Hendrick Terbrugghen

Dutch, 1588 - 1629

Dutch painter and draughtsman. He was, with Gerrit van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen, one of the leading painters in the group of artists active in Utrecht in the 1620s who came to be known as the Utrecht Caravaggisti, since they adapted Caravaggio’s subject-matter and style to suit the Dutch taste for religious and secular paintings. Ter Brugghen was an important innovator for later Dutch 17th-century genre painting; his recognition as an unorthodox, but significant influence on the work of Johannes Vermeer and others is a relatively recent, 20th-century phenomenon.

1. Life and work.

(i) Background and training in The Hague and Utrecht, before c. 1605.

His grandfather, Egbert ter Brugghen (d 1583), was a Catholic priest who came from a prominent Utrecht–Overijssel family and who, in the last years of his life, served as the pastor of the Utrecht village of Ter Aa. Hendrick’s father, Jan Egbertz. ter Brugghen (c. 1561–?1626), though illegitimate, had a successful career as a civil servant: in 1581 he was appointed secretary to the court of Utrecht by Prince William of Orange and in 1586 he was first bailiff ordinaris of the chamber of the Provincial Council of Holland at The Hague. Hendrick’s date of birth is derived from the biographical inscription placed on the four frames of his series of the Four Evangelists (1621; Deventer, Stadhuis) by Richard ter Brugghen (c. 1618–1708/10), the only survivor of his eight children, who presented the canvases to the city of Deventer in 1707.

Hendrick was probably born in The Hague rather than Utrecht, as previously believed, since his father appears regularly in The Hague documents from 1585 to 1602. The young Hendrick probably also received his earliest education in The Hague. However, between 1602—when Hendrick would have been 13 or 14—and 1613, Jan ter Brugghen is again intermittently recorded in Utrecht, where Hendrick studied with Abraham Bloemaert—an indisputable fact supported by such 17th-century sources as Sandrart (1675), who had known the painter while a student in Gerrit van Honthorst’s Utrecht workshop c. 1625–8. (Bloemaert was also van Honthorst’s teacher.) What is unknown, however, is whether ter Brugghen first studied with some as yet unidentified master in The Hague before finishing his training with Bloemaert, or whether, like Rembrandt, he first received a conventional Latin education in preparation for a career as a civil servant. The matter is of some importance since it raises the possibility that ter Brugghen was a relatively late or slow starter, which might account for the problems involved in identifying his early work. Exactly how long Hendrick spent in Bloemaert’s workshop also remains unknown, but it is unlikely that his training began before 1602, when his father returned to Utrecht.

(ii) Italy, c. 1605–14.

During the summer of 1614 ter Brugghen, along with another Utrecht artist, Thijman van Galen (b 1590), was in Milan preparing for his return journey through St Gotthard’s Pass to the northern Netherlands. In a Utrecht legal deposition dated 1 April 1615, concerning a third Utrecht artist they had met on their return journey, Michiel van der Zande (c. 1583–before 1643), and his young servant, the future landscape painter Frans van Knibbergen (c. 1597–1665 or after), ter Brugghen and van Galen testified that they ‘had spent some years in Italy exercising their art’. The ambiguous Dutch term ettelicke (‘some’) used by ter Brugghen in the document usually implies an amount less than ten, thus suggesting that the presently accepted sojourn of ten years should be modified. While ter Brugghen could have spent as little as two or three years in Bloemaert’s studio before travelling to Italy c. 1604 or 1605, he probably left in the spring or summer of 1605—at the age of 16 or 17. He must have arrived in Rome by 1606, if Cornelis de Bie’s statement (1708) that he knew Rubens in that city is correct. If so, then ter Brugghen would have been the only member of the Utrecht Caravaggisti to have arrived in Rome while Caravaggio was still active there. Unfortunately, unlike his compatriots van Honthorst and Dirck van Baburen, there is no trace of ter Brugghen’s long stay in Italy—either in the form of a document or a work of art. It may be that his youthful style in Italy was sufficiently different from that which he developed after his return to the northern Netherlands to remain unrecognized.

