Image Not Available

for William Morris

William Morris

British, 1834 - 1896

Nevertheless, present in the sources named here are key concepts that act as lines of perspective and converge on a very substantive aesthetic theory in Morris's work, though—let it be added—his practice as an artist only partially reinforces what his verbal utterances say.

Another matter, essential to note in any discussion of Morris's aesthetic theory, is his commitment to socialism, beginning in 1883. This is not the place to detail the history of Morris's involvement with the nineteenth-century British socialist movement, an interest and activity lasting until his death in 1896, but it should be emphasized that socialist lecturing and writing were important parts of his life and career. As for his aesthetic theory, however, the significance of his socialism is more problematic. He had already, before 1883, expressed his strong preference for the decorative arts, calling them in an 1879 lecture “the art of the people,” and, in an 1880 talk, “the beauty of life,” contrasting the traditional decorative arts with the ugly luxury goods produced for the wealthy. What Morris's commitment to socialism did was enable him to confirm and articulate his strong belief by relating it to a broad historical view of the transformation of early European society into modern capitalist society, marked by its own class system. Already deploring the death of “the art of the people,” the crafts, he now tied their disappearance to the absorption of farm laborers and artisans into the urban factory centers and the manufacture for their consumption of cheap and shoddy goods.

Already disliking the art of the late Renaissance, the eighteenth century, and most of the nineteenth century, Morris now argued that all this bad art had been made to suit the degenerate taste of the wealthy, entrepreneurial middle classes, who produced nothing themselves but demanded that ugly luxury items be provided for their gratification, corrupting the artists thus employed. Socialism gave Morris a historical explanation of why the arts had declined and reinforced his commitment to the decorative arts, particularly as they were pursued in the precapitalist Middle Ages. The principles of the art of the Middle Ages, by definition decorative, expressive of the stonecutter, the illuminator, the weaver, became for Morris the principles on which to base a future art of a future socialist society.

Morris's preoccupation with the decorative arts led to a number of reiterated admonitions delivered in lectures to art students and to general audiences. A central one—an aesthetic commandment—is “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful and think to be beautiful,” and it defines one class of objects capable of expressing beauty. Although he does not spell out the implications, the grounding in functionalism sets limits on the material forms that can be regarded as beautiful. Pottery, for example, is included, but ornamental objets d' art presumably are not. As for painting, the admonition avoids the question of how to regard a picture on canvas. Morris's ambivalence toward easel painting in theory comes down on the positive side when he could regard a painted canvas as a wall decoration, as living architecture, which for Morris was the mother of all the other arts. Nevertheless, he strongly preferred walls to be decorated with wallpaper or simply whitewashed, and the potential decorative function of an easel painting in a nineteenth-century home remains in his discourse just that—a potential, and an ignored one. It should be added, however, that Morris had strong opinions, both positive and negative, about paintings in museums; he strongly supported art museums—indeed, museums in general—as repositories of the past, and he was also very much in favor of museums as sites for education. Nevertheless, the fact that most of the particular references to painting in his lectures and letters have to do with Pre-Raphaelite works is at once an expression of true admiration, of loyalty to friends who were Pre-Raphaelite painters (and who had also been praised by Ruskin), and a measure of how limited Morris's interest in oil painting was.

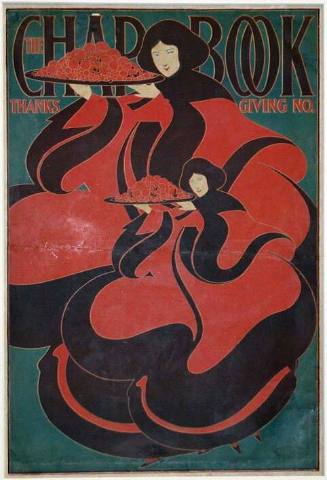

Another rule for Morris is that all forms be conceived in the mind of the artist before being committed to paper or other material, and that outline—his synonym for form—be definite; as an implicit corollary, outline should be regarded as prior to color, however important color may be in larger historical terms. Morris affirms the linear and rejects the painterly mode of creating images in color; and image in a discussion of Morris must be regarded as including such terms as design and pattern. There is also a clear antecedent in Morris's sinuous wallpaper designs based on stylized natural forms—flowers, vines, and leaves—to the approach to drawing of the aesthetic movement at the end of the century, particularly Aubrey Beardsley's sinuous lines creating “unnatural” human forms. Line, moreover, is for Morris the basis of mimesis, and mimesis is much involved for him in what art should do. There is a continuous admonition in his lectures to students, and indeed in letters to artists employed as illustrators of Kelmscott Press editions of Morris's own work, to “get it right”; and right invariably means depicting correct proportion in the human figure, rendering in accurate detail a building facade, and observing Ruskinian “truth to nature” in the depiction of leaves, flowers, and other vegetation. Yet, there was also in Morris's aesthetic, as in Ruskin' s, a keen sense of pattern as abstraction from the natural—though still with heavy emphasis on outline—usually demonstrated in his practice as designer of wallpaper and chintz patterns.

