George Romney

English, 1734 - 1802

English painter. He is generally ranked third in the hierarchy of 18th-century society portrait painters, after Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. His art is often repetitive and monotonous, yet at its best is characterized by great refinement, sensitivity of feeling, elegance of design and beauty of colour. As a society painter he typified late 18th-century English artists who, compelled by the conditions of patronage to spend their time in producing portraits, could only aspire to imaginative and ideal painting.

1. Early years and Grand Tour.

Son of a cabinet-maker, Romney joined his father’s business after leaving school at the age of ten or eleven. In March 1755 he formally embarked on a career as an artist by signing indentures apprenticing him to the itinerant painter Christopher Steele, with whom he travelled as far as York and Lancaster. Two years later the indentures were cancelled, and Romney set up a portrait practice in Kendal, charging two guineas for a three-quarter-length portrait and six for a full-length on a kit-cat canvas. In addition he executed a number of original subject pictures and copies after prints, 20 of which were sold for £100 in a lottery in the spring of 1762. Very few drawings or subject pictures survive from this early period, but his portraits, such as Jacob Morland (1763; London, Tate), are akin to Steele’s neat style.

In March 1762 Romney went to London, leaving his wife and family in Kendal. There he quickly established himself as a painter of historical subjects and portraits. His first exhibited painting was a modern historical subject, the Death of General Wolfe (untraced, see Ward and Roberts, ii, p. 200), shown at the Society of Arts in 1763. Initially judged second, this painting was demoted in favour of John Hamilton Mortimer’s Edward the Confessor Stripping his Mother of her Effects (San Marion, CA, Huntington Lib. & A. G.), but was awarded a ‘bounty’, which brought him some publicity in the Gentleman’s Magazine and elsewhere. He worked in the cast gallery, which had been opened by Charles, 3rd Duke of Richmond, in 1758. At the end of August 1764 he set out for Paris with his friend Thomas Greene, a solicitor, whose diary describes the palaces, churches and art collections they visited during their six-week stay. Romney’s response to contemporary French art was negative: he wrote to his brother that ‘the degeneracy of taste runs through everything…. The ridiculous and fantastical are the only points they seem to aim at. …but those of the time of Louis the fourteenth are very great’ (quoted in J. Romney, p. 50).

Romney’s portraits of 1764–73 demonstrate the increasingly sophisticated conventions that evolved in the years following the establishment of the Royal Academy in London. His ambitious Leigh Family (Melbourne, N.G. Victoria), exhibited at the Free Society of Artists in 1768, for example, combines elements of both the conversation piece and the Grand Style popularized by Reynolds. A fine example of Romney’s early Neo-classical style is Mrs Verelst (1771–2; priv. col., see Ward and Roberts, i, p. 22), in which he adapted the pose of the Mattei Ceres (Rome, Vatican, Gal. Candelabri), famed for the beauty of its draperies, to the demands of fashionable portraiture. It is characterized by an elongated linearity, with an emphasis on silhouette and pure and restrained colour. He continued to participate in exhibitions of the Free Society of Artists until 1770, when he first showed with the Society of Artists. He was not asked to join the Royal Academy, and his works were not exhibited there in his lifetime.

