Image Not Available

for George Inness, Sr.

George Inness, Sr.

American, 1825 - 1894

(not assigned)Eagleswood, New Jersey, USA

SchoolHudson River School

Biography(b Newburgh, NY, 1 May 1825; d Bridge of Allan, Central Scotland, 3 Aug 1894). American painter. He grew up in Newark, NJ, and New York City, and received his first artistic training with John Jesse Barker ( fl 1815-56), an itinerant artist claiming to be a student of Thomas Sully. Between 1841 and 1843 Inness was apprenticed to the engravers Sherman & Smith in New York. More significant was his study in 1843 with Régis-François Gignoux, a student of Paul Delaroche and a recent immigrant from France, whose landscapes were delicate and sweet. Though Gignoux seems to have had little influence on the development of Inness's style, the Frenchman did provide him with a knowledge of European masters. Inness's early attraction to the Old Masters, especially to Claude Lorrain, is evident in his landscapes of the 1840s, and it prompted him to visit Italy in 1851-2. His Bit of the Roman Aqueduct (c. 1852; Atlanta, GA, High Mus. A.) is especially derivative of Claude in its classical composition and descriptive details.

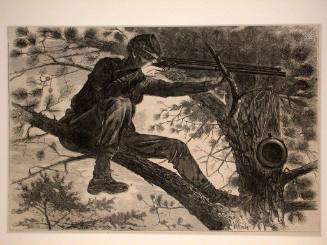

In 1853 Inness returned to Europe for two years. In France he was impressed by the Barbizon school of landscape painting which had a decisive influence on his art. The Barbizon style became pronounced in his work after 1860 when he moved from New York, home to the dominant Hudson River school of landscape painting, to Medfield, MA, a village where he could work in isolation. Pictures such as Clearing up (1860; Springfield, MA, Smith A. Mus.; see fig.) have the sketch-like brushwork, loosely structured composition and rustic themes associated with the Barbizon work of Théodore Rousseau.

Inness travelled to Europe a third time in 1870, settling in Rome, where he painted The Monk (1873; Andover, MA, Phillips Acad., Addison Gal.). With its ambiguous spaces, enigmatic theme and brooding colours enlivened with chromatic flourishes, it is the most avant-garde American painting of the 1870s. On his return to America in 1875, Inness worked for a while in New Hampshire, where he painted such pictures as Saco Ford: Conway Meadows (1876; South Hadley, MA, Mount Holyoke Coll. A. Mus.), which shows a heightened confidence in the use of swirling, textured brushwork and a temporary concern for the majesty of open spaces.

Beginning in the late 1870s Inness turned to the thoughtful, personal, non-topographic landscapes that are the trademark of his late style. In many respects these landscapes were the result of his religious beliefs. As early as the mid-1860s, when he was living at Eagleswood, NJ, the site of the Raritan Bay Union utopian community, Inness began to study spiritualism. Spurred by Marcus Spring, leader of the Eagleswood community, and by the painter William Page, he became a disciple of the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). Believing that all material objects were spiritually charged and that the earthly realm was continuous with the heavenly, Inness arrived in the late 1870s and 1880s, after years of effort, at a uniquely spiritual imagery. Though still derived from Barbizon painting, Inness's late work is an effort to convert Swedenborgianism into art. Travelling between Montclair, NJ, his permanent home after 1878, and seasonal retreats in California, Florida and Nantucket, MA, where he went to improve his chronically poor health, he painted highly moving, personal pictures. In Niagara Falls (1893; Washington, DC, Hirshhorn) he depicted the Falls dissolved in mists of iridescent colour, in contrast to the highly representational Hudson River style in which it had traditionally been painted, for instance by Frederic Church (1857; Washington, DC, Corcoran Gal. A.). Instead of conveying Church's image of power, Inness's Niagara Falls expresses a brooding inner passion through heavy paint surfaces and dematerialized forms. In Home of the Heron (1893; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) Inness constructed a twilight world of hazy forms cast halfway between substance and nothingness. Space and detail were virtually eliminated in favour of a flat and indistinct landscape of softly vibrating colours and gauzy paint surfaces. Though there is nothing in Swedenborg's writings to account for Inness's late imagery in a specifically iconographic way, pictures like this are redolent of the 'correspondence' Swedenborg claimed existed between the material and the spiritual worlds.

Inness's early works received mixed critical reviews. In the 1840s and 1850s he was often criticized for not adhering to the prevailing taste for the Hudson River school. Instead of imitating nature, the critics claimed, Inness was imitating art. Though Hudson River painters such as Asher B. Durand were equally influenced by Claude, in the critics' eyes Inness made the act of imagination unacceptably overt by stressing broad handling of paint, eccentric colours and palpable atmosphere. Nonetheless, Inness's early pictures were promoted by George Ward Nichols (1831-85), a devotee of French art and the owner of the Crayon Gallery in New York. Inness's early patrons included Ogden Haggerty, who financed his first trip to Europe, and the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (1813-87). The critical response to Inness's art improved greatly during the 1880s and 1890s, though the American Pre-Raphaelites, led by the critic Clarence Cook, condemned his lack of interest in replicating nature. In his later years Inness attracted the attention of Thomas B. Clarke, the leading collector of American art, who purchased works by Inness. (Source: PAUL J. STAITI, "George Inness," The Grove Dictionary of Art Online (Oxford University Press, Accessed August 4, 2004),

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- male

- Caucasian-American