All of the above is important for assembling Morris's aesthetic, but the most challenging and profound of his aesthetic ideas is drawn from—or leads to—his social and political egalitarianism, confirmed and reinforced by his commitment to socialism in 1883. All work done with pleasure is art, he asserts. This is a striking challenge to one of his other positions, and a contradiction of another. Pleasurable work that produced objects intended for the home, but useless there, would presumably not qualify, although Morris gets around this by asserting in his essays that it is impossible to get real pleasure from producing useless objects. As for outright contradiction, Morris advised several petitioners for his encouragement that it takes a special “gift” to draw patterns or the human figure, although he added—again, strikingly—that the pleasure of enjoying art was equal on any scale of human values to the pleasure of making art. Be it also said that nowhere is he on record as discouraging anyone from embroidery or textile weaving—if the fingers are nimble enough.

Carefully outlined forms; a commitment to functionalism, with emphasis on the decorative arts in the home; an implicit grounding of aesthetic experience in the material; mimesis in modern painting and in illustration; a faith that creativity is universal—that pleasure in work inspires the creative imagination in everyone: all of these inform Morris's aesthetic. These are constants, but as noted, the contradiction, variation, and extension are also there. The belief that the production of art depends on a “gift” contradicts the belief that creativity is universal, but Morris's compensatory assertion that one person's pleasure in enjoying a work of art is equal to another's pleasure in making a work, opens up an aesthetic of receptivity. In this respect, Morris's position is congenial, it should be added, with Walter Pater's viewer-centered aesthetic, but shifts away from Ruskin's stress on the “truth” inherent in a work of art and accessible only to a cultivated sensibility. Of course, when Ruskin generalizes about art he has high art in mind, and so for that matter does Pater, whereas Morris, when he generalizes, is thinking of the decorative arts (and at times of poetry). Nevertheless, the force of Morris's position is to democratize Pater's onlooker philosophy of art rather than to search, as Ruskin does, for essence.

As a poet, Morris wrote lyrics, brief dramatic verse, and long narrative poems. The models for his lyrics were John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley; for his brief dramatic poems, Robert Browning (to some extent); and for the long narratives, Geoffrey Chaucer's work and the Icelandic poetic Eddas. For poetry, more than any other art, Morris denied that there was for him anything that could be called an aesthetic theory. Early in his career, while he was still an undergraduate at Oxford, occurred the famous incident in which he read his first poem to a group of friends, was praised by them, and answered, “Well, if this is poetry, it is very easy to write.” His utterance epitomizes a lifelong attitude toward the writing of verse. Nevertheless, the assertion that he resisted naming an aesthetic of poetry should be qualified by observing that he strongly preferred rhymed to unrhymed verse and that as a writer he preferred composing long narrative poems to short, lyric ones. Although he hardly had praise for any poet other than Chaucer, his enthusiasm for The Canterbury Tales equaled what he felt for his other true love in verbal art, the novels of Walter Scott, Charles Dickens, and Alexandre Dumas the elder.

What Morris does enjoy in poetry is “incident,” a term that instantly links together his ideas about verse, prose narrative, and illustrations for books—for the illuminated medieval manuscripts and early printed books he loved, and for those he produced and had illustrated at his Kelmscott Press. Significantly, his “truth to nature” in art is restricted, like Ruskin' s, to the representation of vegetable nature. “Naturalism,” as a literary phenomenon, he disliked (as did Ruskin). The great irony is that while he followed Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite painters in denouncing Sir Joshua Reynolds's assertion that painting should idealize the human face and form, Morris created only idealized protagonists for his romances (including News from Nowhere, his socialist romance). “Truth to nature” meant only truth to the forms and details of leaves, flowers, and the exterior world in general.

Arguably, however, and indeed as Jerome McGann has demonstrated, Morris's concern with the typography and page layout of his poems and romances, his revolutionizing the printing arts at the end of the nineteenth century through his own Kelmscott Press, demonstrate the profoundest kind of “naturalism” in literature of all. It demonstrates—indeed, constitutes—a recognition that books are material objects, and that pleasurably experiencing their visual and tactile materiality is an essential aspect of the aesthetic experience of reading, not an adjunct to it.