(iii) Early Utrecht period, 1615–24.

In 1616 ter Brugghen entered the Utrecht Guild of St Luke and on 15 October of the same year he married Jacomijna Verbeeck (d 1634), the stepdaughter of his elder brother Jan Jansz. ter Brugghen, a Utrecht innkeeper. Even though Utrecht was a predominantly Catholic centre, the marriage ceremony took place in a Reformed Church, and since the children of this marriage were also baptized in the Reformed Church, it seems likely that the artist was himself Protestant rather than Catholic, as was previously thought. This raises important questions about the subject-matter and function of several of the artist’s most important works.

Ter Brugghen’s earliest known work, a life-size Supper at Emmaus (1616; Toledo, OH, Mus. A.), reveals that he had studied Caravaggio’s painting of the same theme (between 1596 and 1602; London, N.G.; see fig.) as well as another version by an anonymous north Italian artist (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.). Thus ter Brugghen turned not only to the works of Caravaggio himself but also to his north Italian sources and followers. Indeed, various works by members of the Bassano family and their workshop exerted an ongoing influence on ter Brugghen. The only other known dated painting by ter Brugghen from this early Utrecht phase of his development is the signed and dated Adoration of the Magi (1619; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), an important picture that betrays the influence of such followers of Caravaggio as Carlo Saraceni.

Several undated works by ter Brugghen can be assigned on stylistic grounds to the period before 1620, including the strikingly coloured, full-length version of the Calling of St Matthew (Le Havre, Mus. B.-A.), which ter Brugghen repeated in a more compact, half-length composition with a modified colour scheme (1621; Utrecht, Cent. Mus.). These two paintings and other early works are remarkable for their utilization of early 16th-century Netherlandish physiognomic types and still-life details intermixed with formal elements drawn from Caravaggio’s famous painting of the same subject in S Luigi dei Francesi, Rome (see fig.). In another apparent attempt to modify the Italianate elements of his style and thus make his work more acceptable to conservative Utrecht tastes, ter Brugghen, in the unusual Christ Crowned with Thorns (1620; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst), again tempered his personal form of Caravaggism with native poses and physiognomic features, this time drawn from the prints of Lucas van Leyden.

These traditional Netherlandish insertions largely ended with the return of van Honthorst and van Baburen from Italy during 1620. Together with ter Brugghen, these artists quickly succeeded in transforming the nature of Utrecht art during the following year. Indeed, at the beginning of 1621 ter Brugghen was still producing works such as the Four Evangelists (Deventer, Stadhuis), which has the same unusual mixture of Caravaggesque elements and traditional 16th-century Netherlandish still-life details. Later that same year, however, when he came into contact with the latest Italian Caravaggesque ideas brought back by van Baburen (with whom he probably shared a workshop from c. 1621 until van Baburen’s death early in 1624), ter Brugghen executed two lovely pendant versions of The Flute-player (both Kassel, Schloss Wilhelmshöhe), one depicted in a pastoral manner, wearing an all’antica, toga-like costume, and the other more theatrically dressed in a flamboyant outfit of the type usually described as ‘Burgundian’. These influential works are dependent on the Italian Caravaggesque elements developed by Bartolomeo Manfredi in Rome after ter Brugghen had departed in 1614; they can thus only have been introduced into Utrecht by van Baburen and van Honthorst. Van Baburen, in particular, was an important iconographic and artistic innovator in Utrecht, who provided ter Brugghen and other members of the Utrecht Caravaggisti with both new themes and new approaches to old themes; these were quickly taken up and transformed by ter Brugghen.

