Käthe Kollwitz

Born Käthe Ida Schmidt in Königsberg, Eastern Germany, to a middle-class family, Kollwitz had a liberal-minded father who encouraged her talent. In 1881, she took private art lessons with a copper engraver and in 1885, enrolled in the School for Women Artists in Berlin. From 1888 to 1889, Kollwitz attended the School for Women Artists in Munich, where she took etching courses, in addition to her university classes.

Two years after leaving the Munich school, she married Dr. Karl Kollwitz and moved to Berlin, where her husband treated primarily poor patients. In 1894, she received a prize from the German Art Exposition in Dresden for her etching cycle inspired by Gerhard Hauptmann's play The Weavers. By the beginning of World War I, Kollwitz was recognized as one of the most prominent German graphic artists and had already been involved with various social, political, and artistic organizations, among them the Berlin Secession and Simplicissimus, a satirical magazine. In October 1914, her son, Peter, was killed in battle. His death fueled Kollwitz's anti-war sentiments, and her work became increasingly strong in its pacifist stance. In 1918, the Social-Democratic newspaper Vorwärts published her response to the poet Richard Dehmel's call for all able-bodied men and boys to die for the Fatherland. She quoted Goethe's words, "seed corn must not be ground," implying that the nation's future depended on its youth, which must not be squandered in a war of attrition.

Kollwitz was appointed as the first female professor and member of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts in 1919. Also during this year, she created the woodcut Memorial to Karl Liebknecht in honor of the murdered Spartacist leader. In 1921, she created the poster Help Russia for the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe, whose other members included Otto Dix, George Grosz, and Heinrich Zille. Kollwitz produced many images depicting the hunger and misery of the 1920s, as well as anti-war posters, among them Never Again War!

In 1928, she became the director of the master studio for graphic arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin. Throughout these years, she worked on a memorial to Peter, a sculpture of two mourning parents, which in 1932 was placed in the military cemetery in Belgium. Although Kollwitz was not harassed by the National Socialist Party as much as other artists (such as Max Beckmann), she was forced to resign from the Academy of Fine Arts, in part as a result of signing an "Urgent Appeal" to unite socialist and communist leaders against fascism. Another run-in with the Nazis occurred in 1936, when the Gestapo threatened her with deportation to a concentration camp due to an interview she had granted Izvestia, the Soviet newspaper. However, Kollwitz was never deported.

In 1942, the year her grandson was killed in action, Kollwitz created her last lithograph, Seed Corn Must Not Be Ground. She died in 1945, shortly before the signing of the armistice.

Biography from Savvy Collector:

Käthe Kollwitz began her life as Käthe Schmidt, daughter of a well-to-do mason, in 1867 in East Prussia. Her father arranged for her to have private art instruction at the age of 14. In 1884 he sent her to study at an art school for women in Berlin, followed by study in Munich. This was very progressive for the time period.

She married Dr. Karl Kollwitz in 1891, with whom she later had two sons. They moved to an impoverished section of Berlin where his practice served its needy residents. As a result, she was constantly surrounded by hardship, hunger and death and developed a strong social conscience, which is intensely reflected in her work.

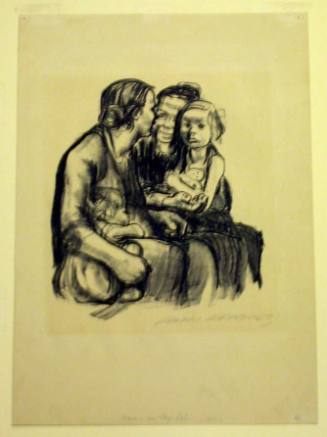

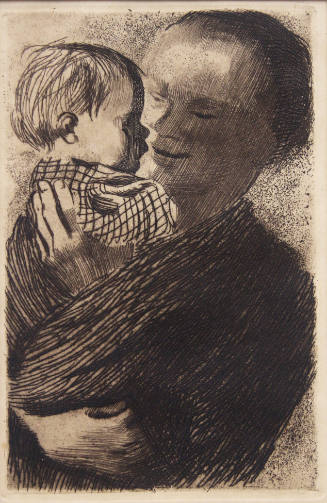

Käthe Kollwitz was influenced by the work of Max Klinger and Edvard Munch. She explored and depicted emotionally charged subjects, including death, war and injustice, in a desire to move ordinary people to action. Her images are often dark and oppressive representations of the revolts and uprisings of contemporary relevance. In contrast, she also captured tender loving moments between mothers and their children.

As a result of the unkindest cut of all, the death of one of her sons in World War I, Kollwitz suffered extreme bouts of depression for the remainder of her life. She is quoted as having said that “Drawing is the only thing that makes life bearable.

”Best known for her etchings, Käthe Kollwitz also explored lithography, woodcut and sculpture. In 1919, she was appointed the first female professor at the Prussian Academy. However, due to her art and political beliefs, she was forced to resign in 1933, when Hitler rose to power. Three years later, some of her works were removed from museums and galleries and she was forbidden to exhibit. In 1943, her home and much of her artwork was destroyed in a Berlin air raid.

Kollwitz was evacuated to Dresden. There she died in 1945 at age 78, without seeing an end to the Second World War, that took the life of a grandson.

Biography from AskART:

The following text was written and submitted by Jean Ershler Schatz, artist and researcher of Laguna Woods, California:

Kaethe Kollwitz was born in Koenigsberg, East Prussia in 1867. The family name was Schmidt, and they were cultivated, middle class people who considered a talent to be a duty. Her art education began in 1881; she began studying with Rudolph Mauer, a local engraver. At seventeen, she enrolled in the School for Women Artists in Berlin. Her early studies, which reveal a developing social consciousess, depicted workers engaged in manual labor. In 1885, she became engaged to a medical student, Karl Kollwitz, who was also a member of the Social Democratic Party. Over the next fifty years, her husband's practice exposed her to an even wider range of suffering and tragedy.

Kollwitz first studied etching in 1889-90 in Munich, the artistic center of 19th century Germany. She was greatly influenced at the time by Max Klinger's imaginative etchings. She was impervious to contemporaries such as Cezanne, Picasso, Matisee, and Emil Nolde. She pursued an art aimed at voicing the suffering of the people. She remained, throughout her distinguished career as a graphic artist, outside a political party.

She was well-known by the time she was thirty. Her final years were not happy, however, for her life was completely disrupted by the fascism sweeping Germany in the late 1930s. After the Gestapo threatened her with arrest, she wore a vial of poison around her neck. She was forbidden to teach and her works, placed on a list of degenerate art, were banned from exhibition. Her son Peter died in Flanders during World War I; she was struck to the bone and used the occasion for one of her most moving protests against war.

During World War II she was evacuated to Moritzburg, near Dresden. In 1943 a bomb fell on her home in Berlin, destroying early paintings, prints and plates. In April 1945, only a few days before the Armistice, Kollwitz died. She was seventy-eight.

Today the street on which Kollwitz lived in Berlin has been renamed in her honor and a park graces the spot where her house once stood.

Sources:

Radcliffe Quarterly, December 1991

Catalogue of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Time Magazine, June 21, 1948 and May 7, 1956

http://www.askart.com/askart/artist.aspx?artist=9001530