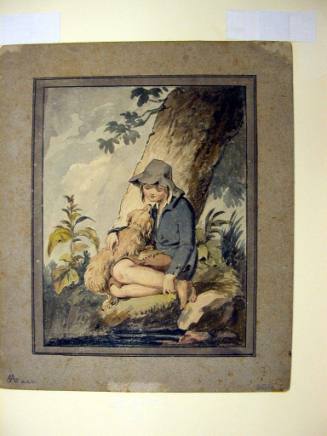

By the mid-18th century a trip to Italy had become an indispensable part of an artist’s education, and on 20 March 1773 Romney abandoned his substantial practice and left for Rome with the miniature painter Ozias Humphry. A diary (New Haven, CT, Yale Cent. Brit. A.) details their trip only as far as Genoa, but enough evidence exists, both documentary and artistic, to call into question the statement that his time in Rome was spent in solitary study. His work shares both formal and thematic affinities with that of Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, Johan Tobias Sergel, Thomas Banks, Nathaniel Marchant, Joseph Wright of Derby and John Browne, who were all in close contact with Henry Fuseli. They developed a highly charged drawing style based on the human figure, characterized by simplified forms, histrionic gesture and broadly applied wash. At the same time Romney made careful studies after the nude, the Antique and the Old Masters, especially Michelangelo and Raphael. He left Rome on 10 January 1775, visiting Florence (where he made copies after Cimabue and Masaccio), Bologna (where he looked at the paintings recommended in Reynolds’s Discourses), Ferrara, Venice and Parma on his return journey, arriving back in England on 1 July 1775. By 25 November he had taken the leasehold on Francis Cotes’s grand house, 24 Cavendish Square, an ambitious undertaking for a man who had to re-establish his career. By the end of 1776, however, he had become a staggering success, according to Humphry (correspondence, London, RA, Hu/2/47). Paintings such as Mrs Carwardine and Child (c. 1775; priv. col., see Waterhouse, pp. 223–4) and The Gower Children (1776–7; Kendal, Abbot Hall A.G.) demonstrate the maturing experience of his Italian trip. In Mrs Carwardine and Child he adapted Raphael’s Madonna della sedia to create an intimate and tender image of motherly love; in The Gower Children a boldness and breadth of composition, ultimately derived from Nicolas Poussin, is married with his graceful and carefree vision of childhood.

2. Studio practice and later career.

George Romney: Lady Elizabeth Hamilton (1753–1797), Countess of Derby, oil…Romney’s sitter books from March 1776 to December 1795 (see Ward and Roberts; 1785 is missing) record some 1500 sitters, many of whom commissioned two or three portraits (see fig.). It is clear that the number of sittings was often more than the three or four that a gentleman’s three-quarter-length portrait would take. Contemporaries described the rapidity of his handling (e.g. Hayley, pp. 323–4; J. Romney, p. 165), and later conservation work has confirmed this. Various pupils and assistants kept a daily record of activities in the studio between October 1786 and April 1796 (London, N.P.G.). The number of sittings per day ranged from three to six or even seven at the height of the season, with one or even two on a Sunday. Romney preferred to paint drapery from a model, but entries in the studio accounts confirm that on occasion he made use of lay figures. The large number of sitters may have been attracted by his prices, which were consistently lower than those charged by Reynolds or Gainsborough. In 1786 he charged 20 guineas for a three-quarter length, while Gainsborough’s price was 30 and Reynolds’s 50 guineas. John Romney stated that in that year Romney painted portraits to the value of 3504 guineas. In 1795 Joseph Farington believed him to be worth £50,000.

In 1775 Romney renewed his friendship with the much younger John Flaxman, and in 1776 he met the poet William Hayley (1745–1820), his future biographer. Hayley befriended a number of artists and writers, including Edward Gibbon, Anna Seward, Joseph Wright of Derby, William Cowper, Flaxman and William Blake, who became the subjects of his effusive and ill-judged literary efforts. His Epistle on Painting (1778) may have promoted Romney’s reputation, but Hayley opposed Jeremiah Meyer’s advice that Romney should exhibit at the Royal Academy, which probably exacerbated Romney’s naturally nervous and moody disposition. During Romney’s yearly visits to Hayley’s house, Eartham, W. Sussex, he was plied with subjects for historical compositions rather than being provided with rest and recuperation.

By 1780 Romney’s portraits, according to Horace Walpole, were ‘in great vogue’ (see Gatty). Work during this period, such as Mrs Musters (1779; London, Kenwood House) or Anne, Lady de la Pole (1786; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), shows his response to youthful beauty and good looks. He was sensitive to the surface qualities of skin, hair and fabric, subordinating character to elegant patterns and delicate feeling. He rendered the gestures of fashionable society with great sensitivity—the tilt of a head, or the set of a mouth, as, for example, in his 16 Eton College portraits, which include Samuel Whitbread and Charles Grey (both in situ). His rapid handling, close to his abbreviated drawing notation, and the use of repeated formulae led to increasing generalization, but no decrease in the number of sitters. As late as 1791 he could produce the refined image of Mrs Lee Acton (San Marino, CA, Huntington A.G.), one of his finest full-lengths, and the nobly introspective portrait of Warren Hastings (1795; London, India Office Lib.).