Despite their varied sources, the two versions of The Flute-player do possess the hallmarks of ter Brugghen’s style and personality: a subtle utilization of unusual colour harmonies, lively brushwork and paint surfaces, complex and varied drapery folds and, especially, a certain reticence in the compositional structure, which stands in marked contrast to the more extrovert types and arrangements frequently found in the pictures of van Honthorst and van Baburen. From 1621 ter Brugghen often employed a cool, crisp light source and a sense of form derived as much from the direct observation of the movement of light across surfaces as from such prime Italian followers of Caravaggio as Orazio Gentileschi. A closely similar light quality is found in van Baburen’s work, implying that both painters developed this characteristic aspect of their style from their study of Gentileschi in Italy. Interestingly, ter Brugghen only rarely deployed the kind of artificial illumination popularized by van Honthorst.

In an effort to account for the new and up-to-date Italianate elements in the two versions of The Flute-player as well as in others, it has been suggested that ter Brugghen made a second journey to Italy (Schuckman). However, the only time when the artist’s presence in Utrecht is not documented is between the summer of 1619 and the summer of 1621, hardly long enough for him to accomplish the full agenda of stylistic contacts and influences that some scholars would like to assign to this unconfirmed second sojourn in Italy. Furthermore, since there are more dated works by ter Brugghen from 1621 than almost any other year, it is unlikely that he could have spent any part of that critical year travelling.

After 1621 ter Brugghen produced numerous single-figure genre pictures of the type usually associated with Utrecht: lute-players, musicians, drinkers etc. These are usually rendered with a sensitivity beyond the reach of his Utrecht colleagues (who had originated these themes) and with compositional reticence that is frequently in sharp contrast to the type of activities depicted: the theatrical Singing Lute-player (c. 1623; Algiers, Mus. N. B.-A.), for example, is depicted in lost profile with his back turned towards the viewer. In the pendant canvases (both 1623) of a Boy Lighting a Pipe (Erlau, Lyzeum) and a Boy Holding a Glass (Raleigh, NC Mus. A.), ter Brugghen introduced the northern Caravaggesque device of internal artificial illumination associated in Utrecht with van Honthorst. Characteristically, ter Brugghen imbued these apparently simple genre depictions with ideas developed from popular Dutch beliefs concerning the complementary effects of smoking (hot and dry) and drinking (hot and moist), adding an unusually sensitive investigation of the movement of candlelight across the complex arrangement of fabric and form. Moreover, especially in the better-preserved Boy Lighting a Pipe, one of the earliest paintings to focus exclusively on the new activity of tobacco smoking, he introduced idiosyncratic colour relationships quite different from those found in his works from before 1621.

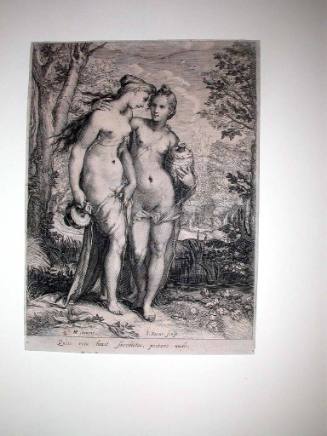

About the same time ter Brugghen took up the traditional northern theme of the Unequal Lovers (c. 1623; New York, priv. col., see 1986–7 exh. cat., no. 14) in an unusually compact, half-length composition that suggests that he had early 16th-century northern moralizing pictures in mind. Indeed, specific details of the depiction of the old man—including his costume—indicate that ter Brugghen had read the appropriate passages in Erasmus’s famous In Praise of Folly (1511). Although no longer indulging in the same kind of borrowing of archaic motifs as before, ter Brugghen clearly continued to look to his northern artistic antecedents more than his Utrecht contemporaries. At the same time, the picture is also strongly dependent on van Baburen for various stylistic and thematic elements; the two artists obviously had an unusually close working relationship throughout the early 1620s.

In the lovely Liberation of St Peter (1624; The Hague, Mauritshuis), with colour and compositional patterns that seem to develop out of the Boy Lighting a Pipe, ter Brugghen returned to religious subject-matter and introduced new physical types for both the angel and the saint, types that continued to recur in his works until his death. The new type for the angel, with its declamatory gesture, was probably at least partly indebted to van Baburen, who had used a similar pose for an Annunciation (untraced; copy by Jan Janssens, Ghent, Mus. B.-A.).

