Edward Colonna

Edward Colonna

1862- 1948

Edward Colonna, an Art Nouveau designer, had a rich and stimulating early career but success and publicity eluded him, and he was relegated to an obscure life. Colonna, a pseudonym for Klonne, was born May 11, 1862 near Cologne, Germany, to Karl Edouard Klonne, his father and his second wife, the former family servant Henriette Quack. Edward was the first of three children to his father's second family. At the age of 15, he left home to study architecture, reputedly in Brussels, Belgium.

In the later part of 1882, Colonna left Europe for the United States and settled in New York City. He soon found employment with Louis C. Tiffany, one of the country's leading decorating consultants. After a few years, he left Tiffany and took a position with the New York architect Bruce Price. It was through Price that Colonna found a new position as chief designer for the Barney & Smith Manufacturing Co. of Dayton, Ohio. Barney & Smith specialized in the manufacture of railroad cars and built Mid-Continent's MLS&W coach. At that time, they were the second largest such company in the nation, and boasted a workforce of 1500 men.

Barney & Smith had contacted Bruce Price on several previous occasions, not only for interior designs in some of their railroad coaches, but also as architect for one of their corporate officer's local residence. Perhaps knowing Colonna through his work with Bruce Price, he was hired and began his new job at Barney & Smith in September 1885.

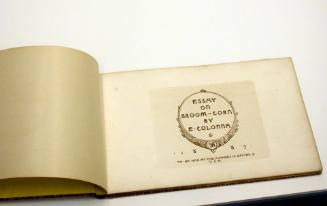

While working at Barney & Smith, Colonna also established a social and artistic relationship with other prominent local citizenry and expanded his interior design work with them. The high point of his career in Dayton was the publication of two small books containing some of his early designs. The first book was titled, Essay on Broom Corn and the second was Materiae Signa, Alchemistic Signs of Various Materials in Common Usage. The Essay designs are considered boldly innovative and were unlike so much of Colonna's work from this period which is considered conservative in design. Some of Essay's designs were translated into designs used in the MLS&W #63 coach's interior.

Colonna left the employment of Barney & Smith at the end of October 1888. He returned to New York City where he completed papers to become a naturalized citizen of the United States. However, his stay in New York was brief as he continued on to Montreal, Canada, where he established his own office. One of his major clients was the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Canadian Pacific was a big customer for Barney & Smith passenger cars and it is assumed he worked closely with their management while working for Barney & Smith. He continued to design the interior of Canadian Pacific's parlor and sleeping cars, some of which were still being built by Barney & Smith. However, Colonna's main emphasis returned to architectural design, his early training. He was commissioned to design many of Canadian Pacific's western sector railroad stations and also obtained remodeling projects and commissions among the Canadian Pacific's management and other Canadian businessmen.

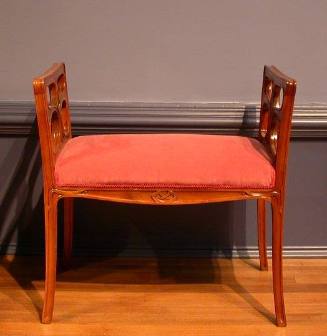

The railroad expansion era was starting to fade by the late 1890s and Colonna's commission work with the Canadian Pacific was at an end. By 1897 Colonna was associated with S. Bing and his celebrated Parisian store, Maison de l'Art Nouveau. Bing had earlier established himself as a scholar, connoisseur, and merchant of refined art to the world aristocratic class. His store lent its name to the "new art style" being introduced to the world at that time. The Art Nouveau movement was defined as "long sinuous curves of vegetal inspired forms" and Colonna's design style was viewed as being harmonious with the Art Nouveau movement as evidenced in his earlier Essay on Broom Corn. Colonna was initially charged with the design of jewelry and decorative glassware, later advancing to furniture design and other large-scale objects while working for Bing. His work received several prizes and an enthusiastic reception major exhibits sponsored by Bing. The artist's international reputation was firmly established and his employment with Bing insured.

However, prizes and endorsements do not always make a successful artisan or business. Bing's empire began to disintegrate due to a lack of a buying public and L'Art Nouveau closed its doors in 1903. With the demise of L'Art Nouveau, Colonna returned to Canada taking up residence in Toronto. He remained active in interior decoration over the next twenty years with some minor commissions and assignments but it was evident that his work was now being driven by his customers' demands rather than his own ideas. Also during this time he traveled frequently to France, England, Italy, Germany, and New York City as he became increasingly engaged in selling antiques, these various enterprises provided Colonna with adequate prosperity.

In 1923 at the age of 61, Colonna retired to Nice in southern France. His health was beginning to fail as paralysis was starting to affect his legs. However, his energy was great and his savings too meager for his retirement. He returned to his antiques business and also acted as an agent locating items for various museum collections.

His health continued to deteriorate and by 1928 his legs were completely paralyzed and he was confined to bed. As an invalid, he now fell back on his talent as a designer in attempting to provide a continuing income for himself. He resorted to drawing monograms and carving alabaster bowls, vases and, candlesticks. He attempted to exhibit and sell these items through some of his old business acquaintances. Recognition continued to elude him and on October 14, 1948, he died at the age of 86, and was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave in Nice, France.

In 1970 an original MLS&W #63 car was donated to Mid-Continent Railway Museum (www.midcontinent.org) and museum personnel prepared the car for preservation and eventual restoration. Fortunately, enough of all the original Colonna interior has survived to make restoration to original appearance possible. A successful two-year fund raising campaign was concluded on September 1, 2000 to raise $350,000 needed to restore the car to its original configuration. Work began in November 2000. Two and a half years later, the restoration is complete, and the car is now on display at the museum.

From http://www.macklowegallery.com/education.asp/art+nouveau/Artist+Biographies/antiques/Decorative+Artists/education/Edward+Colonna/id/23

An exhibition of his work was organised by the Dayton Art Institute in 1984.