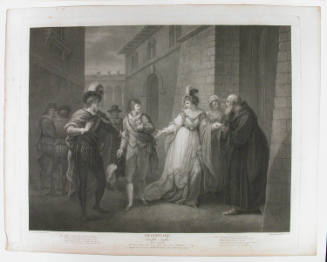

However, Romney was still ambitious to succeed as a history painter, and his diaries record a number of models; the most important of these was Emma Hart, who first visited his studio in 1781. He painted her many times and in many roles (e.g. Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante, London, Tate; Lady Hamilton at the Spinning Wheel, London, Kenwood House). These are the works for which he is most famous, and they were often reproduced as copies. In 1786 Hart was sent to Naples, eventually marrying Sir William Hamilton (i), and Romney lost his source of inspiration. Other friends provided him with literary themes, but it was not until the inception of the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery scheme in 1786 that an opportunity to exhibit imaginative paintings outside the Royal Academy was created. Characteristically, Romney embarked on a huge undertaking, perhaps prompted by rivalry with Reynolds, who in 1785 had received a prestigious commission from Catherine the Great for The Infant Hercules (St Petersburg, Hermitage). Romney twice reduced the number of his sitters (in 1787 and 1788) to concentrate on The Tempest (Rome, G.N. A. Mod.), but, after four years’ work, it was not judged a success.

During the late 1780s Romney’s health had begun to deteriorate. At the end of July 1790, perhaps influenced by revolutionary ideals, he travelled to Paris with Hayley and the Rev. Thomas Carwardine to stay with John Warner, chaplain to Lord Gower, England’s new ambassador there. It was a period when revolutionary aspirations were most intense and their letters report current events and festivities in detail. They met Jean-Baptiste Greuze and Jacques-Louis David, and were particularly impressed by the latter’s Death of Socrates (New York, Met.), Paris and Helen and the Oath of the Horatii (both Paris, Louvre). The contrast between the opportunities for contemporary history painters in Paris and those which existed in London must have been marked. In tune with Romney’s admiration for the pathetic and terrible, a new subject arose out of this trip. The philanthropist John Howard had died in 1790, and it was planned to raise a memorial to him. Typically, Romney set to work on this scheme. About the same time, encouraged by Hayley, who was writing a biography of John Milton, Romney made many drawings on subjects from Milton and considered a Milton series.

The deaths of Gainsborough in 1788 and Reynolds in 1792 seem to have increased Romney’s ambition. Farington reported that had Romney been appointed Portrait Painter to the King he would have exhibited at the Royal Academy. The last decade of Romney’s life was marked by increasing ill-health and depression, which visits from Hamilton’s wife in 1791 dispelled only briefly. He ordered casts after the Antique from Flaxman in Rome (1792) and in a letter to Hayley (12 Dec 1793) mentioned a projected Birth of Man series. His health began to fail, and the number of unfinished portraits began to accumulate. Patrons complained of his slowness in finishing pictures, and he himself wrote that his delight in new ideas for pictures was greater than the profit to be gained by finishing them. By 1796 Romney had virtually retired from business and was largely preoccupied with plans for his new house and studio in Hampstead. According to Farington, however, as late as 1797 Romney as well as Flaxman, John Opie and Thomas Stothard were ‘all on fire’ with schemes for decorating churches. He moved to Hampstead before Christmas 1798, although building work was still incomplete; as a result some of his work was destroyed or stolen. A series of strokes followed and left him virtually unable to paint. He made a visit to the north of England in 1798 (where he worked only in crayon) and returned to his wife in Kendal in 1799, also buying property in Ulverston.

From Farington’s Diary it is clear that Romney was acquainted with numerous artists, but that suspicion and mistrust were felt on all sides. Romney’s success (at times he rivalled Reynolds in popularity) derived from his portrait business but, in Flaxman’s words, ‘his heart and soul were engaged in the pursuit of historical and ideal painting’—aspirations which resulted in thousands of drawings but very few finished pictures.

Romney owned a large number of casts after the Antique, some of which he had ordered from Flaxman while the latter was in Rome in 1792. Banks and Flaxman acquired 14 fine pieces when authorized to bid on behalf of the Royal Academy (sold London, Christie’s, 18 May 1801). Romney’s painting collection was small, but he did own a large collection of engravings after Italian, Dutch and French Old Masters, as well as some after Reynolds. His reputation faded almost immediately after his death. The sales of his paintings made very low figures, and many of his pictures had to be bought in. In the Quarterly Review (Feb 1810) John Hoppner savaged Hayley’s Life, published the previous year; although he found it difficult either to be just or balanced, he judged Romney to have been the inheritor of Kneller’s practice.

Elizabeth Allen. "Romney, George." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T073752 (accessed May 2, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual