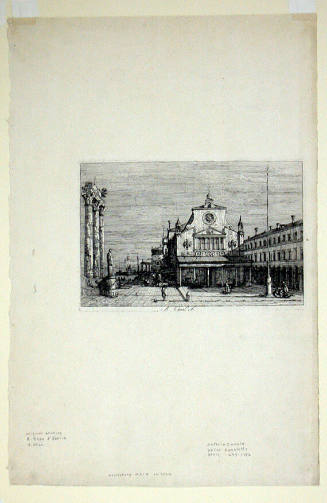

Bernardo Bellotto

Italian, 1720 - 1780

Italian painter and draughtsman. He was a view painter who worked in Italy and later at the courts of Dresden, Vienna, Munich and Warsaw. The nephew and almost certainly the pupil of Canaletto, outside Italy he signed his works de Canaletto and hence became known as Canaletto. He painted both topographical and imaginary views in a style independent of his uncle’s, distinguished by cold colour and by the austere geometry of architectural masses.

1. Early work, to 1747.

Bellotto was the son of Lorenzo Bellotto, whose origins and occupation are obscure, and of Fiorenza Domenica Canale, sister of Canaletto, the most celebrated exponent of view painting and almost certainly Bellotto’s teacher. Bellotto’s early induction into the Fraglia dei Pittori (the Venetian painters’ guild) in 1738 suggests influential backing; and in the mid-1730s Canaletto, at the height of his first fame, undoubtedly required assistance on his immense output. Bellotto’s earliest attributed works were clearly produced under his uncle’s influence. Examples include the limpid painting of the Grand Canal with S Maria della Salute (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam), and the drawing of the Piazza S Marco and the Piazzetta (Darmstadt, Hess. Landesmus.), which differs slightly in viewpoint from Canaletto’s version (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.) and shows distinct differences in handling. The Cambridge picture was ascribed to Canaletto until 1902 (Earp), and other Venetian paintings, such as the stately Grand Canal towards the Palazzo Balbi (Lyon, Mus. B.-A.), have been variously credited to Canaletto and even Michele Marieschi before being returned to Bellotto’s oeuvre. The inevitable resemblances between paintings of similar locations, coupled with the stylistic vagaries of a developing technique, make these early attributions problematical. It is nevertheless clear from them that Bellotto was already versed in the mechanical techniques employed by his uncle, especially the use of the camera obscura.

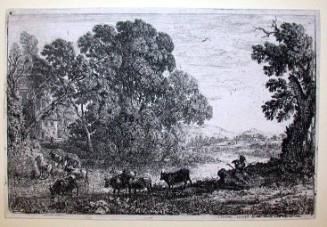

Bellotto’s first incontestable works are those he created during his Italian travels in the 1740s. At the beginning of the decade he accompanied his uncle on a trip along the Brenta canal to Padua. The result was a series of drawings (many in Darmstadt, Hess. Landesmus.), subsequently translated into a few paintings (e.g. Dolo, Looking along the Brenta; Henley, Viscount Hambleden priv. col.; see Kozakiewicz, ii, p. 29), and several etchings, which reveal his nascent interest in open spaces, clear light and boldly simple architectural forms. They also inspired his first vedute ideate (imaginary views), such as the Imaginary View of the Lock at Dolo (c. 1745; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.). In 1742 Bellotto undertook a more extensive journey on his own, possibly at the expense of Josef Wagner (1706–80), a printer who had published many engravings after Canaletto. Bellotto’s trip, to Florence, Lucca and Rome, was to bring a sharp accentuation of individuality to his work. His scenes of Florence, such as the View of the Arno towards the Ponte Santa Trìnita (Budapest, Mus. F.A.) and View of the Arno towards the Ponte alla Carraia (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam)—not companion pieces—reveal his instinctive response to familiar features such as water, sky and indeed (surprisingly Venetian) gondolas, but also to the more even atmosphere and more insistently geometric architecture. In the views of Lucca, architectural elements bulk even more largely, as in the austere Piazza S Martino (York, C.A.G.) and the expressively weighty drawing of Lucca Cathedral from the South-east (London, BM). But it was Rome that produced his first masterpiece, the Tiber with the Castel Sant’Angelo (Detroit, MI, Inst. A.), in which the melancholy repetition of the arches of the bridge is counteracted by the imposing curve of the castle and the distant lightness of St Peter’s. In marked contrast is the restlessness of the clashing verticals and diagonals of the Capitol with S Maria d’Aracoeli (Petworth House, W. Sussex, NT), with its almost abstract effect.

