Jacques de Gheyn, II

Born Antwerp, 1565; died The Hague, 29 March 1629.

Draughtsman, engraver and painter. He was taught first by his father and then from 1585 by Hendrick Goltzius in Haarlem, where he remained for five years. By 1590–91 de Gheyn II was in Amsterdam, making engravings after his own and other artists’ work (e.g. Abraham Bloemaert and Dirck Barendsz.). There he was visited several times by the humanist Arnout van Buchell [Buchelius]. De Gheyn received his first official commission in 1593—an engraving of the Siege of Geertruitenberg (Hollstein, no. 285)—from the city and board of the Admiralty of Amsterdam. In 1595 he married Eva Stalpaert van der Wiele, a wealthy woman from Mechelen. From 1596 to 1601–2 he lived in Leiden, where he began collaborating with the famous law scholar Hugo de Groot [Grotius], who wrote many of the inscriptions for the artist’s engravings. During this period he also began working for Prince Maurice of Orange. In 1605 de Gheyn was a member of the Guild of St Luke in The Hague, where he remained until his death. Once he had settled in The Hague, de Gheyn’s connections with the House of Orange Nassau were strengthened. Among other commissions, he designed the Prince’s garden in the Buitenhof, which included two grottoes, the earliest of their kind in the Netherlands. After the Prince’s death in 1625, de Gheyn worked for his younger brother, Prince Frederick Henry.

Although originally a Catholic, de Gheyn seems to have turned to Calvinism and gradually abandoned orthodox Catholic themes. His subject-matter was also influenced by his contact with the newly established university at Leiden. He never travelled to Italy and, apart from an interest in Pisanello, there is little evidence in his work (except in his garden designs) of the influence of Classical antiquity or the Italian Renaissance, both of which were so attractive to many of his northern contemporaries. Much information about both de Gheyn II and de Gheyn III is provided in the autobiography of Constantijn Huygens the elder, secretary to Frederick Henry. Jacques II is also mentioned by van Mander, for whom he worked as a reproductive engraver. Van Mander wrote of de Gheyn II, among other things, that he ‘did much from nature and also from his own imagination, in order to discover all available sources of art’. Indeed, some of his images are completely fictitious, while others are based on reality. Often his works are a mixture of these two components.

1. Drawings.

Altena (1983) catalogued 1502 drawings by de Gheyn II, including designs that survive only in prints. For his drawings de Gheyn used a quill pen and dark brown ink with white heightening, black or red chalk or brush and wash. Those intended to be reproduced as prints are often indented with a metal stylus for transfer on to the plate. Before 1600 his style was clearly dominated by the influence of Goltzius, whose small silverpoint and metalpoint portraits on ivory-coloured tablets de Gheyn imitated, although he used a yellow ground and rendered his sitters more gracefully and dynamically than the simple and unadorned portraits of Goltzius. The majority of de Gheyn’s portraits date from before 1598. He was particularly skilled in his use of both the pen and the brush. While his free, sketchy studies in pen and ink are usually made without wash, his preparatory drawings for engravings, such as those for the Exercise of Arms (c. 1597; various locations, see Altena, 1983, nos 346–459), commissioned by Prince Maurice of Orange and published in The Hague in 1608, are elaborately washed and sometimes heightened with white. Initially de Gheyn’s drawings imitated Goltzius’s engraving style, as can be seen in the Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Hat in his Hand (Berlin, Kupferstichkab.), which may, according to Altena, represent Matheus Jansz. Hyc. De Gheyn’s draughtsmanship, like that of Goltzius, belongs to the tradition of Dürer, Pieter Bruegel the elder and Lucas van Leyden; it is also related to the undulating graphic style of Venetian woodcuts by Titian and Domenico Campagnola.

In his landscape drawings de Gheyn was also influenced by Paul Bril and Hans Bol. These seem to have been based mostly on his imagination and contain no evidence of direct visual contact with nature. In some cases, such as the grand Mountain Landscape (New York, Pierpont Morgan Lib.), which reflects a type of alpine landscape traditionally associated with Pieter Bruegel, it is difficult to distinguish reality from fantasy. De Gheyn did not make realistic landscapes in the style of Goltzius, but occasionally accurate elements of the Dutch landscape appear in the background of his narrative scenes with figures. An exceptional case is his Landscape with a Canal and Windmills (Amsterdam, estate of J. Q. van Regteren Altena, see Altena, 1983, iii, p. 59), which he made after the drawing by Hans Bol (1598; London, BM).

