Gianlorenzo Bernini

Italian, 1598 - 1680

Sculptor, architect, draughtsman and painter, son of Pietro Bernini. He is considered the most outstanding sculptor of the 17th century and a formative influence on the development of the Italian Baroque style. His astonishing abilities as a marble carver were combined with an inventive genius of the highest order. From the mid-1620s the support of successive popes made his the controlling influence on most aspects of artistic production in Rome. Although his independent works of sculpture, both statues and portrait busts, are among the most brilliant manifestations of their kind in Western art, his genius found its highest expression in projects in which he combined sculpture, painting and architecture with scenographic daring and deep religious conviction to express more fervently than any other artist the spiritual vision of the Catholic Counter-Reformation Church.

Bernini was not often active in the decorative arts, but was nonetheless influential on furniture design. The wooden plinth shaped like a burning log that he designed for his marble statue of St Lawrence on the Grill (c. 1618; Florence, Pitti) proved to be a seminal influence on the design of plinths and tables. He is also known to have designed silver (a reliquary and candlesticks), but none survives, nor does the coach that he designed for Queen Christina of Sweden (reg 1632-54).

Notwithstanding the overlapping aspects of Bernini's projects, his works are here categorized according to the dominant element in each (e.g. the St Peter's baldacchino is considered within the discussion of his sculpture, as is the Cornaro Chapel, which focuses on the Ecstasy of St Teresa; his work at S Andrea al Quirinale is discussed under architecture .

I. Life and work.

1. Sculpture.

(i) Training and early works, to 1623.

Gianlorenzo trained as a sculptor in his father's studio and maintained links with it until Pietro's death in 1629. Reports of him as a child prodigy who was practising as a sculptor at the age of eight are given in biographies written by his son Domenico Bernini and by Filippo Baldinucci. It must be assumed that he collaborated as a child on the works being created in his father's studio. This explains the astonishingly early date of the first documented work that can be attributed to him, the sharply realistic marble bust of Dr Antonio Coppola (1612; Rome, S Giovanni dei Fiorentini), which was based on a death mask. Bernini was, however, producing sculpture even before this. The small marble group of the Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Faun (c. 1609; Rome, Gal. Borghese), made for Cardinal Scipione Borghese (see Borghese, (2)), follows the model of Hellenistic and Roman scenes with Bacchic children, a genre in which Pietro Bernini had excelled. In this early masterpiece Bernini, barely 10 years old, was using an approach that was in sharp contrast to the complicated artificiality of his father's sculpture, showing a new simplicity and naturalness and a mimetic virtuosity in the representation of animals and nudes.

Bernini's second important patron, Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (later Urban VIII), may have been involved with the creation (although it was not a specific commission) of St Lawrence on the Grill (Florence, Pitti), an under life-size marble figure already showing the influence of Michelangelo. Barberini's commission for a marble St Sebastian (Lugano, Col. Thyssen-Bornemisza) was linked with the decoration of his family chapel in S Andrea della Valle, Rome.

After these small and medium-sized works Bernini was commissioned by Scipione Borghese to produce a series of over life-size marble statues for his new villa by the Porta Pinciana, Rome. These technically brilliant and surprisingly novel works rapidly turned Bernini into a European celebrity. His first achievement as a monumental sculptor was Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanius Leaving Troy (1618-19; Rome, Gal. Borghese), a work once attributed to Pietro. Evoking the passage in the Aeneid in which Aeneas carries his father and leads his son away from the burning city, the group is notable for the realistic characterization of the three figures, their relative positions introducing a new naturalism. There is still greater naturalism in Pluto and Proserpina (1621-2; Rome, Gal. Borghese), an explosive combination of motion and emotion in which Pluto strides vigorously forward carrying the struggling Proserpina across the threshold of the underworld, represented by the snarling, three-headed dog Cerberus. Soft flesh yields to the violent grasp of the muscular god as marble tears course down Proserpina's cheeks. The impact of this over life-size group is intensified by its placement indoors on a low pedestal and set against a wall commanding a frontal viewpoint.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: Apollo and Daphne, marble, h. 2.43 m, 1622-4…The spectacular Apollo and Daphne (1622-4; Rome, Gal. Borghese) was inspired by a passage in Ovid's Metamorphoses and was conceived, in part, as a challenge to both poetry and painting. The metamorphosis of Daphne into a laurel tree is a technical tour de force representing an apparent transmutation of marble into leaves, bark, cloth and flesh. This hallucinatory realism is matched by an extraordinary temporal innovation. The group was originally placed in a room against an interior wall close to two corner doors. Upon entering, the viewer would see only the back of Apollo and his flowing drapery, the drama unfolding in real time and space as the spectator went further into the room. Here Bernini controlled the viewer's experience, as he did later on a much larger scale in St Peter's.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: David, marble, 1623 (Rome, Galleria Borghese); photo credit:…Bernini's David (1623; Rome, Gal. Borghese), begun after Apollo and Daphne but finished before, was the last statue he created for Cardinal Borghese. The vigorous pose is akin to the model of a man throwing a spear or stone in Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della pittura (for further discussion see Lavin, 1985, pp. 1-23), a model followed by Annibale Carracci in the figure of Polyphemus on the ceiling of the gallery of the Palazzo Farnese.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children, marble, h.…In these Borghese marbles Bernini responded to and competed with the new naturalism of contemporary painting as seen in the work of Annibale Carracci and Caravaggio. He felt that one of his greatest achievements was to have made marble appear as malleable as wax and so, in a certain sense, to have combined painting and sculpture into a new medium, one in which the sculptor handles marble as freely as a painter handles oils or fresco (see also Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children, c. 1616-17; New York, Met.).

During this early part of his career Bernini was also active as a restorer of antique sculptures. The most important of his restorations are those known as the Borghese Hermaphrodite (Paris, Louvre), to which around 1622 he added a marble mattress, the Ludovisi Mars (Rome, Mus. N. Romano) and the Barberini Faun (Munich, Glyp.) The most distinguished part of his non-monumental output was, however, his impressive series of portrait busts. From perhaps the earliest, the small portrait of Giovanni Battista Santoni (marble, 1610; Rome, S Prassede), to those of Mgr Pedro de Foix Montoya (marble, c. 1621; Rome, S Maria di Monserrato), one of his principal works as a portrait sculptor, and the half-length of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino (marble, Rome, Gesù), Bernini brought to portraiture a new sense of realism, formal subtlety and psychological intimacy. In recognition of his achievements Bernini was knighted by Gregory XV in 1621, the same year in which he was elected Principe of the Accademia di S Luca.

(ii) The St Peter's baldacchino and other works for Urban VIII, 1623-44.