In the period 1743–7 Bellotto made various other excursions in Italy. The first was probably to Lombardy, where he created increasingly poetic works, such as the gloomily romantic Vaprio d’Adda (1744; New York, Met.) and the Villa Melzi d’Eril (1744; Milan, Brera), isolated in a vast plain before the distant mountains; they signal his true artistic independence from Canaletto, and indeed his search for subject-matter outside Venice may have been partly due to a desire to distinguish his work from his uncle’s. His views of Verona show him responding again to austere architectural forms, while those of Turin, such as the magnificent pair of the Palazzo Reale and the Old Bridge over the Po (both 1745; Turin, Gal. Sabauda), are full of colour and light, heightened by sharp accents and blocks of shadow. During this period he also painted imaginary views using elements from his earlier travels, like the four Architectural Capricci with Roman Motifs (Parma, G.N.).

2. Dresden, 1747–58.

Bellotto was invited to Dresden in 1747 by its ruler, Frederick-Augustus II, of the house of Wettin, Elector of Saxony and (as Augustus III) King of Poland. It has been suggested that the Elector really wanted Canaletto, who refused the invitation; in fact Canaletto had left Venice for England the year before. Bellotto had by this time married (possibly as early as 1741) and had a son, Lorenzo (b 1744). It may have been the need to support his family that encouraged him to leave the declining market in Venice for a regular salary. His remuneration was the highest ever paid to an artist at the Saxon court; the following year he became the official court painter. He responded by painting one of his most masterly works: Dresden from the Right Bank of the Elbe, below the Augustusbrücke (1748; Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister). This superb scene reflects his continued interest in the visual dynamic of the repeated arches of a bridge and also his mastery of architecture—the dominant mass of the Hofkirche (and its scaffolded tower) to the right and the dome of the Frauenkirche in the background. The whole is bathed in varied gradations of light and shadow and realized in an elegantly restricted palette of blue, brown and neutral tones.

The buildings described so magisterially by Bellotto were part of Frederick-Augustus’s plans to make Dresden one of the major capitals of Europe. The Elector transformed his city and court not only architecturally, but also by gathering there a remarkable collection of mainly foreign artists, particularly Venetians. Bellotto suggested a congenial atmosphere in one of his earliest works there, Dresden from above the Augustusbrücke (1747; Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister), where he is seen drawing the scene in happy conversation with the versatile Christian Wilhelm Ernst Dietrich and with the established court painter Alexander Thiele (1685–1752), who represents a local tradition of view painting that was rare in Germany. Bellotto discovered a remarkable variety of types of view in Dresden, from the quaint moats and walls of the old fortifications and the domesticity of the old and new market places, dominated by their old and new churches, to more rigorously architectural visions of these same churches and dramatic views of the city’s most famous building, the Zwinger, recently laid out to the designs of Matthaus Daniel Pöppelmann. The series of large paintings for the Elector (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister) and the accompanying series for the prime minister, Heinrich, Graf von Brühl (dispersed), included not only depictions of the royal residences but a surprisingly wide range of landscapes and panoramas, including the suburban village of Pirna and dramatic views of the nearby castle of Königstein. That these were part of the original commission is confirmed by instructions from the court to the Pirna authorities for Bellotto’s accommodation there. It may be that Frederick-Augustus was proud of these strategic defences of his city. If so, he was to be disappointed; within months of the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in 1756, his army had capitulated, and Dresden was occupied by the Prussians. Bellotto moved out to Pirna, to complete the last of his commissioned scenes, but these were never paid for and ended up outside Saxony, like the magnificently composed Königstein from the North (c. 1757; Knowsley Hall, Lancs), outlined darkly against a brilliant sky. Frederick-Augustus himself had already departed for his other capital of Warsaw, accompanied by his younger sons and the Graf von Brühl, leaving his wife, eldest son and grandchildren in Dresden. Similarly in 1758 Bellotto left his wife and daughters there, taking his son with him to find work in Vienna, perhaps in response to a specific invitation.

