Karel van Mander

Born Meulebeke, nr Courtrai, West Flanders, 1548; died Amsterdam, 11 Sept 1606.

Poet, writer, painter and draughtsman.

1. Life.

Before 1568 van Mander was apprenticed to Lucas de Heere, a painter and poet in Ghent, and afterwards to Pieter Vlerick (1539–81) in Courtrai and Doornik. Between c. 1570 and 1573 he lived in his native Meulebeke, where he applied himself to writing plays and poetry. In 1573 he went to Italy, where he first paid a brief visit to Florence; in Terni he was commissioned to paint a fresco for a count of the St Bartholomew’s Night Massacre, in which the death of Gaspard de Coligny in 1572 was represented. Three sections of the fresco, restored and partly overpainted, are still extant in the Palazzo Spada Terni. In Rome he met Bartholomeus Spranger and became a close friend of Gaspard Heuvick (1550–after 1590) from Oudenaarde, who was working in Bari and elsewhere. In 1577, or shortly afterwards, van Mander was working in Basle; he then moved on to Krems. Spranger encouraged him to go to Vienna, where he worked with Hans Mont on the triumphal arch on the Bauermarkt, erected for the occasion of Rudolph II’s arrival in July 1577. After this, van Mander returned to Meulebeke, passing through Nuremberg on the journey. Because of the religious turmoil and uprising against the Spanish, van Mander and his family, who were Mennonites, kept wandering from place to place; he stayed in Courtrai and Bruges and finally fled from the southern Netherlands to Haarlem, where he arrived penniless but remained for 20 years.

In 1584 van Mander became a member of Haarlem’s Guild of St Luke. He is said to have set up a sort of academy in Haarlem at this time with Hendrick Goltzius and Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, but hardly anything is known about this project. In 1586 he worked on a gateway for the entry of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, into the city; after a difficult beginning, he established his reputation with this project. In 1603 he retreated to Zevenbergen, a house between Haarlem and Alkmaar, where he wrote the greater part of his Schilder-boeck. In June 1604 he moved to Amsterdam, where he died a poor man with outstanding debts. Jacques de Gheyn II made a drawing of him on his deathbed (Frankfurt am Main, Städel. Kstinst. & Städt. Gal.). No fewer than 300 mourners accompanied his coffin to the Oude Kerk, where he is buried.

2. Writings.

(i) Poet and man of letters.

Van Mander initially followed the style of the rederijkers (rhetoricians) but soon changed his manner under the influence of Renaissance literature. In Haarlem he was an important member of the Flemish chamber of rhetoricians called De Witte Angieren (The White Carnations), founded in 1592, for which he designed a blazon. Van Mander had a good command of Latin and Greek as well as French and Italian. Among the works he translated were Virgil’s Bucolics and Georgics (1597), Ovid (1604) and the Iliad (1611); his own writings include De harpe (‘The harp’; 1599), the Kerck der deught (‘Church of virtue’; c. 1600) and the Olijfbergh (‘Mount of Olives’; 1609). He also devised numerous inscriptions for prints, to which he always added his own motto, Eén is nodigh (‘One thing is necessary’). Van Mander was a broad-minded spirit for his time; he took a stand against Calvinism as well as Roman Catholicism. With Jan Baptiste van der Noot (c. 1540–c. 1595) and Jan van Hout (1542–1609), he is one of the best poets of the early Dutch Renaissance, whose work influenced Bredero (1585–1618) and others.

(ii) The ‘Schilder-boeck’.

The first edition was published in Haarlem in 1604; the second edition, which includes an anonymous biography of van Mander, appeared in 1618 . The Schilder-boeck, regarded as an art-historical source of great importance, consists of six sections.

(a) ‘Het leerdicht’ (‘The didactic poem’).

