Karel Appel

Born Amsterdam, 25 April 1921; died Zurich, 3 May 2006.

Dutch painter, sculptor, designer, printmaker and writer. He was first encouraged to paint by an uncle, who gave him a set of paints for his 15th birthday, and he also took painting lessons. From 1940 to 1943 he studied at the Rijksakademie of Amsterdam, where he became friendly with Corneille. His earliest works recalled the painting of George Hendrik Breitner; during World War II, however, he began to paint with a more vigorous palette, with a clear interest in German Expressionism and above all in the work of van Gogh. There was a turning-point in Appel’s style c. 1945 when he found inspiration in the art of the Ecole de Paris and in particular of Matisse and Picasso. This influence remained visible in his work until 1948, for example in a series of plaster sculptures that he made at this time. From 1947, his completely personal, brightly coloured universe of simple, childlike beings and friendly animals populated gouaches, oil pastel drawings, painted wood sculptures and, gradually, oil paintings. His sense of humour comes to the fore in grotesque assembled pieces and wooden reliefs and paintings such as Hip, Hip, Hooray (1949; London, Tate).

In July 1948 Appel, Constant and Corneille were among the founders of the Experimentele Groep in Holland; in Paris in November of the same year Appel was also one of the founders of the international Cobra movement. The contacts resulting from this movement, especially with the Danish members, encouraged Appel to continue in the primitivistic vein in which he had already embarked. His most important source of inspiration during this period was children’s art. His work aroused both indignation and revulsion in the Netherlands. A mural, Children Asking Questions (for illustration see W. Stokvis: Cobra: An International Movement in Art after the Second World War; New York, 1988; fig.), which he painted in the cafeteria of the former city hall in Amsterdam in early 1949, was hidden behind a layer of wallpaper for ten years because the public found it intolerable.

At the end of 1950 Appel moved to Paris. In 1952, with better painting materials at his disposal (thanks to the support of the writer and art promoter Michel Tapié), his work became more fluent. Somewhat rigid, thinly applied areas of colour linked by a few thick lines had dominated his compositions since 1950, making them strongly reminiscent of the work of Miró, but from 1952 to 1960 he increasingly adopted a passionate style in which colour and line fused into an agitated mass of paint so as to take precedence over the motifs. Animals and human beings were still recognizable in these paintings, although they assumed an unchained, demonic character. The turbulence of the paint and the riot of colour gradually controlled enormous areas of canvas, for example in From the Beginning (1961; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.). From 1956 Appel painted portraits such as César (1956; Belfast, Ulster Mus.), some of them large scale, and a series of female nudes, both in the same manner. When he travelled to New York for the first time in 1957, he painted jazz musicians such as Miles Davis and Count Basie; for Appel, as for many of the former members of Cobra, jazz had always been an important source of inspiration. He divided his time from then on between New York and Paris, and from 1964 he lived also at the castle that he had acquired in Molesmes, in central France.

From the mid-1950s Appel began to acquire a considerable international reputation. Martha Jackson exhibited his work regularly from 1954; Appel also had one-man shows in Paris at Studio Facchetti, and at Galerie Rive Droite from 1956. Willem Sandberg provided him with powerful support from the Netherlands, and, through Sandberg’s intervention, Appel took part in a series of international group shows, also having retrospectives of his work in prominent museums in various countries. In 1960 he received the international Guggenheim award for his painting Woman and Ostrich (1957; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.). The following year the Dutch journalist Jan Vrijman made a film about Appel, De werkelijkheid van Karel Appel (The reality of Karel Appel), in which the left-handed artist was filmed attacking enormous canvases as if possessed; the film was accompanied by music composed by Appel and the jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie.

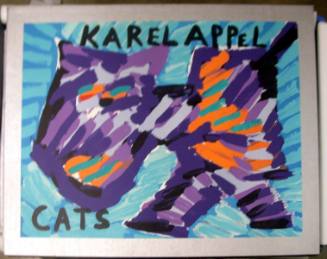

In France in summer 1961, Appel produced a series of sculptures from olive trunks, which he painted in brilliant colours. In 1963 he was briefly influenced by Pop art and incorporated all sorts of objects, including plastic toys, in his paintings, for example Motherhood (1963; priv. col., see 1970 exh. cat., p. 43). Around 1966 he began to make an increasing number of wooden reliefs, which soon became free-standing objects, such as Three Figure Triptych (1967–8; Amsterdam, Stedel. Mus.). These works, with their cut-out and therefore strongly outlined forms, which he then superimposed and painted, and the childlike motifs, which he chose for the objects that he produced, recall Appel’s artistic vocabulary during the period of Cobra’s existence. He extended this style c. 1968 to polyester and in the early 1970s to aluminium. From the mid-1950s he also produced reliefs and free-standing pieces in ceramic. While he preferred acrylic paints for his canvases in these years, he began again to use oil paints in 1976, at which point he attempted a conscious renewal of his style. To this end he spent some time in painting compositions in thick parallel strokes; his subjects included masklike faces, cats and still-lifes.

Around 1980 Appel rediscovered the turbulent expressionistic language with which he had reached a high point in the second half of the 1950s. Working in turn in his studio in New York and from 1979 in his house in Monaco, he began to paint, in a muted palette, first a series of Windows, followed by Crimes (e.g. Crime I, 1980; priv. col., see 1987 Bristol exh. cat., p. 23) and a varied assortment of dramatic subjects, with human figures as the central theme. Some of these works recalled contemporary German Expressionism, the so-called ‘Neue Wilde’, and revealed, in the case of certain landscapes, his love for the art of van Gogh. He also produced sculpture in the form of windmills in earthenware combined with other materials. In 1986–7 Appel made sculptures of Standing Nudes from large Polaroid photographs and wood (e.g. Standing Nudes nos 2–4; artist’s col., see 1987 New York exh. cat., pp. 12–13).

Appel was famed for his flamboyant self-promotion and was tireless in his exploration of new media; after World War II he even wrote poetry. He received many large-scale commissions, including mural paintings, sculptures, stained-glass windows, carpets and tile pictures, which were produced either by Appel or by assistants. He also wrote the plot and designed the scenery for the ballet Can We Dance a Landscape?, performed at the Opéra, Paris, in 1987.

Willemijn Stokvis. "Appel, Karel." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T003457 (accessed May 3, 2012).