3. Vienna, Munich and Dresden, 1758–66.

Bellotto’s work in Vienna, following a more systematic pictorial programme than in Dresden, suggests such an invitation. It comprised the newest imperial residences, the most elegant modern public and private buildings and panoramas of fashionable suburbs; views of squares and streets are noticeably dominated by adjacent large buildings (for illustration of Vienna from the Belvedere see [not available online]). In all there seems to be a greater emphasis on content than on setting, on solid rather than on space. This is reinforced by larger and more individual figures and by elements of narrative. One of his finest Viennese paintings, Schönbrunn from the Forecourt (1759; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), is specifically inscribed to commemorate the Russo–Austrian victory over Prussia at Kunersdorf and shows the retinue of the messenger speeding up to the palace with the good news; it also deploys, like its companion, the sunnier and more generic Garden Front of Schloss Schönbrunn (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.; see [not available online]), a livelier chromatic scale, with accents of red and green. Two views of the Liechtenstein Palace in the Rossau (c. 1760; Vienna, Fürst. Liechtenstein Gemäldegal.) have foreground figures that are evidently portraits (studies for them survive in Warsaw, N. Mus.). City scenes such as that of the Universitätsplatz (c. 1760; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.) show a new appreciation of both the bulk and the surface of architectural forms. Bellotto’s views of the imperial retreat at Schlosshof are more traditionally topographical, though with a refreshing lightness; quite different is that of the Ruined Castle of Theben, which, with its stormy sky and foreground gypsy encampment, seems an attempt to capture some of the poetic drama of Salvator Rosa (all c. 1760; Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.).

At the beginning of 1761 Bellotto, armed with a letter of recommendation from Maria-Theresa to the Electress of Bavaria—Augustus of Saxony’s daughter Maria Antonia—arrived in Munich. There he painted some panoramic views of the city and of the palace of Nymphenburg (all 1761; Munich, Residenzmus.), which, while recalling the more conventional compositions of his Italian period, also achieve, through their evocation of vast middle distances, a sense of mystery. By the end of the same year he had returned to Dresden. His house had been destroyed by the Prussian bombardment of the previous year but his family was safe. He depicted the melancholy subject, the Ruin of Pirna, in a painting (1763–6; Troyes, Mus. B.A.) and a fine etching (probably c. 1762, but published 1766; see Kozakiewicz, ii, pp. 241–2). He also painted the shattered tower which was all that remained of the Kreuzkirche, gauntly rising out of a pile of rubble (1765; Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister). The depressing effect of such scenes may have been one reason that Bellotto turned again to the production of vedute ideate, mainly of architectural motifs inspired by memories of Venice and Rome, such as the pair featuring arcades and monumental stairways in the Staatliches Museum, Schwerin, and the trio of shaped panels (presumably intended for overdoor paintings) in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. All show a preponderance of large-scale forms and figures over surrounding space, and the overdoor panels indicate a new interest in Classical architecture. The whole series suggests an attempt to interest a new type of customer. Certainly Bellotto had a need to do so. When he returned to Dresden, the Elector and the Graf von Brühl, with most of the court, were still in Warsaw; moreover their return after the declaration of peace in 1763 did not usher in a new era of artistic patronage in Dresden. Within six months both ruler and minister were dead, and the following year the new elector also died, leaving a small son to succeed. The regent, Prince Xavier, quite properly practised post-war economies, and these particularly affected the prospects of expensive foreign artists. However, he seems to have favoured Bellotto (to one of whose daughters he was godfather), and when, with his encouragement, local painters founded an academy of arts (1764) he insisted that they should make the Venetian a member. Bellotto’s presentation piece, Dresden, the Old City from across the Elbe (1765; Karlsruhe, Staatl. Ksthalle), is understandably less serene than similar views of the 1740s but deploys the familiar elements with all his old compositional skill. In his contemporary imaginary views the new Classical bent may have been an attempt to suit his work to the indigenous artistic milieu, which was influenced by Neo-classical ideas engendered in the previous decade by the presence and the publications of Johann Joachim Winckelmann. But the salary he received as a teacher at the academy was a fraction of the lavish stipend he had been paid by Frederick-Augustus II, and he began to look for opportunities elsewhere. In 1766 he got permission to make a supposedly short trip to Russia, where the new Empress, Catherine II, was rapidly becoming known as an enthusiastic patron of foreign, and especially Italian, artists. Bellotto took with him a different kind of presentation picture, in which a particularly magnificent arrangement of columned arches and colonnaded galleries acts as setting and backdrop for a foreground portrait of the artist dressed in the robes of a Venetian nobleman (to which he had no right)—a telling illustration both of the actual power of his art and of the pretended importance of his person (1765; Warsaw, N. Mus.).