This is a treatise (in verse) on the theory of painting rather than a technical guide based on practice. Also known as the Grondt der edel vry schilderconst (‘Foundations of the noble free art of painting’), it comprises 14 chapters: an introduction in which the poet addressed himself to young artists, followed by chapters on drawing, the rules of proportion, pose, composition, invention, disposition (temperament), the handling of light, landscape, animals, drapery, the combination of colours, painting, colour and the meanings of colour. Van Mander based his Leerdicht on the medieval tradition of didactic poetry and on the French poésie scientifique. He used a great many literary sources, Classical as well as later, the most important of which were Alberti, Vasari and Walter Rivius. Van Mander’s approach can be described as scientific, historical, philosophical and astrological. In order to illustrate the various aspects of painting, he often referred to famous works of art or celebrated artists, who excelled in one way or another. For example, he used the Farnese Flora (Naples, Capodimonte) to illustrate drapery, Titian as the champion of brilliant flesh tone and Pieter Bruegel the elder as the master of landscape painting. In between, the poet offered various allegorical interpretations and explanations for the meaning of numerous symbols. He was the first art theorist to devote a whole chapter exclusively to landscape. In essence, the Leerdicht was an attempt to establish the superiority of the ‘free and noble art of painting’ over the crafts and trades; a similar argument ran through contemporary Italian art theory. Van Mander complained bitterly about the fact that as a painter he was forced to be a member of the same guild as tinkers, tinsmiths and rag-and-bone men, something he regarded as humiliating.

(b) ‘Het leven van de antieke schilders’ (‘The lives of the ancient painters’).

This section of the Schilder-boeck, dated 1603, is largely based on part XXXV of Pliny the elder’s Natural History. Pliny’s encyclopedia existed in a number of edited versions with explanatory notes, a number of which were known to van Mander, though he seems to have drawn primarily on the French translation by Antoine du Pinet (1562). After the introduction, in which van Mander commented on the origins of painting and sculpture—citing Homer and the reckoning of years by Olympiads—he gave biographical descriptions of Greek and Roman painters, beginning with Gyges, the first painter in Egypt. He also provided accounts of the earliest examples of Etruscan sculpture in Chiusi, Viterbo and Arezzo. The longest description is devoted to Apelles. Apart from discussing the work of ancient artists, van Mander included numerous anecdotes about the deceptive nature of realistic or naturalistic painting: Zeuxis deceived birds with real-looking painted grapes, while Parhasius deceived Zeuxis with a trompe l’oeil painted cloth apparently covering a painting. In the 16th century and early 17th Pliny’s book was mainly influential as an iconographical source; one good example is his description of Apelles’ Hercules aversus, the hero seen from behind, which gave rise to a number of such images, including Hendrick Goltzius’s famous engraving of the Farnese Hercules seen from behind (b. 143).

(c) ‘Leven van moderne beroemde Italiaanse schilders’ (‘Lives of famous contemporary Italian painters’).

This section is a translated and adapted version of Vasari’s Vite. Van Mander made a critical selection from the original text, cut down the longer passages and left out most of the portrait painters, whom he thought less important; he also discarded all decorative artists. His translation is reliable and demonstrates his good command of Italian. In the final chapters van Mander added a number of artists who had not been included by Vasari (who died in 1574). These final chapters form van Mander’s most original contribution to the discussion of contemporary Italian artists; they introduce Jacopo Bassano, Federigo Zuccaro, Federigo Barocci, Palma Giovane and Cavaliere d’Arpino. The section is rounded off with two general chapters, one about Italian artists ‘now working in Rome’, the other about Italian painters ‘working in Rome in my time, between 1573 and 1577’. Van Mander collected the material for these two chapters himself; he assembled information from Dutch artists active in Italy after 1577, such as Goltzius and Jacob Matham. Van Mander is notable for being the first literary source for Caravaggio, whose innovative naturalism he strongly opposed; he made no attempt to conceal this bias, for he believed that artists should be selective and copy only what seemed most beautiful in nature. This idealism in the representation of reality was a legacy of the Italian Renaissance, the prime exponent of which was Raphael.

(d) ‘Levens van de beroemde Nederlandse en Hoogduitse schilders’ (‘The lives of famous Netherlandish and High German painters’).