On 6 August 1623 Cardinal Maffeo Barberini was elected pope as Urban VIII (see Barberini, (1)). The elevation of Bernini's close friend and patron initiated a relationship that was to have a profound impact on the artistic life of Rome. Indeed, Urban's plans for and confidence in the young Bernini were heralded by the Pope's declaration, recorded by Baldinucci, made soon after his accession: 'It is your great good luck, Cavaliere, to see Maffeo Barberini Pope; but we are even luckier in that the Cavaliere Bernini lives at the time of our pontificate'. Urban VIII gave Bernini a supreme position that he sustained with only brief interruptions for the rest of his life. Inspired by the example of previous popes (notably Julius II's patronage of Michelangelo), he engaged Bernini to work not only in sculpture but in architecture and painting.

The discovery of the remains of the early Christian martyr St Bibiana led to Bernini's first completed project for Urban VIII, the reconstruction in 1624-6 of the small church of S Bibiana (see §3(i) below) and the carving of a life-size statue. Bernini's marble, set in a niche above the high altar, shows the young saint with an open-handed gesture leaning against a column (an allusion both to her martyrdom and her fortitude) as she gazes serenely upwards at Pietro da Cortona's fresco depicting God the Father. This sublime emotion, which recalls that expressed in Bernini's Anima beata (marble; Rome, Pal. Spagna), an earlier bust, makes the statue an affirmation of pure faith, an emblem of Counter-Reformation spirituality.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: baldacchino, gilt-bronze and marble, 1623-34 (Rome, St Peter's);…After the completion of the façade of St Peter's (fabric consecrated 1626), attention turned to the decoration of the vast interior of the church. Bernini embarked on a series of projects that eventually filled the basilica with major works celebrating the primacy of the papacy and the Roman Catholic Church. (For a discussion of Bernini's work at St Peter's in the context of the contribution of other artists see Rome, §V, 14(ii)) His first effort for Urban VIII, which occupied him and a small army of assistants, including Francesco Borromini, for more than a decade, was the erection of a monumental structure beneath Michelangelo's dome in the centre of the crossing to mark the site of the first apostle's grave and papal altar. The famous baldacchino (1623-34), consisting of four colossal spiral gilt-bronze columns set on high marble bases and joined by a cornice, rises over the high altar (see fig.). Above each column stands a twice life-size angel holding in each hand garlands that disappear under the volutes of the ribbed superstructure as if supporting it. The form of the columns was inspired by a group of spiral marble columns from Old St Peter's thought to have been brought by Constantine the Great from the Temple of Jerusalem. In his design for the baldacchino, Bernini alluded to a series of earlier projects for the crossing, as well as to structures known from the early history of St Peter's, by combining the permanence of an architectural ciborium, the mobility of a portable canopy carried by acolytes and the sacred, ceremonial symbolism of the suspended baldacchino to create an architectural chimera that is also a mystical event-four bronze columns crowned by a superstructure carried there and held in place by angels. While it is generally agreed that Bernini was the originator of the overall design, the exact role of Borromini, who was assigned to Bernini's team as a draughtsman and technical adviser, is controversial (see Borromini, francesco).

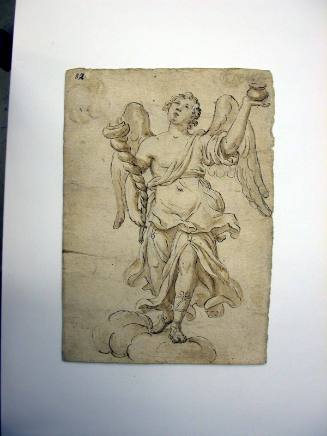

As work on the baldacchino progressed, Bernini, from 1629 architect to the fabric of St Peter's, was charged with systematizing the display of three Early Christian relics housed from 1606 in niches in the crossing piers flanking the apse: the head of the apostle Andrew; the lance of Longinus; and Veronica's veil. These relics, along with fragments of the True Cross brought to Rome by St Helena and transferred to St Peter's in 1629 by Urban VIII, were assembled by Bernini in the crossing. Each relic was honoured by the decoration of one of the giant piers. Bernini divided each pier into an upper and lower section. In the latter he created a large niche for a colossal marble statue of the saint, while the relic itself was commemorated in a tabernacle framed by a pair of spiral marble columns from the original Constantinian basilica, thus stressing the continuity of place. The statues, some three times life-size, were designed by Bernini and carved by him and by sculptors working under his control: St Andrew (1629-39) by François Du Quesnoy; St Longinus (1631-8) by Bernini; St Helena (1631-9) by Andrea Bolgi; and St Veronica (1631-40) by Francesco Mochi. In pairs and as a group they relate to the baldacchino. St Veronica and St Helena seem to direct their attention to and move towards the papal altar at which Christ's Passion is re-enacted during Mass. St Andrew and St Longinus, with arms outspread in wonder, look upward towards the top of the baldacchino, where Bernini had envisaged a huge statue of the Risen Christ (see Lavin, 1968, figs 31, 79). The ecstatic reaction of the male saints is a response to Christ's triumph over death, a concept maintained with the globe surmounted by a cross, a modification made by Bernini for structural reasons. Bernini thus charged the space of the crossing with an unprecedented dramatic power, engaging spectators physically and psychologically and making them not merely witnesses but participants in the unfolding events.

In 1629, as work continued on the crossing, Guglielmo della Porta's tomb of Paul III (1549-75), then located at the south-east pier where Du Quesnoy's St Andrew now stands, was moved to the left side of the apse. This massive tomb became the model for Bernini's funerary monument of Urban VIII (1627-47), positioned at the right side of the apse. Composed of bronze, gilt bronze, and white and coloured marbles, it is of extraordinary visual richness and conceptual subtlety. The over life-size gilt-bronze effigy of the Pope, shown seated, swathed in magnificent robes and making a lordly gesture, looks out towards the baldacchino from a high marble platform. Below him is a bronze sarcophagus on which a winged bronze skeleton enters the Pope's name in a gold inscription in his bronze book of the dead. The sarcophagus is flanked by two marble allegorical groups representing Charity and Justice. Unlike the ideal, abstract virtues on the tomb of Paul III, Bernini's personifications are made startlingly life-like through the informal poses and emotional immediacy of the figures. Charity turns towards a weeping child with a look of maternal consolation and understanding; Justice, books closed and scales dismounted, slumps against the end of the sarcophagus overcome by sadness as three Barberini bees (heraldic devices of Urban VIII), disorientated by the loss of their master, alight randomly on the tomb. The monument serves as a reminder that death and time, though victors here, are ultimately vanquished by a greater force. The tomb of Countess Matilda (marble; 1633-7), a figure whom the Pope held particularly dear as a fellow Tuscan and as the ideal secular ruler in her relations with the Holy See, was also commissioned by Urban VIII for this part of St Peter's; Luigi Bernini collaborated on this work.