(iv) Mature Utrecht period, 1625 and after.

Hendrick ter Brugghen: The Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint…About 1625 ter Brugghen entered into a new and more mature phase of his artistic development with two of his most important and innovative paintings, the Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John (New York, Met.; see fig.) and St Sebastian Tended by Women (Oberlin, OH, Allen Mem. A. Mus.). Both have monumental compositions and the sort of steep perspective traditionally associated with altarpieces for Catholic churches, although it cannot be proven that either ever served such a religious function. Most striking is the Crucifixion, an unusually expressive, but obviously 17th-century recreation of a 15th-century northern Netherlandish work of art. The low horizon line, the simple iconic composition, the star-studded sky and the rendering of the body of Christ, as well as other details, suggest that ter Brugghen—or more likely his patron—wanted an old-fashioned picture that could pass, at least at first glance, for a 15th-century altarpiece. The St Sebastian, on the other hand, is a modern Caravaggesque work that clearly reflects elements of Caravaggio’s Entombment (Rome, Pin. Vaticana) as well as his Incredulity of Thomas (Potsdam, Neues Pal.); notable in all these works is the use of powerful descending diagonals and the careful positioning of the three heads. Although the new theme of St Sebastian Tended by Women owes something to van Baburen’s innovative painting of the same subject (Hamburg, Ksthalle), ter Brugghen’s version is one of those rare pictures that completely transcends its formal and iconographic sources, a work whose unusually high level of artistic and expressive perfection was rarely matched in Dutch 17th-century religious painting before the mature works of Rembrandt.

One of the most unusual of the extremely varied group of history and genre pictures that ter Brugghen created during the second half of the 1620s is the Sleeping Mars (c. 1625 or 1626; Utrecht, Cent. Mus.). The picture was enormously popular during the 17th century; around 1650 and even later it was the subject of several didactic poems, although the theme was explained entirely in terms of Dutch political events of that later period. In fact, ter Brugghen’s picture was executed a few years after the Twelve Years’ Truce between Spain and the revolting northern provinces of the Spanish Netherlands had ended in 1621 and should thus be understood as a plea for peace after the resumption of hostilities. Medallions and tokens with similar images of the sleeping god of war had been struck to commemorate the signing of the truce in Utrecht in 1609, and the artist and his patron would certainly have been aware of the symbolic message of these and other related works.

Ter Brugghen’s most beautiful and successful genre paintings, also among his mature works, include the candlelit Musical Company (c. 1627; London, N.G.). The composition’s unusual formality, in contrast to the everyday activities depicted, along with other details suggest that ter Brugghen was inspired by a musical allegory similar to that found in Caravaggio’s Musicians (New York, Met.). The choice of the three essential categories of music-making (voice, winds and strings) and the elegantly placed wine and grapes—symbolic of the Bacchic origins of music—support such an interpretation.

In 1627 the great Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens visited Utrecht and stayed in the inn owned by ter Brugghen’s brother (lending some credence to de Bie’s report that the two artists had met in Rome). He apparently praised the work of ter Brugghen above that of all the other Utrecht artists. This praise would not be difficult to understand even if Rubens had seen only ter Brugghen’s Musical Company. Rubens’s visit may be at least partly responsible for the renewed use of Italian elements in ter Brugghen’s work at this time, as can be seen, for example, in the candlelit Jacob and Esau (c. 1627; Madrid, Col. Thyssen-Bornemisza), which, although formally structured like the Musical Group, is also strongly indebted to elements borrowed from the Bassano workshop, as is his second version of the same theme (c. 1627; Berlin, Bodemus.). The rich and varied surface of the Musical Company and other late pictures by ter Brugghen, for instance Melancholy (Toronto, A.G. Ont.), make it clear that the master’s renewed interest in north Italian painting was not limited to composition alone. The layers of fluid, semi-transparent brushwork, unusually subtle colour harmonies and artificial illumination all combine to produce some of the artist’s most engaging works. Furthermore, single-figure compositions such as the candlelit Old Man Writing (Northampton, MA, Smith Coll. Mus. A.), with its close investigation of artificial light effects, show that ter Brugghen was still influenced by early 16th-century Netherlandish sources, such as Lucas van Leyden’s prints and early Leiden school painting, without resorting to the more obvious stylistic archaisms found in his work before 1621.