This is the most original and important part of the Schilder-boeck. It laid the foundations of the history of Dutch and German painting before 1604. Among the author’s sources were the writings of Domenicus Lampsonius, Lucas de Heere, Marcus van Vaernewijck and Pieter Coecke van Aelst, as well as letters, manuscripts, anecdotes he had heard and his own experience and memories. The first biography deals with Hubert and Jan van Eyck. Jan is compared to Masaccio and deemed the pioneer and innovator of early Netherlandish painting due to his legendary invention of oil paint. The next two chapters are about the south Netherlandish artists Hugo van der Goes and Rogier van der Weyden. In the discussion of 15th-century artists, the emphasis is placed primarily on Haarlem as the cradle of north Netherlandish painting, with Albert van Ouwater, ‘Dirck van Haarlem’ (i.e. Dieric Bouts) and Geertgen tot Sint Jans as the key figures. Haarlem seems to have been to van Mander, who, after all, worked there for 20 years, what Florence was to Vasari. The discussion of 16th-century painters is longer and more informative. There are important chapters on Dürer, Holbein and Pieter Bruegel the elder. The work of the ‘prodigy’ Lucas van Leyden he thought to equal Dürer’s achievements. Van Mander was concerned with the glory of Dutch art, for, as he proudly declared, he did not travel abroad to learn about art, ‘although Vasari wrote otherwise’. There are further important chapters largely devoted to the lives and works of contemporary artists such as Goltzius and Cornelis van Haarlem. The elaborate description of Spranger, who became a friend of van Mander’s in Rome and Vienna, is also full of vital information. This section, moreover, provides numerous facts about collectors and about paintings destroyed by iconoclasts or subsequently lost. The section ends with a discussion of some younger Dutch painters active shortly after 1600, such as Paulus Moreelse, who by 1604 had already achieved fame as a portrait painter. The index includes the names of almost 200 Netherlandish painters active before 1604, arranged alphabetically by their Christian names.

(e) ‘Uitleg en verklaring van de symboliek van de Metamorphosen van Ovidius’ (‘Interpretation and explanation of the symbolism in Ovid’s “Metamorphoses”’).

The importance of this part lies in its useful iconological information. In the artist’s biography incorporated in the second edition of the Schilder-boeck, van Mander is reported to have taught his colleagues in Haarlem ‘the Italian method, something which can be seen from the Metamorphoses designed by Goltzius’. Goltzius worked on these illustrations in close collaboration with van Mander; they began in 1587–8 but never got beyond the fourth book. There are 52 anonymous engravings, but only 6 of the original drawings have survived (Reznicek, nos 99–104; and the drawing of Apollo and Daphne, Amiens, Mus. B.-A.). The explanations in this section of the Schilder-boeck make it possible to interpret the symbolic and moral significance of a number of van Mander’s own drawings, for example that of Ixion (Paris, Louvre), which deals with punishment, ingratitude and false wisdom.

(f) ‘Hoe de figuren worden uitgebeeld, hun betekenis en wat zij voorstellen’ (‘How to render figures, what they mean and what they represent’).

In this part of the book van Mander provided his readers with iconographical–iconological guidelines in the manner of Cesare Ripa and others. Mythological gods and animals are dealt with first, then the various parts of the body, then trees and plants. Finally, van Mander discussed the abstract notions underlying these images. For instance, c. 1600 a tortoise alluded not only to slowness but also to the idea that women should stay indoors; a pair of bent knees indicated subjection; and a reed meant lack of resolution.

3. Artistic work.

Van Mander’s own work as an artist reflects his theoretical writings, and although there are only a few paintings by him, a considerable number of his drawings have been preserved, as well as at least 150 engravings after his designs. These show that he was interested primarily in ‘instructive history’—that is religious , mythological and moral–allegorical subjects—and in peasant scenes. That he believed that artists should not blindly follow nature explains why he himself never aimed at achieving realistic effects in his work. Most important to him was the poetic approach of ‘historia’; his dictum was Horace’s ‘Ut pictura poesis’. His drawings and paintings thus include neither portraits (with the exception of a signed Portrait of a Man, Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.) nor domestic scenes of the kind drawn by Goltzius and Jacques de Gheyn II, nor, for that matter, pure landscapes, animal or still-life pictures. He regarded portrait painting as an inferior, profit-seeking affair, citing Michiel van Mierevelt as an example. Landscapes could be amusing, ‘droll’ in his view, for instance the farm landscapes near Utrecht by Abraham Bloemaert. As an artist, and as a theorist, van Mander was one of the last serious followers of the Italian Renaissance in the Netherlands. When, c. 1600, a new generation of artists began to move in the direction of ‘realism’, van Mander no longer took part in artistic developments.