4. Late work, after 1766.

Bellotto never reached Russia. He and his son stopped off at the beginning of 1767 in Warsaw, probably to obtain letters of introduction to Empress Catherine from Frederick-Augustus’s successor in the elective monarchy of Poland, Stanislav II Poniatowski. Instead, the Polish king persuaded him to stay, as part of the royal plan to emulate the ambitious patronage of his predecessor. Bellotto, probably glad to be back in the sort of court environment he understood and certainly pleased by the King’s generous terms, agreed. In 1768 he was made court painter and summoned the rest of his family from Dresden. Stanislav’s genuine interest in the arts is attested by Bellotto’s Panoramic View of Warsaw and the Vistula from Praga (1770; Warsaw, Royal Castle), in which the King is shown, in the foreground, seated beside the artist and discussing the view and the painting. The whole dramatic and lively scene, with its stormy clouds and louring tree, contrasting groups of figures and varied boating activities, all described in a flickering evening light and with rich dark colours, is markedly different from any of the artist’s Dresden work. It does recall the rather forced romanticism of his Viennese view of Theben Castle and its gypsies; but here the drama seems genuine, a result of Bellotto’s direct reaction to the climate, atmosphere and construction of a new city.

Bellotto’s first commission in Poland was to contribute to the decoration (1767–70; largely destr.) of the King’s palace of Ujazdów outside Warsaw. He was mainly occupied with a sala terrena, which became known as the Sale de Canaletto. It was decorated with stuccos and possibly a frescoed vault and with large vedute ideate on Roman themes and perhaps some views of Warsaw. It is probable that he also painted for the Ujazdów Palace a series of observed views of Rome, based not on his own paintings and drawings of the city but on Piranesi’s famous Vedute di Roma etchings. This procedure may have arisen both from the King’s desire to have a record of all the most important ancient sites, historic squares and chief church interiors, and from Bellotto’s difficulties in producing 14 large compositions within a year. The results, as can be seen in the Forum from the Capitol and the Piazza del Pantheon (both 1769; Moscow, Pushkin Mus. F.A.), are colourful and full of incident, if hardly elegant.

Subsequently King Stanislav lost interest in Ujazdów and concentrated on the embellishment of the Royal Castle in Warsaw. After 1770 Bellotto’s work was all for the latter residence; at the same time his output slowed, for in that year his chief assistant, his son Lorenzo, died. Bernardo’s subjects were chiefly views of Warsaw and its environs. The panoramic view of Warsaw of 1770 (described above) was one of the first of these; Bellotto repeated it, with some variations, in a very fine etching of 1772 (see Kozakiewicz, ii, p. 322). Equally impressive are the paintings of Warsaw from the Terrace of the Royal Castle (1773), with its limpid evocation of distance and sky, and the Krakowskie Przedmiescie, Warsaw (1767–8; both Warsaw, N. Mus.), with its skilful deployment of blocks of buildings, spacious streets and vertical accents. The latter’s foreground, however, is busy with the figures and carriages that were to become all too prominent in Bellotto’s late work. Unfortunately, as his figures grew larger, he seems to have lost all sense of proportion, form and line when painting them. His views of Warsaw’s palaces and churches show that he did not lose these sensitivities when depicting architecture, nor his marvellous feeling for the varying tones of differing skies. An instructive contrast may be drawn between the evocative stillness of the Bernardine Church with the Sigismund Column (c. 1769; Warsaw, N. Mus.) and the same scene used as the background to the milling crowds and restless lines of scaffolding in King Stanislav Inspecting the Damage to the Royal Castle (1771; Warsaw, Royal Castle). A general falling-off might be deduced from Bellotto’s four disappointing views of the graceful country palace of Wilanow (1776–7; Warsaw, N. Mus.). But his last works, uncongenial in subject-matter and idiosyncratic in execution, evidence his strengths as well as his weaknesses. The Election of King Stanislav II Poniatowski (1776; Poznan', N. Mus.) reveals him as still incapable of organizing a composition with groups of figures yet responsive to the poetry of a vast sky above an open plain. And, in the Entry of the Polish Ambassador to Rome (1779; Wroc?aw, N. Mus.), above the formless seething mass of figures rise into the heavens the pure lines of two domes, a monument, some ruins and a soaring obelisk.

Nigel Gauk-Roger. "Bellotto, Bernardo." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T007713 (accessed March 22, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual