Image Not Available

for Jeff Koons

Jeff Koons

American, born 1955

Koons studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Maryland Institute College of Art, and in 1977 arrived in New York from where he became an art world celebrity. His studio has been an immense SoHo loft on the corner of Houston and Broadway in New York, and his work expresses his fascination with commercial packaging and children's toys. Running his studio like a corporation, he has 35 full-time assistants, each assigned to a different aspect of his output--sculpture and small and large-scale paintings.

The following is from the Los Angeles Times, March 28, 2001:

Can He Be Serious?

Known for his kitschy works, controversial artist Jeff Koons returns to painting with a more mature approach.

By SUZANNE MUCHNIC, Times Art Writer

"I've always looked at my art and what I do in a very moral way," says Jeff Koons, smiling sweetly as he surveys big, splashy, collage-like paintings in his exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills. That may be news to longtime observers of the New York artist, who is largely known for merging childish desires and adult passions in kitsch statuary. It's certainly the most shocking statement to be heard these days from the art world superstar who set off one outrage after another in the 1980s and early '90s, but then got stuck in a morass of personal problems.

Koons, 46, emerged as a conceptual sculptor who encased gleaming vacuum cleaners in plexiglass boxes and immersed basketballs in aquariums, then set critics' teeth on edge as he moved on to "Statuary," starring a stainless-steel casting of a blowup bunny. Next came his "Banality" series, crowned by a 6-foot gold-leaf ceramic likeness of Michael Jackson cuddling his pet chimpanzee Bubbles--"the largest porcelain knickknack in the world," as Times critic Christopher Knight put it.

Back then, Koons wasn't known for his modesty. His penchant for self-promotion and the fact that he supported himself as a Wall Street broker while breaking into the art world led to the perception that his road to stardom was greased by excesses of the '80s. His stock fell further in critical circles during the early '90s, after he married Ilona Staller, a Hungarian-born porn star known as La Cicciolina who served an improbable five-year term as a member of the Italian parliament (1987-92). Their alliance led to Koons' most scathingly reviewed series, Made in Heaven, which portrays the couple having sex in challenging positions and full makeup.

Koons and Staller had a son, Ludwig, in 1992, shortly before their marriage fell apart. They separated and agreed to joint custody of Ludwig, but Staller fled from New York to Rome with the baby. American courts later dissolved the marriage and awarded exclusive custody to Koons, but the child remains with his mother in Italy.

In the midst of this highly publicized mess, Koons' artistic ratings suddenly shot out of the gutter into the stratosphere when he unveiled Puppy, a 40-foot West Highland terrier made of live flowers on a wood and steel frame. Introduced in 1992 near Documenta--an international exhibition held periodically in Kassel, Germany, to which Koons was not invited--Puppy stole the show and walked off with rave reviews.

The success brightened a bleak period for Koons, but the cloud of his domestic and legal ordeal lingers. "I went through a terrible injustice in Italy because of my son," he says, getting back to the morality issue. "That experience really gave me a sense of responsibility to the public. I was losing my sense of humanity. Now, every day, I feel more and more responsible in the act of communicating and sharing and really trying to be as generous as possible as an artist."

Even Koons' most ardent critics concede that he is an enormously influential figure, but he has always appeared to be a mass of contradictions --fresh-scrubbed and sincere on the one hand, cynical marketing genius on the other. While he no longer claims to be creating "some of the greatest art being made now" or says he has "absolutely assumed the leadership of the art world," he is increasingly emphatic about his work's value to himself and others.

"Art is more important to me and gives me more enjoyment every day," he says. "I look at art as an activity based in philosophy and psychology and theology. It used to be the great communicator; the medium was used for propaganda or other ends. When it lost aspects of that power to the entertainment industry and other areas, it was able to return to more of a primal activity. And I love the primal."

Which is to say, in part, that Koons still revels in sexual innuendo, if not explicit imagery. "I'm always interested in sex; it is how our species survives," he says.

He hasn't given up imagery associated with childhood either. Still, "the dialogue here is more adult," he says of his new work. "The more cartoon-like, animated surface has been removed, so the work seems slightly more threatening or dangerous. Maybe there is not so much protection on the surface."

In his new work, Koons has gone back to painting, a skill he developed in his youth. But just as he designed statuary to be fabricated by technicians during his heyday, he now dreams up collage-style paintings that are meticulously painted by assistants.

The latest crop--at Gagosian--is part of his "Easyfun--Ethereal" series. Loaded with images of floating bikinis and hair, fragmented nudes, juicy food and idyllic landscapes, the paintings explore elusive, vaguely Surreal imagery in an airy style that blends one form into another.

"As an artist, the only thing I can do is trust in myself," he says of his creative process. "Different things catch my eye, so I go through a lot of source material--the world around me, magazines, anything that captures my attention. If something tells me it's interesting, I go with it."

With those gleanings, he creates collages on a Xerox machine and a computer, then plays with color and dissolves parts of the pictures. One favorite approach is to remove bathing beauties' bodies but keep their bikinis and hair.

"I think the effect is quite sexual when the bodies drop out," he says. "There's a sense of being able to pass through the body completely, and that kind of space is also very spiritual."

One painting, Runaway, is a bit like a tightrope, he says, pointing out the tension between opposing hues and references to a circus in fragments of an elephant and a set of showgirls' jewelry. In other paintings, he cites references to elements of other artists' works.

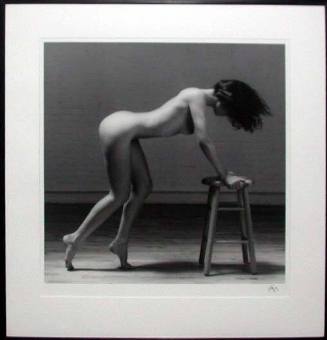

A sweep of chocolate paint curving over a crouching nude's back in Pam, for example, resembles a Jasper Johns' piece that incorporates a real broom and an arc of pigment left in its trail, he says. In Couple, a painting that merges a shipwreck with a calmer scene, the shape of a floating stocking reminds Koons of the mustache Marcel Duchamp applied to Leonardo's Mona Lisa in his irreverent 1920 work L.H.O.O.Q.

All this may appear to be a big change for Koons, but he says it's a natural outgrowth of sculptures that combined various figures, animals and objects. What's more, he says, collage is a vital art form that allows artists to mine the visual overload that surrounds them. "We see so much on a daily basis that we don't even think about it," he says. In fact, these fleeting images are familiar, and not only to the art crowd.

"I try to let viewers have some confidence in themselves," Koons says. "The things in my paintings are part of my own personal cultural history, but I don't think it is so different from everyone else's. We all know what the color blue was like when we were children, or what it meant to come across a favorite object, whether is was a porcelain or a teddy bear. I let people embrace their own history."

Person TypeIndividual