Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

French, 1824 - 1898

French painter and draughtsman. He is known primarily for his large decorative schemes depicting figures in landscape. Although he is generally regarded as a precursor of Symbolism, he was independent of any contemporary movement, and his works appealed to academic and avant-garde artists alike.

1. Life and work.

(i) Training and early work, 1824–60.

He belonged to a wealthy bourgeois family, and his father, Chief Engineer of the Mines, wanted him to enter the Ecole Polytechnique in Lyon. However, after obtaining his baccalaureate in Paris in 1842, Puvis was obliged to abandon this plan as a result of serious illness. When he had recovered, he spent several months at the Faculté de Droit, Paris, but left in 1846 to undertake a long trip to Italy, which stimulated his interest in art. Following his return in 1847 he studied for several months with Henri Scheffer (1798–1862), and in 1848 he undertook a second journey to Italy with the painter Louis Bauderon de Vermeron (1809–after 1870). He visited Naples, Arezzo, Venice and Rome, and his first known work, Allegory (Norfolk, VA, Chrysler Mus.), dates from this time: it bears the inscription Rome, 1848.

At the end of 1848 Puvis entered the studio of Eugène Delacroix, only a fortnight before it closed, and then joined Thomas Couture for a few months. Although Puvis is listed in the records of the Salon as the pupil of Scheffer and of Couture, in fact he accomplished his training largely through independent study with a live model, initially on his own and then from 1852 with Alexandre Bida (1813–95), Gustave Ricard and the engraver Victor Pollet (1809/11–82). Drawings in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon provide examples from this period of study.

Puvis exhibited for the first time at the Salon of 1850, with Dead Christ (Cairo, Gazíra Mus.), but in 1852 the three paintings he submitted were all rejected: Jean Cavalier Playing Luther’s Choral for his Dying Mother (Lyon, Mus. B.-A.), Portrait of M. de St O and Female Study. A series of paintings (mostly in the keeping of the families of his heirs) from this period demonstrates Puvis’s stylistic experimentation, extending from a realism in the manner of Honoré Daumier, for example in the Reading Lesson (1850; priv. col., see R. Jullian: ‘L’Oeuvre de jeunesse de Puvis de Chavannes’, Gaz. B.-A. (Nov 1938), p. 241, fig.), to a Romanticism in the style of Delacroix in Mlle de Sombreuil Drinking a Glass of Blood to Save her Father (1853; untraced, see Boucher, p. 10). He employed dark, violent colours and effects of light in the service of an expressionism that differs greatly from his future style.

In 1854–5 Puvis executed for his brother, Edouard Puvis de Chavannes (1821–63), the decoration of the dining-room at his country house, Le Brouchy, in Champagnat, Saône-et-Loire; it illustrates the theme of the Four Seasons, with a large central composition of the Return of the Prodigal Son (see exh. cat., pp. 37–9). Like all his decorative schemes and contrary to what has often been written, this is composed of painted canvas stuck to the wall; the only frescoes he produced are in the service-quarters at Le Brouchy, and these progressively deteriorated. Following this project, decorative paintings became Puvis’s main activity. In 1859 Puvis reappeared at the Salon with the Return from the Hunt (Marseille, Mus. B.-A.), which is a replica of one of the Le Brouchy panels.

(ii) Decorative schemes and easel paintings, 1861–98.

Pursuing his vocation as a decorator, in 1861 Puvis exhibited two large murals (each measuring 3.40×5.55 m), Peace and War, for which he received the second-class medal in the history section. Peace was purchased by the State, and, in order not to separate the two canvases, Puvis donated War. Still without any commissions, he produced the complement to this group, Work and Repose, which he exhibited at the Salon of 1863. Arthur-Stanislas Diet, architect of the Musée Napoléon (now Musée de Picardie) at Amiens, subsequently approached Puvis to obtain the two series for the museum. The first group was loaned by the State, and the second was donated by Puvis. He also executed eight allegorical figures to complete the group. Puvis’s first public commission, in 1864, came from the Musée Napoléon for Ave Picardia Nutrix (in situ). From then on Puvis exhibited regularly at the Salon. The critics were divided into two fiercely opposed camps: on the one hand, Jules-Antoine Castagnary, Charles Timbal (1821–80), Edmond About and Charles Blanc all reproached him for a lack of subject-matter and realism, for shortcomings in draughtsmanship and the poverty of his palette; on the other hand, Etienne-Jean Delécluze, Théodore de Banville (1823–91), Théophile Gautier and Paul de Saint-Victor (1825–81) praised his decorative approach and his striving to express an ideal world. Puvis’s career continued in a succession of commissions, although he possessed a personal fortune that allowed him to live independently without the need to sell his works.

