Jean Tinguely

Born Fribourg, 22 May 1925; Died Berne, 30 Aug 1991.

Swiss sculptor. He began experimenting with mechanical sculptures in the late 1930s, hanging objects from the ceiling and using a motor to make them rotate. In 1940 he began an apprenticeship as a window-dresser and also attended art classes at the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule, Basle. From 1941 to 1945 he studied there with Julia Ris (b 1904) and discovered the work of Kurt Schwitters, which made a deep impression on him. After World War II he began painting in a Surrealist manner, but he soon abandoned painting to concentrate on sculpture. In 1949 he met Daniel Spoerri. In 1953 they created the ‘Autothéâtre’, a ballet of colours and movable décor, made up of coloured forms in motion. Here there was no difference between actor and spectator, and actions were performed on stage without the participation of actors, the spectator being the same as an actor, much like the later Happening. The same year Tinguely moved to Paris. There he produced his first abstract spatial constructions, which were gradually equipped with moving mechanisms that could be set in motion by the viewer. These early machines, which Tinguely called ‘meta-mechanical’ devices (e.g. Meta-mechanical Automobile Sculpture, 1954) were characterized by their use of movement as a central element in their construction. Some of them took the form of series paraphrasing the idioms of other artists, for example the Meta-Kandinsky series (1955) or the Meta-Malevich reliefs (1954), in which geometric shapes were made to rotate at constant, but different, speeds with the aid of spindles and pulleys against the background of a black wooden panel. In 1955 Tinguely participated in the exhibition of kinetic art, Le Mouvement, at the Galerie Denise René in Paris, and in the late 1950s he produced the Meta-matic painting machines (e.g. Meta-matic no. 17, 1959; Stockholm, Mod. Mus.; see also Meta-matic no. 1, 1959). These were portable machines with drawing arms that allowed the spectator to produce abstract works of work automatically. They were first exhibited at the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris in 1959; not all of the Meta-matics functioned properly, and Tinguely destroyed some of them. He then began to incorporate electric motors into his works, taking as his models the ‘roto-reliefs’ created by Marcel Duchamp.

In 1960 Tinguely’s friendship with Arman, César, Raymond Hains, Yves Klein and other artists, and the art critic Pierre Restany (b 1930), led to the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, which aimed at a reassessment of artistic form and material. His involvement with the group led to the Baluba sculptures, a series of primitive figures incorporating rags, fur, feathers and wire, animated by a motor (e.g. Baluba XIII, 1961; Duisburg, Lehmbruck-Mus.), and also to the Poor Ballet (1961, priv. col., see Bischofberger, p. 120), an assemblage of objects and clothes suspended from a ceiling that could be made to dance, again by means of a motor. The Transportation, on the other hand, a public procession of sculptures from Tinguely’s studio to the Galerie des Quatre Saisons on 13 May 1960 that included the scrap-assemblage Gismo (1960; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.), showed the influence of the Fluxus group, while his self-destructing works should be seen in the spirit of neo-Dadaism. These included the Homage to New York (1960), which burst into flames outside MOMA, New York, the Study for an End of the World 1, which was set to self-destruct in the grounds of the Louisiana Museum, Humblebaek, when the exhibition Bewogen Beweging (Movement in Art) moved there in 1961, and an exploding sculpture of a bull for a fiesta in honour of Salvador Dalí in Figueres.

In the mid-1960s Tinguely produced his first monumental works for an urban setting. Welded together from scrap metal, they seem like monuments to the decline of the 19th-century cult of steam. Eureka (h. 8 m, 1963/4) can be regarded as the most important work of this period; produced for Expo 1964–Schweizerische Landesausstellung, Lausanne, in 1964, it is now next to the Zürichhorn Casino by the side of Lake Zurich. In 1964 he began living with Niki de Saint Phalle, and in 1966 he collaborated with her and Per-Olof Ultvedt on the monumental sculpture She (12 m×8 m×28 m; ex-Stockholm, Mod. Mus.; destr.). Throughout the 1960s he continued to work collaboratively with, among others, Arman, Martial Raysse, Edward Kienholz, Bernhard Luginbühl and Robert Rauschenberg. In 1970, to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the founding of Nouveau Réalisme, he built a gigantic phallus (h. 8 m), which he exploded outside Milan Cathedral.

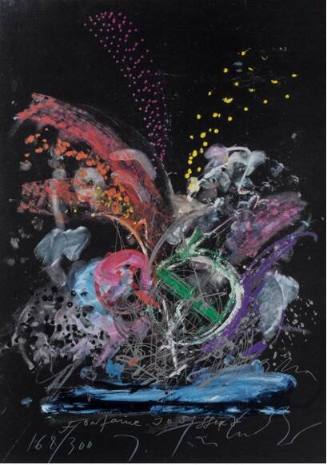

In the 1970s Tinguely began designing a number of fountains, such as that on the Theaterplatz in Basle (1975–7; see [not available online]), but in the late 1970s his work took a new direction. In gigantic reliefs, such as Fairy-tale Relief (1978; Duisburg, Lehmbruck-Mus.), links with traditional image-forms appear. In 1983 he returned to an earlier theme in one of his finest projects, the Stravinsky Fountain, next to the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. This was another collaborative effort. The voluminous, colourful vegetal forms are the work of Saint Phalle, while the black metal mechanisms were devised by Tinguely. A series of three-part altars entitled Poja (1982–4; Düsseldorf, Gal. Marika Schmela) seemed to suggest a new religious dimension to his work in the 1980s, and in Mengele, a series of 16 sculptures begun in autumn 1986, he dealt with another previously unfamiliar theme, death. Stimulated by his own physical illness, Tinguely presented a kind of danse macabre in the form of a mechanical theatre, to show the cruelty and absurdity of human life.

Tinguely owed much of his great popularity to the wit, charm, irony and sincerity of his objects. The movement of his machines was not logical or sequential, but haphazard and simultaneous. Sometimes the working of the parts and thus of the machines was quite unpredictable, resulting in a bewildering abundance of processes. With the frequently discordant sound effects that accompanied some of them, they are like caricatures of the utilitarian, mechanical world, embodying Tinguely’s critical posture towards technological optimism and his divergence from the Italian Futurists’ belief that movement imbued with technology represented the most important objective of modern art.

Gerhard Graulich. "Tinguely, Jean." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T085149 (accessed March 8, 2012).