Andy Warhol

(b Pittsburgh, PA, 6 Aug 1928; d New York, 22 Feb 1987).

American painter, printmaker, sculptor, draughtsman, illustrator, film maker, writer and collector. After studying at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh from 1945 to 1949, he moved to New York and began working as a commercial artist and illustrator for magazines and newspapers. His work of the 1950s, much of it commissioned by fashion houses, was charming and often whimsical in tone, typified by outline drawings using a delicate blotted line that gave even the originals a printed appearance; a campaign of advertisements for the shoe manufacturers I. Miller & Sons in 1955-6 (Kornbluth, pp. 113-21) was particularly admired, helping to earn him major awards from the Art Directors Club.

Warhol continued to support himself through his commercial work until at least 1963, but from 1960 he determined to establish his name as a painter. Motivated by a desire to be taken as seriously as the young artists whose work he had recently come to know and admire, especially Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, he began by painting a series of pictures based on crude advertisements and on images from comic strips. These are among the earliest examples of Pop art. The first such works, for example Water Heater (1960; New York, MOMA) and Saturday's Popeye (1960; Mainz, Landesmus.), were loosely painted in a mock-expressive style that parodied the gestural brushwork of Abstract Expressionism. Those that followed, however, such as Before and After 3 (1962; New York, Whitney), one of several paintings based on advertisements for plastic surgery, were phrased in a deliberately inexpressive style of painting characterized by hard outlines and flat areas of colour.

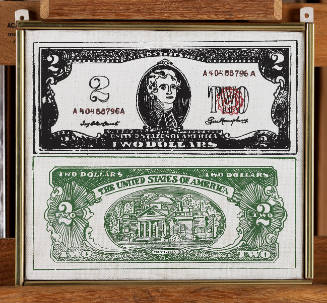

In their calculated exclusion of all conventional signs of personality, in their apparent rejection of invention and in their blatant vulgarity these first Pop works were brutal and shocking, designed to offend the sensibilities of an audience accustomed to thinking of art as an intimate medium for conveying emotion. Warhol extended these concerns through techniques that gave his images a printed appearance, including the use of stencils, rubber stamps and hand-cut silkscreens, and in his choice of subject-matter. He was drawn to the shocking images of tabloid newspapers, as in 129 Die in Jet (Plane Crash) (see fig.), to money (in a series of screenprinted paintings representing rows of dollar bills) and to the denigrated products of consumer society, including Coca-Cola bottles and tins of Campbell's Soup (e.g. One Hundred Cans, 1962; Buffalo, NY, Albright-Knox A.G.).