Bernini's two over lifesize marble busts of Cardinal Scipione Borghese (both 1632; Rome, Gal. Borghese) represent a distinct change from his earlier portraiture. The second bust was secretly carved in either three or fourteen days (depending on the source), a flaw in the marble having caused a crack across the forehead of the first (the two are otherwise identical). innovative for their lifelike quality, these busts show the Cardinal alert and informal with lips parted as if to speak, conveying a sense of spontaneous vigour. The same passionate vitality is evident in the marble bust of Bernini's mistress Costanza Buonarelli (1635; Florence, Bargello). Her intelligence and sensuality are embodied by an intimate naturalism unequalled until the art of Jean-Antoine Houdon in the 18th century.

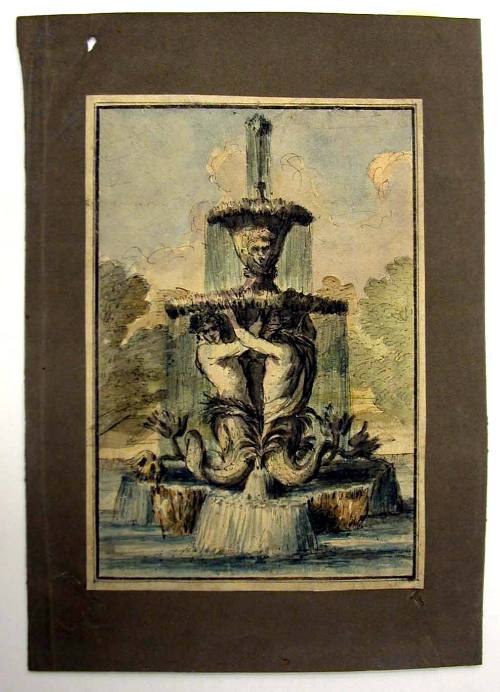

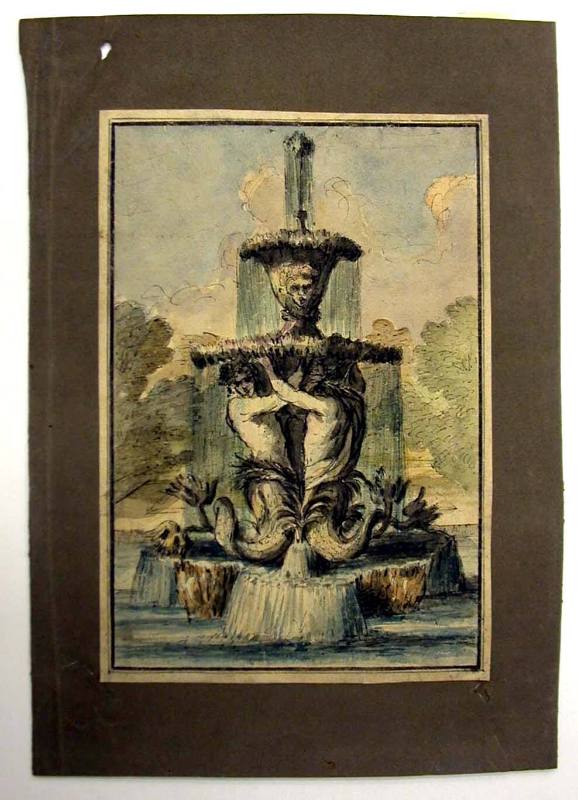

Besides a monumental seated effigy of Urban VIII (marble, 1635-40; Rome, Mus. Conserv.), Bernini also executed busts of the Pope (e.g. marble, c. 1640; Rome, Pal. Spada) and members of his family. His last major commission for this papacy was for a fountain outside the family palace at Piazza Barberini. With the Triton Fountain, completed in 1642-3, Bernini abandoned the staid, architectural format of earlier fountains to create a spectacle. Four dolphins, tails entwined around the papal coats of arms and supporting a giant bivalve, arise from a pool of water. The sea god Triton, seated in the middle of this great shell, blasts a thunderous stream of water heavenward from a massive conch shell. The base, basin and figure are integrated into an organic, poetic whole, which Bernini intended as a celebration of Urban VIII's rule.

(iii) The Cornaro Chapel and the Four Rivers Fountain, 1644-55.

The death of Urban VIII in 1644 signalled a dramatic decline in Bernini's fortunes. The odium attached to everyone tied to the late Pope extended to Bernini, who suddenly found himself out of favour with the newly elected Innocent X (see Pamphili, (1)). Stripped of papal protection, Bernini was attacked by rivals long excluded from choice church commissions through his near monopoly of artistic control. His fortunes reached their nadir in February 1646 when, after he was charged with incompetence by Borromini and others, the bell-towers he had constructed at St Peter's were demolished because of structural faults (see §3(i) below). This public disgrace led Bernini to embark on a work for himself, a monumental marble group of Time Discovering Truth Hidden in a Cave. Only the nude female figure of Truth (1647-52; Rome, Gal. Borghese) was completed, a large, ungainly, smiling girl gazing upward towards her rescuer. The representation of the 'naked truth' remained in Bernini's possession until his death, a private emblem of vindication and faith in the divine and a harbinger of the highly personal, emotive figural style he developed in the last decades of his life.

Papal neglect allowed others to engage Bernini's services, and in 1647 he began the project that stands as perhaps his greatest achievement and the paradigmatic example of 17th-century art, the Cornaro Chapel (1647-52) in S Maria della Vittoria, Rome. Indeed, of all his works it was the one that Bernini, always self-critical, considered 'the least bad' (see Domenico Bernini). He was commissioned by the Venetian Cardinal Federigo Cornaro (1579-1653) to decorate a small chapel forming the left transept of the early 17th-century church. The patron wanted to construct a mortuary chapel for himself, commemorate seven other distinguished members of his family and, especially, honour St Teresa of Avila, the 16th-century Spanish mystic and Carmelite reformer canonized in 1622.