The decorative art of Puvis is characterized by his desire not to pierce the wall but to respect its surface plane and to integrate the painted work with the architecture. He believed the colour should be neither violent nor hard; the material of the wall itself must be retained or, to be more precise, reconstructed. On the basis of this principle, Puvis never allowed himself to become constrained by a formula. Initially he was influenced by Pompeian art and 15th- and 16th-century Italian frescoes, particularly those by Piero della Francesca at S Francesco, Arezzo (c. 1454–66). He was also deeply and directly influenced by the paintings of Théodore Chassériau for the staircase of the Cour des Comptes in Paris (1844–8). Sensitive as well to contemporary art, he lightened his palette under the influence of the Impressionists. Puvis’s originality lies in the importance of the role he accorded landscape, set down in extremely simple, broad planes, in which the naked or draped human figure—defined with an economy of brushstroke and invested with an eternal nature—is at the same time a living being, the expression of an abstract idea and an element in the geometric composition. Through their attitudes, the stiff figures respond to one another and animate the surface; this is seen, for example, in Pleasant Land (1882; Bayonne, Mus. Bonnat), painted for the staircase of the Paris home of his friend Léon Bonnat.

The materials and style that Puvis employed are intentionally modest: opaque colours, muted shades, an absence of light and shade and minimum modelling. He prepared his canvases with plaster and glue, using blotting paper to remove excess oil from his paints, in a manner that increasingly imitated the appearance of fresco. Although Puvis obtained assistance for the placing of his large paintings, he was himself responsible for the execution of the works.

The iconographic subject-matter that Puvis tackled is more varied than would appear: historical in The Year 732: Charles Martel Delivers Christendom by his Victory over the Saracens near Poitiers and Having Withdrawn to the Convent of Sainte-Croix: Radegonde Shelters the Poets and Protects Literature from the Barbarism of the Age, Seventh Century (1870–75) for the staircase of the Hôtel de Ville at Poitiers; religious in a panel and triptych depicting the childhood of St Geneviève, surmounted by a frieze of saints (1874–8), for the Panthéon, Paris; and allegorical in the Sacred Grove, Vision of Antiquity, Christian Inspiration and The Rhône and the Saône (1884–6) for the staircase of the Musée des Beaux-Arts at Lyon and in Muses Welcoming the Genius of Enlightenment and other works (1895–6) for the staircase of the Boston, MA, Public Library. He also executed themes of a regional nature, as in Massilia, Greek Colony and Marseille, Gateway to the Orient (1867–9) for the ceremonial staircase of the Palais Longchamp in Marseille and in Pro Patria Ludus (1880–82) for the staircase of the Musée de Picardie at Amiens. Among his most renowned and important decorative schemes were, in 1893–8, again for the Panthéon, the decoration of four inter-columnar areas with St Geneviève Keeping Watch over Sleeping Paris and the Provisioning of Paris, as well as a frieze of saints, for which he executed only cartoons and which were completed in 1922 by his pupil Victor Koos (b 1864); in 1889–91, for the great amphitheatre at the Sorbonne in Paris, a vast scheme evoking the various disciplines taught there; and in 1891–2, for the Salon du Zodiac of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, Summer, Winter and four corner pieces, and in 1894, for the Prefect’s Staircase, the ceiling painting Victor Hugo Offering his Poetic Talent to the City of Paris. The only works in which Puvis evoked contemporary fashion are Inter Artes et Naturum, Ceramics and Pottery (1888–91) for the staircase of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen. Within the limits of a given iconographic programme, Puvis strove to remain master, and he never repeated himself exactly, although certain figures do reappear in several different works. Puvis always made reference to a humanism and system of philosophy of a very traditional nature, which was outmoded for his time. He sought to express simple ideas in an immediately readable form.