Around 1600 de Gheyn gradually began to dissociate himself from the influence of Goltzius. His pen lines are more fluent, sometimes grow quite wild and tend to have a recognizable curly rhythm. The extensive use of hatching and crosshatching reflect his skill as an engraver. He rarely used red chalk, preferring black chalk and occasionally the combination of chalk with pen and ink, as in the Studies of a Donkey (c. 1603; Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.).

De Gheyn II also produced carefully coloured drawings on parchment in a naturalistic style. In these he would often use watercolour as well as bodycolour, with occasional highlights in gold. A splendid example is the Old Woman on her Deathbed with a Mourning Cavalier (1601; London, BM). This miniaturist technique can be best compared with the English ‘Arte of Limning’, described in a treatise by Nicholas Hilliard, and it is possible that, through Constantijn Huygens, de Gheyn may have known these colourful miniatures. A magnificent album from 1600–04 (Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.), once in the possession of Rudolf II, consists of 22 watercolour drawings on parchment, executed in this miniaturist technique. Among the almost photographic representations of natural objects are flowers, mostly roses, insects and also a crab and a mouse. The studies are part of a long-standing tradition of natural history illustrations, of which Dürer, Joris Hoefnagel and Georg Flegel were key exponents. The scientific value of the album leaves lies in the fact that they represent rare examples or newly cultivated varieties of flower. The famous scholar Carolus Clusius is thought to have been de Gheyn’s adviser in these matters. As in other works, symbolism apparently plays an important role in this album.

De Gheyn also represented the female nude in drawings. Two of the seven known examples are certainly after the same model (Altena, 1983, ii, nos 803 and 804); the others seem more or less realistic in conception. Together with similar works by Goltzius, they are among the earliest nudes in Dutch art. Another iconographic innovation by de Gheyn was the realistic portrayal of domestic scenes, as in the drawing of Johan Halling and his Family (1599; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and the Mother and Son Looking at a Book by Candlelight (c. 1600; Berlin, Kupferstichkab.). Such genre scenes were not to be painted regularly on a larger scale in Holland until the 17th century.

A number of de Gheyn’s drawings are allegorical, although often unclear or complex, for example the Allegory of Equality in Death and Transience (1599; London, BM) and the related engraving (Hollstein, no. 98), for which the 16-year-old Hugo de Groot wrote the caption. Also allegorical in meaning is the Archer and Milkmaid (c. 1610; Cambridge, MA, Fogg), a preparatory study for a print that carries the legend ‘Beware of him who aims in all directions lest his bow unmasks you’.

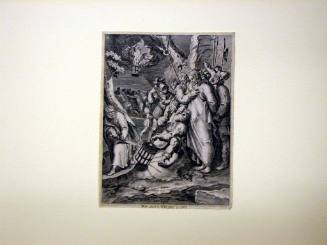

Perhaps de Gheyn’s most original inventions iconographically were his ‘spookerijen’ (‘spooks’), the drawings of sorcery and witchcraft. The meaning of, for example, the Two Withered Rats (1609; Berlin, Kupferstichkab.) or of his drawings of monstrous, crawling rats remains a mystery. The enormous Witches’ Sabbath (Stuttgart, Württemberg. Landesbib.) is reminiscent of the work of Hans Baldung and of contemporary literature on witchcraft. His drawings of strange knotted tree trunks, surely imaginary rather than realistic, are related to the grotesque ornamental style, for the curious, gnarled bark seems to contain hidden figures. There are also some drawings that seem to fall outside any particular iconographical category; they are strange, fantastical scenes, sometimes bordering on the magical, such as the Naked Woman in Prison (Brunswick, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Mus.), the meaning of which, if any, is unclear.