Bernini retained the existing order of colossal pilasters and continuous entablature that defines the entire interior fabric of the church, weaving into it a similar order of pilasters and entablature to define the back and side walls of the chapel. Into this matrix he set the pedimented altar tabernacle, framed by double columns, with the marble group of the Ecstasy of St Teresa, which shows the saint recumbent on a cloud and an angel piercing her heart; the sculpture is illuminated by a hidden window. Below, the front of the altar is decorated with a gilded bronze relief of the Last Supper. In choir-boxes on each side wall four portraits of male members of the Cornaro family, seen against an architectural backdrop, read or are engaged in discussion. Two roundels in the pavement represent skeletons rising in prayer and wonder. Framed narrative relief scenes in gilt stucco based on events in the life of St Teresa decorate the chapel's vault, while at the very apex is a fresco, executed by Guido Ubaldo Abbatini, of the dove of the Holy Spirit accompanied by a host of cloud-borne angels. This fresco covers the upper sections of the narrative reliefs and overlaps portions of the central window frame. White stucco angels holding books, garlands and, at the very top, a floral crown hover along the entrance arch.

The unity of sculpture, painting and architecture makes the chapel one of Bernini's greatest achievements. Its central feature is the Ecstasy of St Teresa, which focuses on the moment of the transverberation. Teresa herself described the event in which an angel appeared to her: 'he was holding a long golden spear, and at the end of the iron tip I seemed to see a point of fire. With this he seemed to pierce my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he drew it out, I thought he was drawing them out with it and he left me completely afire with a great love for God.' (See Saint Teresa of Jesus: The Complete Works, 3 vols, ed. and trans. E. A. Peers (London and New York, 1963), i, p. 192.) Bernini depicted Teresa in an attitude of ecstatic abandon, a spiritual swoon caused by the love of God; there are also allusions to her levitation upon receiving the Eucharist at Mass, her mystic marriage to Christ and her miraculous death. This complex of ideas symbolized God's love for mankind as expressed through St Teresa as intercessor and through the eucharistic sacrifice with its promise of eternal salvation. The entire programme relates directly to the mystical event taking place at the altar. The dead rise from their graves through the chapel floor; members of the Cornaro family bear witness to the portentous significance of this proof of divine love, and the Holy Spirit and angels descend into the actual space of the chapel in celebration of this moment. St Teresa is an example to Federigo Cornaro, his family and all humanity of the promise of salvation. The visual logic of the composition is inextricably bound to the conceptual complexity of the spiritual themes. This programmatic and aesthetic unity represents the culmination of Bernini's career; a perfect union of form and content.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: Four Rivers Fountain, marble, 1648-51, Piazza Navona, Rome;…In 1647 Innocent X was tricked into viewing Bernini's model for a fountain in the centre of the Piazza Navona, which he wished to transform into the grandest public square in Rome. Unable to resist the design, he returned Bernini to papal favour. The Four Rivers Fountain (1648-51) is Bernini's largest and most spectacular fountain, a masterpiece of engineering and urban planning and a marvel of art. Its travertine base, populated with four giant marble personifications of the rivers Danube, Nile, Ganges and Plate, supports an ancient granite obelisk moved from the Circus of Maxentius. Bernini daringly pierced the base on all sides, thus opening a view through and making the massive obelisk appear to hover weightlessly above the void. The impression of immateriality accords with contemporary interpretations of the obelisk as symbolic of the sun's rays and of the triumph of Christianity. The river gods' reaction to this miraculous apparition demonstrates its supernatural force and the power of the pope and the Catholic Church over the entire world. Bernini also redesigned the Moro Fountain (marble, 1653-5) at the south of the piazza.

(iv) The Cathedra Petri and other works for Alexander VII, 1655-65.

On his accession in 1655 Alexander VII (see Chigi, (3)) put Bernini in charge of the decoration of S Maria del Popolo. The only works there from Bernini's hand, however, are the marble niche statues of the prophets Daniel (1655-7) and Habakkuk (1655-61) in the Chigi Chapel. More importantly, the new pope revived a scheme, first discussed under Urban VIII, to build a monumental reliquary in the apse of St Peter's for the apostle's throne. The Cathedra Petri (1657-66), an immense work, perfectly proportioned to the vast dimensions of the apse and visually framed from the nave by the columns of the baldacchino, provides the climax to Bernini's work in the basilica. High above the altar, the great bronze throne of Peter seems to hover in mid-air. A relief showing Christ's charge to Peter, Feed my Sheep, decorates the chair back, while above, two putti support the papal keys and tiara. Below the throne, on a great base of black Sicilian marble and red jasper, stand colossal, gilt-bronze statues of two Greek and two Latin Fathers of the Church: St Ambrose, St Athanasius, St John Chrysostom and St Augustine. The throne is enveloped behind and below by a bank of gilded stucco clouds that have descended from the zone above. There, in the centre of an oval window, painted on the glass and radiating a brilliant aureole of yellow light, is the Dove of the Holy Spirit, surrounded by gilded stucco clouds and angels amid a burst of golden rays. As in many of his projects, Bernini incorporated a light source into the work to convey the mystical nature of the event.

(v) The visit to France and works for Louis XIV, 1665.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: modello for the equestrian statue of Louis XIV,…In March 1665, as work on the Cathedra Petri moved towards completion, Bernini left for France at the invitation of Louis XIV to discuss designs for the completion of the Palais du Louvre (see §3(iii) below). The five-month visit is recorded in the diary of his guide Paul Fréart, Sieur de Chantelou (see Fréart, (2)), a valuable source of information on Bernini and his ideas about art. Although his plans for the Louvre project were rejected, Bernini did execute a marble bust of Louis XIV (1665; Versailles, Château). The pose and drapery of this imperious portrait dominated European art for more than a century as patrons, painters and sculptors sought to emulate its image of princely authority. It is the culmination of Bernini's series of secular rulers. Louis XIV also ordered from Bernini in 1665 a marble equestrian statue of himself (see fig.), to be similar to that of Constantine the Great, which Bernini had begun preparing in 1654 for the Scala Regia at the Vatican (see §3(iv) below). The King's statue, made in Bernini's Rome workshop in 1669-77, did not arrive at the Château of Versailles until 1685. The King did not like it, perhaps finding it too Italianate for a French taste that had become classicizing in its sympathies. In 1688 it was transformed by François Girardon into Marcus Curtius Throwing himself into the Flames and relegated to a remote corner of the gardens (in situ; a lead cast now in front of I. M. Pei's glass pyramid, Louvre, Paris).

(vi) The tomb of Alexander VII and works for Clement IX, 1666-80.

