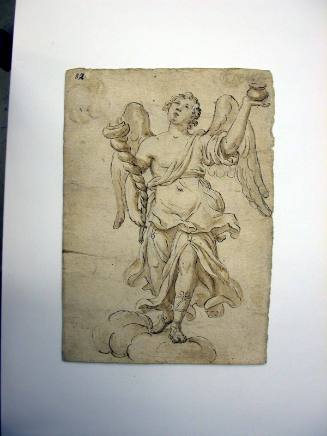

By 1630 Strozzi’s mother was dead and his sister had married, so he no longer had cause to remain outside his monastic order. Yet he was reluctant to obey a call to return to the monastery and moved to Venice in late 1630 or early 1631, in which city he was nicknamed ‘il prete Genovese’. There are some dated works from the Venetian period. Among the earliest is a portrait of Cardinal Federico Correr (Venice, Correr), probably painted to commemorate the sitter’s election as Patriarch of Venice in 1630. Later works include portraits of many other local nobles, suggesting Strozzi’s high standing in Venice. His interest in Venetian painting intensified in this period. A deeper knowledge of Veronese’s art inspired him to adopt a bolder and more luminous palette. For his Allegory of Sculpture (1635; Venice, Bib. N. Marciana) he borrowed from Veronese the pose of the figure, the di sotto in sù viewpoint and the luminous atmospheric background. Yet the influence of Rubens remained strong; the Minerva (mid-1630s; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) unites the robust forms and brilliant colour of Rubens with the warm atmosphere of Venetian art. A drawing for this figure, in black and red chalk on buff-pink paper (Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.), is one of very few full-scale preparatory drawings by Strozzi to have survived.

In Strozzi’s St Sebastian Tended by St Irene (late 1630s; Venice, S Benedetto) the composition is open, with monumental figures surrounded by light and air. A luminous sky is visible between the branches of the tree to which the saint is bound. There is neither drama nor tragedy; deeply considered poses and gestures convey meaning. With his St Lawrence Distributing the Riches of the Church (Venice, S Nicolo dei Tolentini), his masterpiece of the later 1630s, he returned to a favourite theme, abandoning the half-length figures of earlier versions for full-length figures whose monumentality is conveyed by using an upward-looking viewpoint. The beggars have a robust Flemish vitality but the theatrical staging, and light and colour, are Venetian.

Some of Strozzi’s Venetian works, such as the Three Fates (1635–40; Milan, Bonomi priv. col.; see Mortari, 1966, pl. 331) are crudely realistic, and suggest the influence of painters from northern Europe. His latest works, such as the David (after 1640; Rotterdam, Boymans–van Beuningen) and the Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well (Dresden, Gemaldegal. Alte Meister), are increasingly luminous and sketchy. His Lute Player (after 1640; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.) is in a poetic mode clearly influenced by the work of Giorgione. Of his few surviving drawings, such examples as the Head of an Old Woman (mid-1630s; Rotterdam, Boymans–van Beuningen) are studies of light and shade in black chalk, with hatching, and often cross-hatching, used to define areas of shadow.

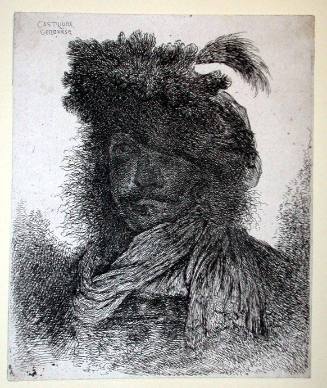

On his death Strozzi left many pupils and followers. In Genoa he had a considerable impact on painting in the first half of the 17th century. He must have had a workshop, given the volume of his output and the repeated versions bearing his signature, as well as faithful copies in which the uneven quality suggests his intervention. Antonio Travi and Giovanni Andrea de’ Ferrari were his pupils but his true heirs were Gioacchino Assereto, Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione and Valerio Castello (see Castello (ii), (2)). In Venice his paintings inspired new life in the work of Carlo Saraceni, Domenico Fetti and Johann Liss. He influenced the paintings of Francesco Maffei, Girolamo Forabosco and certain works by Pietro Muttoni (1605–78). The early Venetian works of Sebastiano Mazzoni also owe much to Strozzi.

Chiara Krawietz. "Strozzi, Bernardo." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081874 (accessed April 12, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665