2. Prints.

The 430 engravings and etchings catalogued by Hollstein include prints after de Gheyn’s own designs as well as those of other artists. From 1585 until the end of the 16th century he imitated Goltzius’s burin manner in his engravings; the lines cut into the copperplate vary in thickness, with the density of the hatchings and crosshatchings suggesting passages of light and dark as well as volume. In some cases dots intensify the density of crosshatchings. Before Goltzius’s departure for Italy in 1590, de Gheyn was already using this engraving technique, known as the ‘zebra effect’, in his series of Standard-bearers (1589; Hollstein, nos 144–5). A proof state of one of these plates (Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) shows de Gheyn’s masterly handling of the burin. He also used a finer engraving technique with short hatchings, strokes and dots, as can be seen in the portrait of the numismatist Abraham Gorlaeus (1601; Hollstein, no. 313); this old-fashioned type is reminiscent of the portraits of learned humanists at the time of Hans Holbein.

As in the drawings, after c. 1600 a gradual change took place. De Gheyn’s engraving style became more mature, with lines more evenly spread over the whole of the copperplate. His exceptional talent is seen at its height in the Fortune-teller (Hollstein, no. 105), datable shortly after 1600. He more or less abandoned engraving after 1600, but this print can only have been made by him. The tree is certainly based on one of his preparatory tree studies. He depicted relatively few biblical or mythological subjects in his engraved work, preferring, instead, to concentrate on series depicting contemporary events, for example the Battle of Turnhout (1594; Hollstein, no. 286) and his striking large print of Prince Maurice’s Land Yacht (1603; Hollstein, no. 63).

The most important change after 1600 was that de Gheyn began to experiment with etching, a technique that was not fully exploited in its own right until the work of Rembrandt in mid-century. Even though with etching it is not possible to vary the thickness of lines, de Gheyn’s etching style hardly differs from that of his engraving. According to Burchard, there are two etchings certainly by Jacques de Gheyn II: the Farm at Milking Time (Hollstein, no. 293), which looks like a Venetian-style woodcut, and the Happy Couple (Hollstein, no. 97), which is remarkable for its effective division of light and dark, achieved by, among other things, a fine use of stippling. However, these attributions are not universally accepted. Konrad Oberhuber attributed the Happy Couple to de Gheyn III ( Jacques Callot und sein Kreis, exh. cat., Vienna, Albertina, 1968–9, pp. 67–8); and Altena (1983) described the Farm at Milking Time as ‘Anonymous after J. de Gheyn II’. They may have been made after drawings (both Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) by Jacques de Gheyn II. The engravers Jan Saenredam and Zacharia Dolendo were both pupils of de Gheyn II.

3. Paintings.

Like Goltzius, Jacques de Gheyn II did not take up painting until c. 1600, about the time he stopped engraving. Of the 47 works catalogued by Altena (1983), at least 21 survive, while the rest are known from documents and old sale catalogues. The figure paintings are reminiscent of the drawings but lack the conception behind the large academic nudes painted by Goltzius, as well as his ‘burning’ reddish-brown colour. The unnaturally posed Seated Venus (c. 1604; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) is closer to the Mannerist style of Bartholomäus Spranger than to examples from antiquity or the Renaissance. De Gheyn’s history paintings have not been extensively studied. The best known is his painting of Prince Maurice’s White Horse (1600; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), the artist’s first commission from the Prince. There are also a few paintings with obscure subjects, such as the Woman in Mourning Clothes Lamenting over Dead Birds (Sweden, priv. col., see Altena, 1983, ii, no. P16).

De Gheyn’s best-known paintings, the vanitas still-lifes and flower-pieces with butterflies, caterpillars, shells and the like, which are painted in the Flemish tradition, are of better quality. The earliest, the still-life Allegory of Mortality (1603; New York, Met.; see [not available online]), bears the explanatory caption: hvmana vana. In such works as the Bouquet in a Glass Vase (1612; The Hague, Gemeentemus.), the roses are almost withered and recall the emblematic motto ‘rosa vita est’. The unsigned painting on copper of a Vase of Flowers (ex-Brian Koetser Gal., see Altena, 1983, ii, no. P31) is a special case: all the flowers recur in the Paris album of miniatures. His flowers, mostly roses and tulips, are all on the verge of withering and are painted with a dynamism not found in freshly cut flowers; this could also be an allusion to the transience of life. This stylization of nature often recurs in the artist’s oeuvre.

E. K. J. Reznicek. "Gheyn, de." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T031910pg1 (accessed May 8, 2012).