Bernini completed a number of equally notable sculptural projects during his final years. Immediately on his return to Rome in 1666 Alexander VII commissioned him to design a setting in front of S Maria sopra Minerva for a small obelisk found near by. Bernini revived a project dating back to the 1630s, and the resultant Elephant Bearing an Obelisk was unveiled in the piazza in 1667. On his election in 1667 Clement IX (see Rospigliosi, (1)) decided to decorate the Ponte S Angelo, then the only bridge over the Tiber to the Vatican, with ten statues of angels holding the instruments of the Passion. Bernini was put in charge of the project. His own contributions were the versions of the Angel with the Crown of Thorns and the Angel with the Superscription (both marble, 1668-9), now in S Andrea delle Frate, Rome. The Pope considered these to be too fine for exposure to the weather, and modified second versions were subsequently carved and installed. In 1670 the statue of Constantine the Great (statue actually begun 1662, reviving Innocent X's project of 1654) was completed; in 1673-4 Bernini designed and executed the tabernacle and adoring angels in bronze for the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in St Peter's; and in 1674 he completed the marble altarpiece, the Death of the Blessed Ludovica Albertoni, for the Altieri Chapel in S Francesco a Ripa, Rome, which takes up some of the theatrical devices employed in the Cornaro Chapel. All these sacred works are imbued with an intense spirituality: swirling, agitated drapery courses over the figures, mirroring their exalted inner states.

The last of Bernini's great projects to be completed was the tomb of Alexander VII (1671-8). It was commissioned by the Pope before his death and was originally intended for S Maria Maggiore, but the site had been changed to the south transept of St Peter's by 1670. In 1672 Bernini was paid for the design and a model of the whole tomb. Executed almost entirely by assistants and collaborators, though under Bernini's close supervision, it consists of a marble effigy of the Pope kneeling at prayer, while below him are marble female figures representing Charity, Prudence, Justice and Truth. A bronze skeleton shaking an hourglass pushes up from under the great inlaid marble shroud that hangs over an entrance door that could not be moved and was thus cleverly incorporated into the design. Bernini's last sculpture was a half-length, over life-size marble bust of Christ (Norfolk, VA, Chrysler Mus.). Carved for himself in preparation for his death, the bust and the elaborate planned base with two kneeling angels holding Christ aloft (unexecuted) is a highly personal expression of Bernini's deep faith.

2. Painting and drawing.

Baldinucci recorded that Bernini painted more than 150 pictures 'for his pleasure and as a pastime', yet only a handful of works can be confidently attributed to him now. These include two self-portraits in the Galleria Borghese, Rome, some other portraits and two religious paintings, a David (ex-Incisa della Rocchetta priv. col., Rome; see Mahon and Sutton, no. 7) and SS Andrew and Thomas (London, N.G.). These are generally dated some time between the mid-1620s and the mid-1630s, and they belong to the Caravaggist current common to much Roman painting of the period.

Although Bernini became involved in Urban VIII's abortive plans to provide frescoes for the Benediction Loggia above the portico of St Peter's, he is not known to have executed any of the decorative paintings that play an important part in such later undertakings as the Raimondi and Cornaro chapels. He did, however, employ a number of assistants who worked under his instruction and from his designs. The painters most closely associated with him were carlo Pellegrini, possibly a pupil of Andrea Sacchi, and guido ubaldo Abbatini, who was trained in the studio of Cesare d'Arpino. Other, somewhat more distinguished artists, including Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, were also involved in projects on which Bernini worked, though they were, perhaps, allowed more freedom.

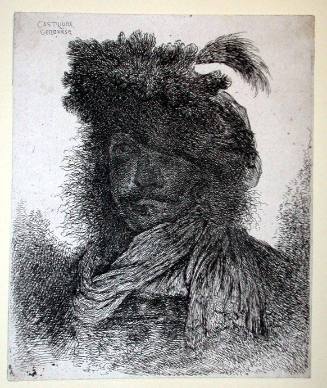

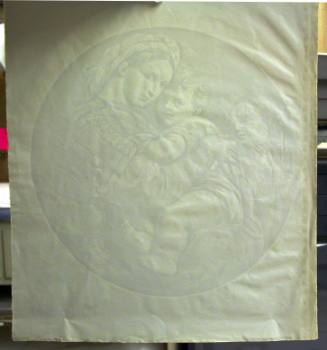

Bernini made various kinds of preparatory drawing, from summary but dynamic compositional sketches to more careful studies of particular details (see §II below), but he also produced independent drawings. Closely related in style to his known portrait paintings are portrait drawings, among them the superb Self-portrait (black chalk heightened with white on grey paper; Windsor Castle, Royal Lib.), executed in old age. There also survive some religious compositions, including a Holy Family (pen and brown ink with dark brown wash, c. 1665-70; Rome, Col. Rospigliosi-Pallavicini), which Bernini presented to Clement IX. His pioneering caricatures (e.g. Cassiano dal Pozzo, pen and brown ink on cream paper, before 1644; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans-van Beuningen) delighted his contemporaries and broke new ground in the art of social satire.

3. Architecture.

(i) Early works, additions and restorations.

Bernini's career as an architect began modestly in 1624 with the construction of the façade of S Bibiana, Rome. Small though this project was in scope, it already showed the combination of tradition and originality that was to make his architecture so influential not only in Rome but also on the course of Baroque design throughout Europe. The façade consists of an open, arcaded loggia with a palace-like storey above. The central element of this upper part is a deep, pedimented aedicule that breaks dramatically the skyline of the balustraded flanking wings.

Throughout the later 1620s and the 1630s Bernini was involved with the restoration of and additions to various buildings, including, notably, the architecture of the high altar at S Paolo Maggiore, Bologna (1634), and the apse and high altar of S Maria in Via Lata, Rome (1636-43). He collaborated with alessandro Algardi, later among his principal rivals, on the architectural catafalque for the funeral of Carlo Barberini (1630) and was also responsible for other temporary works of this kind. In 1629, on the death of Carlo Maderno, Bernini was appointed architect to the fabric of St Peter's, a position that eventually led to his greatest artistic humiliation as well as his greatest architectural success: in 1636 he designed a remodelling and completion of the two bell-towers begun by Maderno flanking the façade of the basilica. The south tower, begun in 1638, was complete by 1641; the north tower was begun in 1641 but never finished. In 1645-6, while Bernini was supervising the marble revetment and stucco decoration of the nave of St Peter's, investigations were made into cracks that had appeared in the substructure of the south tower. Amid charges of incompetence against him, the bell-towers were demolished in 1646.

(ii) Churches.