In stark contrast to the various late candlelit depictions is another group of late paintings, also from 1627 onwards, such as the Allegory of Taste (1627; Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.), which introduce a renewed interest in cool, bright daylight. Although the colour is in some ways indebted to early works such as The Flute-player pendants, it also benefits from the master’s ongoing investigation of artificially lit surfaces and forms. As ter Brugghen approached the age of 40, he entered a new and more mature phase of his development, which features the cool and pale flesh tones seen in the Allegory of Taste and in The Singer (1628; Basle, Kstmus.). Interestingly, it is this lesser-known late phase of his activity as a painter that seems to anticipate aspects of Vermeer’s style even more than the better-known works of c. 1621 usually cited.

During 1628 this new phase manifests itself in the use of bright, but subtle colour harmonies in, for example, the signed and dated Lute-player and Singing Girl (1628; Paris, Louvre), as well as in the pendants of ancient philosophers, the Laughing Democritus and the Weeping Heraclitus (both 1628; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). The Democritus especially, with its beautifully rendered cool yellow highlights on the velveteen drapery, reflects the new and innovative direction of the master’s formal and colouristic interests during this late stage in his career.

During the last two years of ter Brugghen’s life, with works such as the Annunciation (1629; Diest, Stedel. Mus.), the artist continuously experimented with increasingly rich and varied paint surfaces, complex arrangements of drapery folds, the growing use of richly patterned oriental rugs and fabrics and an unusually subtle study of the movement of light across form—all qualities later present in the works of Vermeer. Several of ter Brugghen’s late works, for example the painting of Jacob, Laban and Leah (Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Mus.), also include exceptionally sensitive investigations of still-life elements. Their paint surfaces are also more complex, due to the use of increasingly loose and fluid brushstrokes, which frequently overlay more studied and carefully applied areas as, for example, in Melancholy and The Singer, suggesting that ter Brugghen’s premature death, at the age of only 41, may have cut short the most innovative stage of his artistic development.

2. Working methods and technique.

The recurrence of figures, poses, facial types and motifs in works dated four and five years apart would seem to indicate that drawings played an important role in the artist’s working procedures. A good example of such a repetition is the figure of the angel that appeared first in the Liberation of St Peter of 1624. Ter Brugghen later used a closely related, though full-length figure of the angel for two other paintings, both dated 1629: the Annunciation (Diest) and an expressively composed second version of the Liberation of St Peter (Schwerin, Staatl. Mus.). Furthermore, a similar, half-length angel also appears in the much repeated King David with Angels (1628; Warsaw, N. Mus.), which includes a facial type for King David that resembles that of St Peter from the picture of 1624.

Unfortunately, only three drawings by ter Brugghen have survived, all of which are complete compositions (e.g. Laughing Democritus, Rouen, Mus. B.-A.) rather than studies for individual figures or heads. Nevertheless, the pattern of repetition in his paintings does seem to support a method of working similar to that utilized by his teacher, Abraham Bloemaert. Thus, despite the obviously Caravaggesque components of his style, ter Brugghen’s working method appears to be rooted in Utrecht Late Mannerist workshop procedures more than that of either the younger van Baburen or van Honthorst, despite the fact that the latter had also been a student of Bloemaert.

Leonard J. Slatkes. "Brugghen, Hendrick ter." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T011726 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Flemish, 1575 - 1632