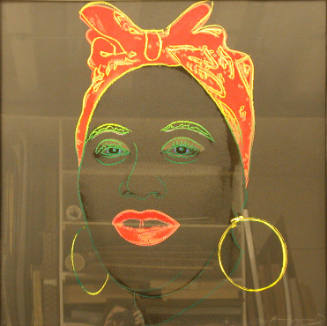

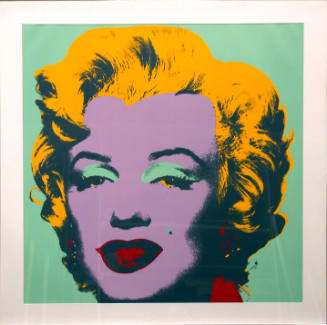

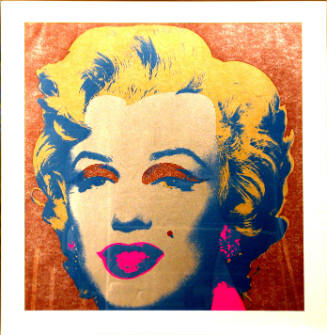

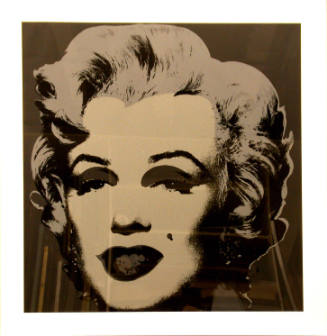

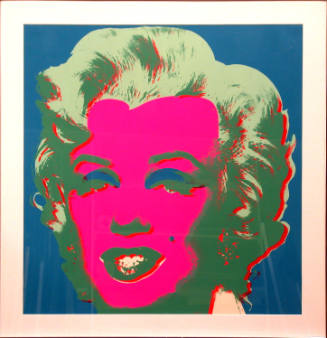

From autumn 1962 Warhol's paintings were made almost exclusively by screenprinting photographic images on to backgrounds painted either in a single colour or in flat interlocking areas that corresponded approximately to the contours of the superimposed images. In these works, executed with the help of assistants in the studio that he called The Factory, he succeeded in removing his hand even more decisively from the canvas and in challenging the concept of the unique art work by repeating the same mechanically produced image until it appeared to be drained of all meaning. Among the most successful of these were portraits of glamorous film stars such as the recently deceased Marilyn Monroe, whose masklike face acquires an iconic quality in works such as Marilyn Diptych (for illustration see Pop art), and gruesome images of car crashes and other daily disasters as seen in photographs reproduced in mass-circulation newspapers, such as Green Disaster Ten Times (1963; Frankfurt am Main, Mus. Mod. Kst). He also applied his ideas about art based on mass production in a witty installation of sculptures at the Stable Gallery in New York in 1964, replicating supermarket cartons to their actual size by screenprinting their designs on to blocks made of plywood (e.g. Brillo Boxes, 1964; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig).

During a visit to Paris for an exhibition of his work in 1965, Warhol announced his intention to retire from painting in order to devote himself to the experimental films that he had begun making in 1963. Although he continued to paint and contributed significantly to the growing interest in limited edition prints through works such as the Marilyn portfolio of ten screenprints published in 1967 (Feldman and Schellmann, p. 39), he became increasingly involved with other media. Films such as Empire (black and white, 8 hours long, 1964), an unbearably prolonged shot of the Empire State Building against a darkening sky, presented his aesthetic of boredom in its most extreme and provocative form. His multi-media events under the banner of The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, which combined the live music of The Velvet Underground rock band with projections of film and light, subjected the audience to a sensory experience that combined the energy of popular culture with the concerns of performance art.

After an attempt on his life in 1968, Warhol distanced himself from the drug addicts, transvestites and other unconventional types who had formed his entourage and became associated primarily with the wealthy and fashionable members of high society. With the exception of particular series such as his portraits of Mao Zedong (e.g. Mao, 4.44×3.47 m, 1973; Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), a topical subject chosen at the time of President Nixon's visit to China, he concentrated in the 1970s primarily on commissioned portraits printed from enlargements of Polaroid photographs. Deprived of the glamour of an immediately recognizable public figure, these frankly commercial works, such as Jane Lang (1976; Seattle, WA, A. Mus.), were seen by many as the mark of his artistic decline, although the income they generated enabled Warhol to celebrate his final self-declared transformation from commercial artist to business artist.

Among the most striking works of Warhol's prolific later production are a series of 102 Shadows (each 1.93×1.32 m, 1979; New York, Dia A. Found.), all screenprinted from a vastly enlarged photograph of a shadow cast by a painting in his studio, which were exhibited edge-to-edge as an installation that completely surrounded the viewer's field of vision. His Oxidation Paintings of the late 1970s (e.g. see MOMA exh. cat., pp. 350-51), made by urinating on a surface of copper paint, were equally experimental and came close to pure abstraction; seductively beautiful in their metallic sheen, they, too, contain an element of savage parody in their reinterpretation of the principles of 'all-over' composition ascribed to the paintings of Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock.

Warhol's work regained much of its lost spirit in the 1980s, thanks in part to the support of younger artists indebted to his example. After producing a group of collaborative paintings with Francesco Clemente and the American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88), he returned for the first time since the early 1960s to painting by hand. His last works included several hand-painted pictures on religious themes after Renaissance masters, such as the Last Supper (acrylic on canvas, 3.02×6.68 m, 1986; artist's estate, see MOMA exh. cat., p. 395), in which a version in outline of Leonardo's enduring interpretation of one of Christianity's most sacred events is partly obliterated by grossly enlarged logos of brand names. It is a fittingly ambiguous testament to an artist who was a devout Catholic but who maintained an equally strong reverence for the capitalist system that was so central to his subject-matter. He died as a result of complications following a routine gall-bladder operation. A service attended by more than 2000 people was held in his memory at St Patrick's Cathedral, New York.

Warhol was remembered by friends and associates as a compulsive shopper. The bulk of his extensive collection, which contained only a small amount of contemporary art amongst a great deal of jewellery and decorative art (especially Art Nouveau and Art Deco), Native American art and American folk art, was auctioned a year after his death. His published writings, characterized by the same tone of dead-pan naivety as his work, contain some of the most revealing insights into the attitudes that moulded his art. The Andy Warhol Museum, housing a large collection of his works from all periods drawn in large part from his estate, was inaugurated in Pittsburgh in May 1994. (Source: MARCO LIVINGSTONE, "Andy Warhol," The Grove Dictionary of Art Online, Accessed April 19, 2004 (Oxford University Press) http://www.groveart.com)