Although Bernini was involved from 1655 in the extensive works at S Maria del Popolo, Rome, it was not until 1658 that he had the opportunity to design entire churches, albeit relatively small ones. In that year he began S Tommaso da Villanova (completed 1661) at Castel Gandolfo and S Andrea al Quirinale in Rome. In 1662-4 he built S Maria dell' Assunzione at Ariccia. All three are variations on a domed, centralized plan. That at Castel Gandolfo, the papal summer residence, is the simplest, its dome set on a drum above a Greek Cross plan. The interior of the dome is decorated with the combination of ribs and coffers that Bernini used on his two other churches and that was to prove very influential. The church at Ariccia is a more interesting scheme based on a circular plan and having a hemispherical dome rising straight from the cornice of the main walls. It is entered through a triple-arched and pedimented portico with pilasters. This remarkably pure combination of cylinder, hemisphere and portico was clearly inspired by Bernini's contemporary involvement with schemes to restore the Pantheon to its 'original' state.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: interior of S Andrea al Quirinale, Rome, 1658-70;…Both S Tommaso and S Maria were built for Alexander VII. S Andrea al Quirinale, the most sophisticated of Bernini's three churches, was a project for the Jesuits funded by Prince Camillo Pamphili. It is oval in plan, with the entrance and the altar facing one another on the short axis. Bernini had already explored this arrangement in minor projects of the 1630s, including the Capella dei Rei Magi (1634; later replaced by Borromini) in the Collegio di Propaganda Fide, Rome. The interplay between the interior and the façade is complex and subtle. The tall, austere, pedimented façade, with its projecting semicircular portico and semicircular steps, establishes a contrapuntal rhythm to the concave flanking walls that intersect with it and with the oval body of the church (for illustration see Cartouche). This interplay of concave and convex elements adumbrates the spatial dynamics of the interior. There, the altar aedicule (see fig.), immediately visible on entering the church, repeats the architectural detailing of the façade while reversing its spatial thrust. Framed by massive pairs of dusty-pink marble columns, with an eccentric inward-curving pediment, the aedicule is the focal point of the interior. The continuous entablature, the placement of the giant order of Corinthian pilasters and the off-axis siting of the subsidiary chapels create an architecturally unified fabric that sweeps the eyes around the walls and back to the altar, much as Bernini had earlier made an organic unity of the interior architecture of the Raimondi Chapel (1640-47) at S Pietro in Montorio and of the Cornaro Chapel (1647-52) in S Maria della Vittoria (see §1(iii) above).

(iii) Secular buildings.

Although Bernini was intermittently involved in designing additions to or advising on the restoration of existing palaces, such as the Palazzo Barberini and the Collegio di Propaganda Fide, he designed only three major secular schemes: the Palazzo Ludovisi (begun 1650; now the Palazzo di Montecitorio), the Palazzo Chigi (begun 1664; now the Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi; see ), both in Rome, and the ill-fated project for the Palais du Louvre, Paris. The first two buildings were a decisive and influential break with the astylar Roman Renaissance palace type represented by the Palazzo Farnese. The Palazzo Ludovisi, designed for the family of Innocent X, consists of a massive 25-bay block divided into five units that meet at obtuse angles. The centre and end units project slightly and are articulated with giant Corinthian pilasters at their corners, running through the two principal storeys above a semi-rusticated basement. Although it was not completed until after 1691 by his former assistant Carlo Fontana, its main features follow Bernini's intentions. Bernini elaborated this theme of a giant pilaster order over a strong and simple basement with greater success at the smaller Palazzo Chigi. This time he used pilasters between all the window bays of the main block; the slightly recessed subsidiary blocks are astylar. The once centrally placed entrance portico has two free-standing Tuscan columns. The particularly sensitive relationship of the parts was, however, destroyed in 1745 when Nicola Salvi extended the façade to twice its original length.

The Louvre project was commissioned in 1664 at the height of Bernini's fame by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, in his capacity as Louis XIV's Surintendant des Bâtiments. It was intended to provide a structure to close off the fourth (east) side of the famous Cour Carrée, its outer façade to be the monumental entrance to the palace complex. Bernini produced a series of designs, the final two developed from his Roman palazzi. Although work was begun on foundations while Bernini was in Paris from June to October 1665, the resolutely Italianate quality of his final design, its lack of internal convenience and the intrigues of the French court architects and their supporters meant that it was quietly abandoned when Louis XIV turned his attention away from Paris to his château at Versailles. (For a discussion of Bernini's plans for the Louvre in the context of those provided by French architects see Paris, §V, 6(ii).)

(iv) Piazza S Pietro.

Gianlorenzo Bernini: Piazza S Pietro, 1656-67, aerial view; Photo credit:…Bernini's greatest architectural achievement is the Piazza S Pietro, begun in 1656 under Alexander VII and completed in 1667. The construction of the square and colonnade was an undertaking of immense proportions and complexity. As Domenico Bernini wrote, 'the eye was no less stupefied at viewing the square and colonnade upon entering than at the end by the Cathedra Petri'.

In transforming the small existing piazza, Bernini was expected to cater for several functions. First, he had to provide a suitable space for the throngs who assemble for the papal blessing delivered from the Benediction Loggia above the main portal of the façade. He had to allow a view of the window in the Vatican Palace on the north side of the square from which the pope gives his Sunday blessing. It was also necessary to create a monumental, dignified approach to St Peter's, one that expressed its special status as the primary church of Christendom. On a more practical level, passageways protected from the elements were required for ceremonial processions as well as for pedestrian and coach traffic. Bernini's solution was to regularize the narrow, sloping space immediately in front of the church-the so-called piazza retta-and to demolish the medieval and Renaissance buildings impinging upon the planned site. He laid out a vast oval area, its long axis parallel to the façade of the basilica and with the great obelisk erected by Sixtus V at the centre. This space was defined and framed by two immense, curved, free-standing colonnades, each composed of four rows of Doric columns. Viewed from the square, these lines of massive columns produce a powerful sculptural effect capped by the legions of travertine saints populating the balustrade and silhouetted against the sky.

This architectural complex creates a ceremonial space of the utmost grandeur. Moreover, the purposely low profile of the colonnade arms, their heavy proportions and linkage to the outer edge of St Peter's stressed the vertical thrust of Maderno's façade with its lighter Corinthian columns and so helped to diminish the sense of excessive width caused by the addition of two bays as foundations for the unrealized bell-towers. Bernini was well aware of this problem, for under Innocent X he had proposed to separate the towers from the façade, a solution too radical to be seriously entertained. Instead he conquered this problem optically. Acutely aware of how space affects the visitor's perception of a work of art, Bernini sought here more than ever to draw the visitor in to a dramatic experience. In his original plan for the square he envisaged a third, free-standing section of colonnade, at the now open end of the piazza, to close off the arms and to screen the visitor's view upon his approach. After traversing the narrow, dark streets of the Borgo and penetrating the colonnade, the visitor would enter the piazza and view the vast, light-filled open expanse framed by monumental columns curving towards the majestic façade of St Peter's. This arm was never built, and the broad avenue created in 1937 with its vista towards the Tiber distorts Bernini's intention that the colonnades should 'embrace Catholics to reinforce their belief, heretics to reunite them with the Church, and agnostics to enlighten them with true faith'.