(i) Drawings.

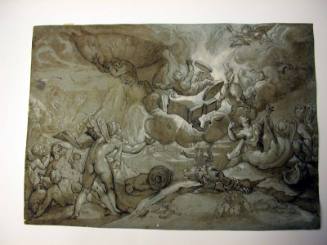

There are c. 70 surviving drawings by van Mander, 46 of which were catalogued by Elisabeth Valentiner in 1930. Only one drawing can be attributed to him with certainty from the period before 1583, the year he came to Haarlem: the Flight into Egypt (Dresden, Kupferstichkab.), which corresponds to an engraving of the same subject by Cherubino Alberti (b. 15). The early style points to the influence of Jan Speeckaert and Spranger. Later, van Mander seems to have been especially influenced by Cavaliere d’Arpino, as can be seen in the red chalk drawing of Neptune (Berlin, Kupferstichkab.; not accepted by Valentiner). After Goltzius’s return from Italy in 1591, van Mander gradually reduced the amount of exaggerated movement in his figures, and his compositions generally became more balanced, with a greater sense of depth. Among his finest drawings are those of Apollo and Daphne and Pan and Syrinx (both Florence, Uffizi), which are in the manner of Spranger, and that of Diana and Actaeon (Bremen, Ksthalle), which shows a splendid use of colour and seems related in concept to van Mander’s lost tapestry designs. Besides religious and mythological subjects, he also represented peasant scenes in imitation of Pieter Bruegel. His brilliant watercolour sketches in the Italian manner were based on woodcuts after Parmigianino.

Most of van Mander’s designs for engravings, which were executed by Jacques de Gheyn II, Jacob Matham, Zacharias Dolendo and others, have been lost, but the prints show him to have been an imaginative inventor. The captions underneath the prints often help elucidate the symbolical meaning of the image, which usually has some underlying Christian moral; they were written either by van Mander himself or by Latin schoolmasters in Haarlem, such as Franco Estius (b c. 1544) and Theodore Schrevelius.

Van Mander’s drawings include no academic studies of nudes, which is curious, given his alleged involvement with an academy in Haarlem where artists could draw models and make use of other facilities. His drawing of a Male Nude (Amsterdam, estate of J. Q. van Regteren Altena, see Valentiner, no. XI), seen from behind in an elegant pose, seems to have sprung from the artist’s imagination rather than anything he might have seen in reality. And although there are a number of academic drawings of Classical statues by Goltzius, no such works by van Mander survive. Possibly they were lost en bloc.

(ii) Paintings.

There are approximately 30 surviving paintings by van Mander, on copper, panel and canvas; they were catalogued by Leesberg in 1994. The earliest painting—the altarpiece of St Catherine—was made for the clothmakers’ guild in the St Maartenskerk in Courtrai (1582; in situ). It was painted shortly before the artist moved from Flanders to Haarlem. Stylistically, it is close to the work of the so-called Flemish Romanists, such as Michiel Coxie, who were influenced by 16th-century Italian art (see Romanism). The overall impression is rather stiff and old-fashioned, as if the artist had learnt practically nothing in Italy. Van Mander seems to have deliberately adapted his style to what was then the fashionable taste in Flanders.

Most of van Mander’s paintings, however, were carried out in the northern Netherlands after 1583. Yet his colours continue to betray his Flemish background; they are similar to those of the Bruegel family: usually brown in the foreground, green in the centre and pale blue in the background. The figures are clothed in gentle tones, with sufficient contrasts of yellow, red and blue. The compositions are schematic and follow the rules set out in the Schilder-boeck: clusters of trees on the edges, a distant view in the middle (often showing a river winding through a landscape) and the narrative taking place in the foreground. Typical examples are the Continence of Scipio (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and Mankind before the Flood (Frankfurt am Main, Städel. Kstinst. & Städt. Gal.). On the verso of the former, van Mander painted an appropriate allegorical scene, something he did in a few other cases as well. His landscapes reveal the influence of Gillis van Coninxloo, with whom he collaborated on several occasions; van Mander, for example, painted the figures in van Coninxloo’s Judgement of Midas (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister).

E. K. J. Reznicek and M. J. T. M. Stompé. "Mander, van." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053701pg1 (accessed May 8, 2012).