André Masson

Born Balagne, 4 Jan 1896; d Paris, 28 Oct 1987.

French painter, draughtsman, printmaker and stage designer. His work played an important role in the development of both Surrealism and Abstract expressionism, although his independence, iconoclasm and abrupt stylistic transitions make him difficult to classify. Masson was admitted to the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts et l’Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Brussels at the age of 11. Through his teacher Constant Montald, he met the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916), who persuaded Masson’s parents to send him to Paris for further training. Masson joined the French infantry in 1915 and fought in the battles of the Somme; he was gravely wounded, and his wartime experiences engendered in him a profound philosophy about human destiny and stimulated his search for a personal imagery of generation, eclosion and metamorphosis.

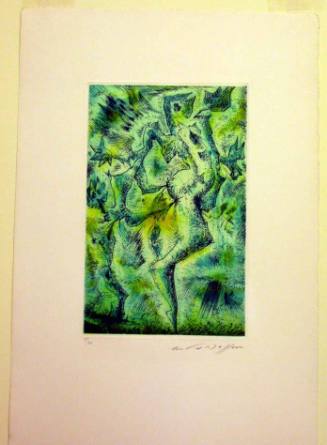

Masson’s early works, particularly the paintings of 1922 and 1923 on a forest theme (e.g. Forest, 1923; see Leiris and Limbour, p. 93), reflected the influence of André Derain, but by late 1923 he had moved away from Derain towards Analytical Cubism. His first solo exhibition, organized by Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler at the Galerie Simon in Paris (1923), attracted the attention of André Breton, who purchased The Four Elements (1923–4; Paris, priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., p. 102) and invited Masson to join the Surrealist group. Influenced by Surrealist ideas, both Masson and Joan Miró began experimenting with automatic drawing (for illustration see Automatism), and the Cubist imagery of Masson’s painting soon resonated with symbolic content. Two drawings were reproduced in the first issue of Révolution surréaliste in December 1924. By late 1929 the Cubist syntax of Masson’s paintings had become more schematic, the compositions more open, and the imagery developed from random ‘automatic’ gestures (see Automatism). By sprinkling coloured sands on canvas, prepared by drawing ‘automatically’ with glue, he was able to retain the spontaneity of the drawings, yet build a complex poetic imagery. One of the first, and most successful, sand paintings is Battle of the Fishes (1927; New York, MOMA), in which a primordial eroticism is revealed through an imagery of conflict and metamorphosis, poetically equating the submarine imagery with its physical substance.

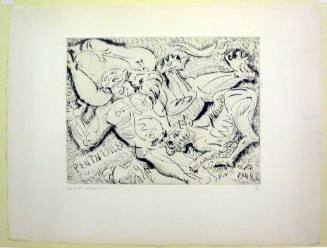

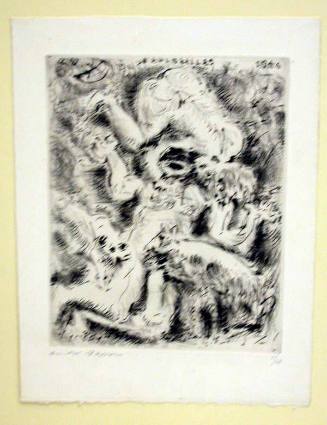

Between 1924 and 1929 (when Breton expelled Masson from the Surrealist group) the biomorphic abstractions of Miró and Masson dominated Surrealist painting. Masson spent much of the period between 1930 and 1937 in the south of France and in Spain. During this period he explored themes and subjects drawn from Greek mythology, Spanish literature and the Spanish Civil War. From 1931 to 1933 the theme of massacres prevailed and led to a series of violent, orgiastic drawings filled with sharp, jagged pen strokes (e.g. Massacre, 1933; ex-artist’s col., see Hahn, p. 15). A group of expressionistic scenes of ritualistic erotic killings based on Greek mythology followed. In 1933 Masson executed the drawings Sacrifices including The Crucified One, Mithra, Osiris and Minotaur (published as etchings, as Sacrifices, Paris, 1936) to accompany a text by Georges Bataille. That same year he completed the first of a group of stage designs and costumes for the ballet Les Présages, choreographed by Léonide Massine for the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo, followed by designs for Knut Hamsun’s La Faim (1939), the production by Jean-Louis Barrault (b 1910) of Cervantes’s Numance (1937) and Darius Milhaud’s Medea (1940), among others.