As part of this rearrangement of the space in front of St Peter's, Bernini also constructed a new ceremonial staircase leading to the Vatican Palace. The Scala Regia (1663-6; see Rome, §V, 14(iii)(a) and fig.) was conceived as an extension of the northern corridor of the piazza retta at the level of the portico of the basilica. Confined both by the ancient site of the entrance to the palace and by the encroachment of the existing buildings, Bernini once again solved by optical and scenographic means problems that could not be solved spatially. The 90° turn that has to be made between the portico and the first flight of steps in the monumental staircase is made into a spectacular scenic feature by the placing of the equestrian statue of Constantine the Great, which confronts the visitor on entering the vestibule. The long staircase is broken halfway up by a landing flooded with light, and twin rows of columns, free-standing at the bottom of the stair, attached to the walls and diminished in size at the top, effectively disguise the steepness of the ascent and the fact that the walls converge.

II. Working methods and technique.

While in Paris in 1665 Bernini addressed the members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture concerning the theory and practice of art. He noted: 'In my early youth I drew a great deal from Classical figures; and when I was in difficulties with my first statue, I turned to the Antinous as to the oracle' (see Fréart de Chantelou). Indeed, Domenico Bernini reported that as a youth his father drew the ancient sculpture in the Vatican every day from early morning to sunset for three years, resulting in a prodigious number of sketches. For Bernini, antique sculpture was the touchstone of artistic beauty and perfection. The Apollo Belvedere, Laokoon, Antinous and the Belvedere Torso (all Rome, Vatican, Mus. Pio-Clementino) were among the masterworks of antiquity that shaped his aesthetic. This dependence is consistent throughout Bernini's career from the most easily identifiable references in his early works-the Apollo Belvedere in the Apollo and Daphne, the Borghese Gladiator (Paris, Louvre) in the David and the Capitoline Hercules and the Hydra (Rome, Mus. Capitolino) in the Pluto-to the totally transformed allusions to the Laokoon in the Chigi Chapel Daniel and to the Antinous in the Angel with the Superscription.

Bernini's assimilation and transformation of Classical sculpture was but a part, though an essential one, in a complex creative process in which, as Baldinucci noted, 'Bernini strove with everything in him to make resplendent all the conceptual beauty inherent in whatever he was working on.' That process, at once deliberate and intuitive, involved certain stages: 'first comes the concept, then reflection on the arrangement of the parts, and finally giving the perfection of grace and tenderness to them…. He said that each of these operations demanded the whole man and that to do more than one thing at a time was impossible.'

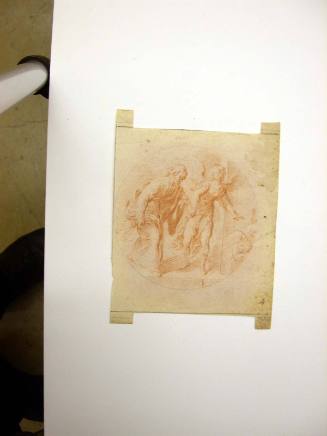

The formulation of the concept usually meant beginning with an analysis of various ideas in numerous preparatory drawings and bozzetti. Only a few of what must have been countless numbers of these drawings and models survive, but they clearly demonstrate the nature and intensity of Bernini's working method. The most important groups of drawings are in the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, the Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig, and in Rome at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and the Gabinetto delle Stampe. There is a notable collection of bozzetti in the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA. The drawings-primarily pen, chalk, or pen over chalk-are remarkable for their freshness and vitality, recording with bold, spontaneous lines the essence of a figure or architectural detail. A whole sheet might be covered with rapid studies, such as those for the top of the St Peter's baldacchino (red chalk and pen and brown ink over chalk on grey paper; Vienna, Albertina), or a series of drawings examining a pose might be produced on separate sheets, such as those for the statue on the Neptune Fountain at the Palazzo Estense at Sassuolo, near Modena (black chalk on white paper; Windsor Castle, Royal Lib.). Once Bernini arrived at a final conception, he proceeded to analyse various parts of the figure, drapery and spatial or compositional elements in intermediate sketches, as with the series for St Longinus (red chalk on buff paper; Düsseldorf, Kstmus.).

Similarly, Bernini's bozzetti testify to his extraordinary creative energy. Joachim von Sandrart, when he visited Bernini's studio, reported that he saw no fewer than 22 bozzetti for the colossal statue of St Longinus (possibly including that now in the Fogg Art Museum). Unlike earlier Renaissance sculptural practice, in which highly finished bozzetti were used as models from which the final statue in marble or bronze was copied, Bernini's were handled like his drawings, as quick sketches to test a particular pose or specific detail. As Bernini's thoughts for a statue were developed in successive clay studies, the models did not necessarily become more polished and refined. Nor is there any indication that Bernini ever used full-sized models to copy the final work. When such models were employed-as with the great clay figures (Rome, ex-Mus. Petriano) of the Fathers of the Church and angels for the Cathedra Petri-they were used to test the effect of the statue in its intended location.

The existence of proportional scales incised in the bases of several bozzetti, including that (Cambridge, MA, Fogg) for one of the kneeling angels on the altar of the Blessed Sacrament at St Peter's, seems to indicate that Bernini worked on the marble block directly, measuring from the bozzetto to increase size, but never mechanically pointing off or copying the model as earlier sculptors had done. With the bust of Louis XIV Bernini amazed the King by putting aside the drawings and bozzetti that he had so carefully prepared and audaciously carving the portrait directly in the marble. Bernini explained that the models served only to introduce into his mind the facts he needed to portray; when he was ready to carve the marble, the bozzetti and drawings were neither necessary nor desirable. Such preliminary works might, indeed, detain him from reaching his goal, which was to produce a work of art that was not similar to the models but to the truth. Bernini remarked, 'I don't want to copy myself but to create an original.'