Nevertheless, there remains in Morris's practice and in his lectures on art some division along the visual/verbal line: partially different approaches to realism for each. The difficulty persists in attempting to find a perspective from which we might perceive a unified aesthetic theory in his lectures and his practice as an artist. Standing in the way is the difference between his insistence on the useful in the decorative arts (“have nothing in your home you do not know to be useful …”) and the “useless” in poetry, epitomized by Morris's self-description in the prologue to The Earthly Paradise (a long narrative poem written early in his career) as “the idle singer of an empty day” (although he later wrote socialist poems, too). Along the same dividing line, form comes before color in the making of patterns and images in general, but a setting for his prose romances that is vague, seemingly medieval, but only seemingly. Only as a reader, as author of The Defence of Guenevere (his early lyric and dramatic poems), and as translator and adapter of Icelandic sagas did Morris experience in verbal art a pleasure in characteristics akin to those he required for the decorative arts and book illustrations: sharply defined incidents against clearly rendered backgrounds; a minimum of sentiment; and, in the saga translations and adaptations, depictions of survival in a world in which humans and nature are treacherous—that is, a depiction of “truth” to both external and human nature: a kingly version of naturalism in characterization set against a sharply defined background.

Putting aside these achievements, which, given the many attributes of his narrative writing and the extent of it, represent in total only a few aspects of his verbal art, it can be said that Morris strove for directness and vigor in all his art but achieved these largely in his decorative designs for wallpapers, chintzes, and borders for pages and illustrations for the Kelmscott Press volumes. For the most part, the verbal arts in reality were for him a letting go rather than a screwing himself up to pitch: writing poetry and prose romances was for Morris an escape from the rigor of “form.” Of course, his verbal compositions have their own forms. There is in them an air of ease and a feeling of verbal plenitude. These are determining characteristics, as valid of assessment as aesthetic characteristics as any other. But the forcefulness that one feels when looking at his visual patterns is not there.

There is, too, Morris's view of himself as a writer. If it is at variance with his practice, it is nevertheless essential to add this view to the information from which we derive his aesthetic theory. Perhaps because Pater in the late nineteenth century had introduced into aesthetic discourse the term “euphuism” in a laudatory way, Morris was at pains to assert his freedom from “euphuism,” expressing pleasure to Theodore Watts-Dunton for declaring him guiltless of it (as well as of “didacticism” and “the curse of rhetoric”), in a review of one of Morris's prose romances, The Wood beyond the World.

This romance is lush and eloquent and moves at an easy pace, and indeed is characterized by what some might regard as archaic and therefore artificial language. Morris, however, would deny this, and the denial would be plausible. A mimetic absorption into his own work of the language of medieval romance was natural for him. All told, Morris regarded himself as writing “naturally,” as doing analogously in prose what he and Ruskin believed painters should do—remain “true to nature”—and what he believed pattern designers (like himself) should begin by doing, however flattened and thus abstracted the forms in the pattern derived from nature ultimately were.

There is finally, despite difficulty, a large, embracing view enabling a perspective that discloses a coherent aesthetic theory. Morris was the epitome of his own seemingly divided aesthetic made whole. Whereas for him people to an extent were divided for aesthetic purposes into the categories of those capable of making art and those capable only of enjoying it as onlookers or users, he reunited the roles in his own actions as both designer and writer of romances. The pleasure he took in designing and in writing shared an etiology. They were both preceded by the pleasure Morris took in seeing the medieval patterns and reading the medieval tales he often used as a basis for his own art. Observer and maker, he testified that pleasure for him meant any relationship at all to art, and that both visual design and verbal incident in his work resulted from the pleasure of recalling design and incident in the art of the past and the pleasure of then transforming them—and thus making art that was new. “Pleasure” in making is Morris's substitute for “inspired vision,” “genius,” and even for imagination, when this last is, in use, too closely allied with genius, a term Morris never employed to express his admiration for any artist's ability and achievement. The modesty of pleasure's claim lays the ground of an egalitarian aesthetic in the verbal and the visual arts and in a way that reaches for a simultaneous embrace of both.

Yet, still impeaching Morris's democratic aesthetic is the distinct feature that characterizes his own art: the vigor of his designs and of some passages at least in his narrative poems, long and short. It creates the tension, the presence of compressed energy, so characteristic of his designs and of his best poetry—and not only energy but aggressive energy, a fact about himself and his art that he did not see. It is the aggressive energy within his work that pulls together his verbal art, in which undercurrents of violence or longing underlie seemingly languorous episodes, and his decorative work, in which the vigor of his lines makes immanent a will that to an extent bends nature—the lines of natural objects—to itself and that thus substitutes creative vision for truth to nature. Finally, this powerful stylizing impulse, profound in its implications, and among other things replacing “truth to nature” with a calm violence toward it, puts Morris's aesthetic practice into the Aesthetic movement, which he ignored or reproved, but helped to found, and in which he continued as a presence recognized by fellow members of the movement. That Morris was both a socialist and an inspiration to the aesthetic movement, particularly to its younger members in the 1890s, is not a contradiction. It is an invitation to see the prophetic quality of his vision: his understanding that aesthetic sensibility is part of the definition of the human and that a political reconstituting of society to realize more fully human life must mean, whatever else it means, reconstituting opportunities for expression and gratification of that sensibility.

Kelvin, Norman. "Morris, William." In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, edited by Michael Kelly. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/opr/t234/e0366 (accessed May 1, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

American, School: Color-field painting, 1924 - 2010