Masson’s return to Paris in 1937 and his reconciliation with Breton were marked by a move towards greater representation and deep illusionistic spaces in his art, perhaps influenced by the prominence of Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Yves Tanguy in the Surrealist movement at that time. Images of erotic violence and death mingle with mythological and literary themes drawn from ancient Greece and from Sigmund Freud’s writings on the dream and the unconscious, in Gradiva (1939; Knokke-le-Zoute, Casino Com.), Metamorphoses (1939; Paris, Gal. Ile de France) and other major paintings of these years. The myth of Theseus and the Minotaur provided the theme for numerous paintings and drawings and finally led Masson away from illusionism and back to a form of automatism in which the unity of the human and natural worlds is achieved through the process of drawing itself.

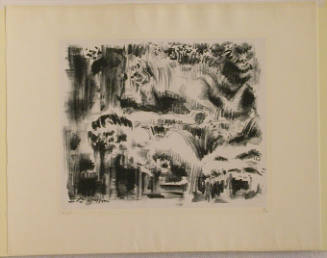

Automatism continued as the basis of Masson’s work during his years in New York during World War II. The series of telluric paintings, rich in the colours of the autumn landscape in Connecticut, where Masson was living at the time, including Meditation on an Oak Leaf (1942; New York, MOMA), Iroquois Landscape (1942; Paris, Simone Collinet priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., p. 164) and Indian Spring (1942; New York, Mr and Mrs William Mazer priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., p. 165), reveal a spontaneous and integrated relationship between colour, line and form. Leonardo da Vinci and Isabella d’Este (1942; New York, MOMA) can be cited as an important influence on Arshile Gorky’s move toward biomorphic abstraction in the early 1940s. Although direct influences are more difficult to determine, there are strong affinities with Jackson Pollock’s work of those years, which he may have seen at S. W. Hayter’s Atelier 17 where both artists worked in the 1940s.

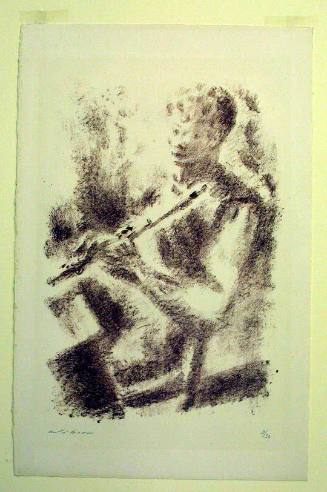

Masson returned to France in 1946, settling in Aix-en-Provence until 1955. In 1950 a series of his essays was published as Le Plaisir de plaindre (Nice). A series of trips to Italy from 1951 resulted in the album of colour lithographs Voyage à Venise (1952) and other works on the theme of the Italian landscape. Although Masson did not participate in the last major international exhibition of Surrealism (Paris, 1947), he was cited in the catalogue as one of the ‘Surrealists in spite of themselves’ (also included in this group were Picasso, Dalí and Oscar Domínguez). The paintings of the post-war period, however, reflect Masson’s growing interest in Impressionism, J. M. W. Turner and Zen Buddhism. Combining Impressionist style with Oriental technique and imagery, and drawing on his whole repertory of themes and techniques, as well as branching out into new areas opened up by his study of Zen, Masson abandoned chiaroscuro for all-over luminosity, soft transparent pastels and a personal and gestural calligraphy. A large retrospective exhibition with Alberto Giacometti in Basle in 1950 was followed, five years later, by the Grand Prix National.

Masson’s most important commission was his invitation from André Malraux to paint the ceiling of the Théâtre de l’Odéon in Paris (1965). Masson continued to divide his time between Paris and the south of France. The course of his work was marked less by stylistic unity than by his commitment to art as a poetic, philosophical and psychological exploration. His last work expanded the themes of transformation and metamorphosis that he began in 1922.

Whitney Chadwick. "Masson, André." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T055025 (accessed March 6, 2012).