Bernini occasionally produced highly finished drawings and models, so-called presentation pieces. Among them are a design (pen and brown ink with wash on cream paper; St Petersburg, Hermitage) for the altar of the Blessed Sacrament at St Peter's and a terracotta model (Bassano del Grappa, Mus. Civ.) for the equestrian statue of Louis XIV. Such works were used to obtain project approval from the patron or as guides for assistants in the preparation of full-scale statues. Bernini could undertake the vast array of ambitious projects that came to him only with the aid of numerous subordinates-sculptors, masons, bronze founders, chasers, gilders, stuccoists, painters and draughtsmen. His principal sculptor assistant during the 1620s was giuliano Finelli, who helped with certain portions of the Apollo and Daphne. With the commission for the baldacchino Bernini's studio immediately expanded; for the rest of his life it was a beacon, drawing Italian and foreign sculptors to Rome to assist with seemingly endless commissions. Fundamental to the organization of the workshop was Gianlorenzo's brother (3) Luigi Bernini, who was not only a sculptor but also an engineer who invented much of the heavy equipment necessary to accomplish the great undertakings. Among Bernini's more regular sculptor assistants were Giuseppe Mazzuoli and Giuseppe Baratta. Andrea Bolgi made the models from which the bronze angels for the baldacchino were cast. Giulio Cartari, who was responsible for some of the figures on the Ponte S Angelo, was his most trusted assistant in later years, while his son Paolo Bernini was also in the workshop. The painters who worked under Bernini's direction are mentioned above (see §I, 2 above); his architectural assistants ranged from the young Borromini (see §I, 1(ii) above) to Carlo Fontana and Mattia de' Rossi, of whom the last mentioned accompanied Bernini to France. Despite the divergence of talent, style and personality that such a workshop arrangement presupposed, Bernini was able to organize and supervise his workforce by use of bozzetti and drawings to ensure the stylistic integrity of the final products.

III. Character and personality.

No artist before or since Bernini created as many sculptural projects on such a large scale. The scope of his achievements was matched by the dynamic power of his personality. Biographical sources present a man of boundless, concentrated energy totally devoted to his work. Contemporaries knew him as fiery and passionate with the stern visage of an eagle. His gaze could be of a terrifying intensity. Quick-tempered and easily inflamed, he defended himself, as Baldinucci reported, by responding 'that the same fire that seared him more than others also impelled him to work harder than others who were not subject to such passions'. An indefatigable worker, Bernini was able to spend up to seven hours at a time carving marble, showing stamina that his younger assistants could not sustain. He remained 'so steadfastly at his work that he seemed to be in ecstasy, and it appeared from his eyes that he wanted his spirit to issue forth to give life to the stone' (Baldinucci). The great esteem in which he was held is further exemplified by the great figures of Church and State who were drawn to him; Urban VIII considered him 'a sublime artificer, born by Divine Disposition'. Although he was not given to abstruse learning or theoretical speculation, Bernini could be charming, witty and adept in the diplomatic niceties of the papal court. He came to be accepted as an equal in the exalted world of popes and princes and, like Michelangelo, was admired as the rarest of men.

Bernini's comic genius was manifest not only in his caricatures (see §I, 2 above) but in his theatrical writings. Beginning in the early 1630s he wrote more than 40 comedies, which he staged, usually in his own house during carnival, using his family and assistants as actors. These popular works, of which only one, found untitled and known as The Impresario, has survived (see Beecher and Ciavolella, 1985), delighted and amazed the audience through their satirical references to contemporary personalities and by their miraculous stagecraft: Bernini's theatre, like his art, made the audience active participants in the drama.

Bernini's religious sculptures were public professions of his private faith. From the beginning of his long and happy marriage to Caterina Tezio in 1639 his religious beliefs intensified. He attended mass each morning, taking communion twice a week, and for 40 years he prayed at the Gesù every evening. He discussed theological matters with Jesuits and Oratorians and practised the spiritual exercises formulated by Thomas à Kempis in The Imitation of Christ. He prepared himself for death through the 15th-century tract Ars moriendi, firmly adhering to his deep faith in Christ's redemptive power. An engraving after his design, showing the crucified Christ hovering over a sea of blood, was placed at the foot of his deathbed.

IV. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

From the time of his appointment as architect of St Peter's in 1629, Bernini exerted tremendous influence and power. For almost half a century he was the virtual artistic dictator of Rome, a situation that earned him the admiration of most, but the enmity of others. To many of his contemporaries he was, in the words of Cardinal Lazzaro Pallavicini, 'not only the best sculptor and architect of his century but, to put it simply, the greatest man as well'. Yet the very factor that ensured Bernini's reputation-the seemingly perfect fusion of artistic genius and spiritual conviction for the exaltation of the faith-centred religious ideals of his age-made its decline inevitable. The waning of the papacy as a secular power coincided with the rise of empiricism and the Age of Enlightenment. By the mid-18th century, reason and scientific inquiry, though not displacing theology, had seriously weakened its previously supreme position. The spirituality of the Ecstasy of St Teresa appeared as false to the rational enlightenment mind as its style seemed unnatural. Bernini and the artists of the Rococo were excoriated by the exponents of a new aesthetic that sought to purge art of illusionistic devices, exuberant emotionalism and 'licentious' freedom by returning to a simple, noble style rooted in antiquity.

Following the Neo-classical theories of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, such writers as Francesco Milizia came to regard Bernini in sculpture, Pietro da Cortona in painting and Borromini in architecture as 'a plague on taste, a plague that has infected a great number of artists' (Dizionario delle belle arti, 1798). According to this view, in rejecting antiquity by giving free reign to his imagination, Bernini was considered to sacrifice correctness for brilliance, to distort form, to seduce the eye, to introduce error and licence and to abandon beauty. His transgression was not only artistic but also ethical, for, in violating the Classical ideals of simplicity and restraint in favour of sensuous appeal, Bernini subverted art's high moral purpose.

Bernini's reputation remained in near total eclipse for most of the 19th century. However, the growth of art history as an intellectual discipline gradually freed Bernini and the newly defined Baroque age from the moral and aesthetic prison of the Neo-classical writers. Jacob Burckhardt and Heinrich Wölfflin were among the historians who opened the way towards a dispassionate analysis of Bernini's century, one in which his genius was recognized, though seen in conflict with an unworthy age. Italian scholars also began to look at Bernini in a new light, breaking free of critical bias and probing the archives for records of Bernini's career. In 1900 Stanislao Fraschetti's life of Bernini appeared, the first detailed, scholarly account of Bernini's career and a cornerstone of modern Bernini studies.

In the 20th century art historians continued the process of reintegrating Bernini's art into the context of his time, a re-evaluation of the Baroque age having created a fuller understanding of the 17th century as a complex period of competing stylistic trends. The chronology of his oeuvre has been clarified in several documentary studies. The work of Heinrich Brauer and Rudolph Wittkower on Bernini's drawings (1931), Wittkower's fundamental monograph (1955), Kauffmann's study of the figural compositions (1970) and Lavin's Bernini and the Unity of the Visual Arts (1980) are among the publications that have helped to restore Bernini's reputation and an image of the artist at one with his time.

Michael P. Mezzatesta and Rudolf Preimesberger. "Bernini." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T008287pg2 (accessed March 22, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665