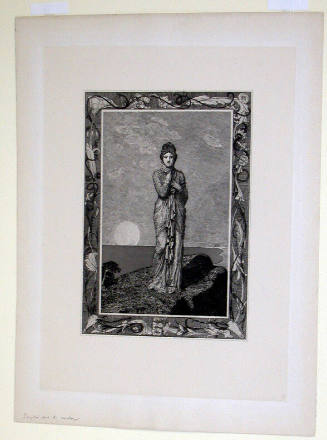

Even though Puvis declared the ‘true role of painting is to animate walls. Apart from that, one should never create paintings larger than one’s hand’ (quoted in Vachon, p. 33), his catalogue is not limited to decorative works. Adapting his principles of decoration, he produced a number of easel paintings, most of which were sold through the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Among these are works on religious subjects, such as the Beheading of St John the Baptist (1869; U. Birmingham, Barber Inst.), the Magdalene in the Desert (c. 1869–70; Frankfurt am Main, Städel. Kstinst.) and the Prodigal Son (1879; Zurich, Stift. Samml. Bührle). Other works are associated with the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71: The Balloon (1870), the Carrier Pigeon (1871; both Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) and the two versions of Hope (1872; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay; Baltimore, MD, Walters A.G.). Such works as Orpheus (1883; priv. col., see exh. cat., p. 184) and The Dream (1883; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) are Symbolist in subject. In addition to these commissions, Puvis used the same methods to produce decorative panels, for example Sleep (1867; Lille, Mus. B.-A.), Summer (1873) and Young Girls by the Sea (1879; both Paris, Mus. d’Orsay). He also produced some superb portraits: Eugène Benon (1882; priv. col., see exh. cat., p. 179), Princess Marie Cantacuzène (1883; Lyon, Mus. B.-A.) and a Self-portrait (1887; Florence, Uffizi). In The Poor Fisherman (1881; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) Puvis achieved a great force of expression with minimum means, creating a painting that is neither Realist nor Symbolist but independent of every age and every school.

Puvis produced thousands of drawings, most of them preparatory ones. The majority of these are owned by his heirs, and 1000 were left by his heirs in 1899 to the towns that own his decorative works. His caricatures have a certain force and ferocity; also, from the 1880s he executed numerous pastels.

2. Reputation and influence.

Puvis acted frequently as a member of the Salon jury, but disapproving of its intolerance he resigned in 1872 and again in 1881; his painting Death and the Maidens (Williamstown, MA, Clark A. Inst.) was submitted in 1872 and rejected. In 1890, together with Ernest Meissonier and Auguste Rodin, he founded the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and became its Vice-President, then President in 1896 on the death of Meissonier. Puvis received all the official honours that could be granted to a 19th-century French artist, and the banquet held in his honour in 1895, attended by poets, writers, artists and musicians, was a formal confirmation of the status accorded him by his contemporaries.

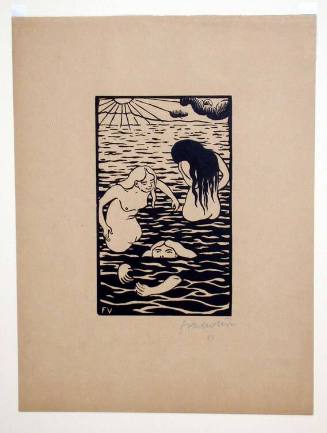

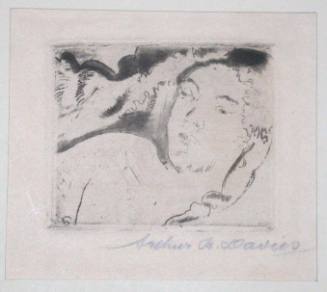

The influence of Puvis was enormous. It extended well beyond the studio that he ran, first with Elie Delaunay and then alone, and to which Victor Koos (b 1864), Paul Baudouin (1850–1928), Ary Renan, Auguste Flameng (1843–93), Henry Daras (1850–1928), Frédéric Montenard (1849–1926), Georges Clémansin du Maine (1853–after 1896), Emile-Alfred Dezaunay (1854–1938) and Adolf Karol Sandoz (1845–after 1925) all belonged. It extended even beyond such direct imitators as Alphonse Osbert and Alexandre Séon. This influence is supported by the writings and works of a wide variety of artists: Edmond Aman-Jean, René Ménard (1862–1930), Henri Martin, as well as Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Odilon Redon, the Nabis with Edouard Vuillard and Maurice Denis and, in the 20th century, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. His influence extended outside France to such artists as Xavier Mellery in Belgium, Vilhelm Hammershøi in Denmark, Ferdinand Hodler in Switzerland, Arthur B. Davies in England and Maurice Prendergast in America. Besides the copying of certain motifs, all these artists were seeking in Puvis a sense of organization of space, a certain type of integration of the human figure and landscape, a sense of gesture and the will to keep the painting on the surface plane.

In 1897 Puvis married Princess Marie Cantacuzène, whom he had met at the home of Chassériau and with whom he had had a relationship since 1856. She died in August 1898, and Puvis, profoundly affected by her death and by two successive accidents of his own, died soon afterwards.

Marie-Christine Boucher. "Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T070147 (accessed March 7, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual