Sheila Metzner

American, born 1939

By Frank Van Riper

Special to Camera Works

Combine a love and a passion for a place with the peculiar properties of Polaroid PolaPan.

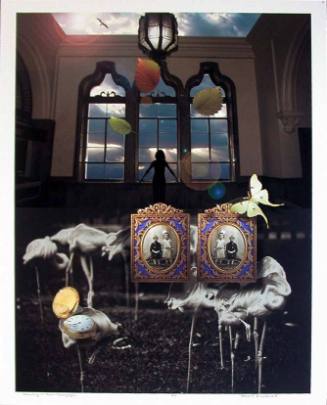

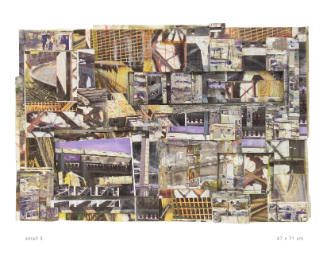

Add to that the depth and patina of a platinum print, and you have – in addition to alliterative overload – the magic that photographer Sheila Metzner has achieved in her glorious new work, New York City 2000.

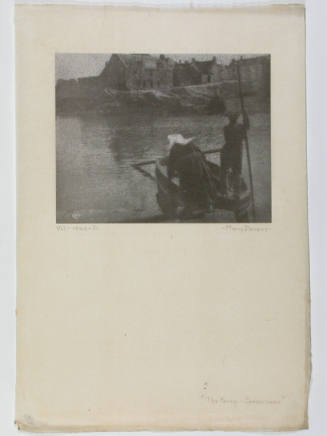

The large 22"x18" platinum prints of New York landmarks that held me in their grip at the elegant John Stevenson Gallery in Manhattan several weeks ago, actually are a collaboration: between photographer Metzner and master platinum printer John Marcy of Florence, Mass. The unlikely juxtaposition of techniques – using Polaroid's 35mm PolaPan instant positive slide film (which Metzner rightly calls as delicate as "butterfly wings") with the long and painstaking process of platinum printing, seems at first bizarre, even unnatural.

But the results are some of the richest, deepest, most compelling platinum images I ever have seen.

Metzner concedes that she had reservations about following in the photographic footsteps of legends like Abbott, Bourke-White and Stieglitz. But during what turned into a frenzied one-month personal project, she found that the buildings and bridges of her city had "a life of their own."

"From the very first bridge," Metzner said in a phone interview from Manhattan, "I was translating it in the camera. What I was going to get was not what I saw."

Which, of course, explains how Metzner was able to make new all over again photography of such oft-shot sites as the Empire State Building, the Brooklyn Bridge and the Chrysler Building, among others.

In one nighttime image the Empire State Building appears bathed in a smoke-like umbra; in another, late afternoon light rakes the building's front, creating brilliant linear highlights.

"This is my New York. It glows," Metzner exulted in the program notes for her opening at the Stevenson Gallery last September. "I own the Brooklyn Bridge and the George Washington Bridge," she declared. Then she added, lest anyone think she were getting too full of herself: "Ask my kids…. They've been told that for years. Of course I pay my toll on the G.W. I don't want to make an issue of my ownership. I prefer to remain invisible."

To call Metzner a woman of many parts is to understate. At 61, she has mastered several careers, not least of which includes raising five children while climbing first the corporate advertising and then the commercial/fine art photography ladder.

In fact, Metzner's biography has a kind of fairy tale quality to it. When one of her early photographs caught the eye of the legendary curator John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art, he included it in the landmark 1978 exhibition, "Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960." But if that weren't enough good luck for a relatively unknown shooter, the New York Times gave her photo full page display in its Sunday Magazine. Later that year, Metzner's first solo show at the Daniel Wolf Gallery drew record crowds – and that show got another huge publicity hit, again in the good grey Times.

From there, her career flourished – aided of course by the fact that she was very, very good: a photographer who could shoot for the long haul, not a trendy one-shot wonder. Her commercial work has included fashion, editorial, advertising, book and CD covers – even special assignment shooting for films. She also has directed television commercials and produced and directed her own short film on the artist Man Ray.

As I said: a woman of many parts.

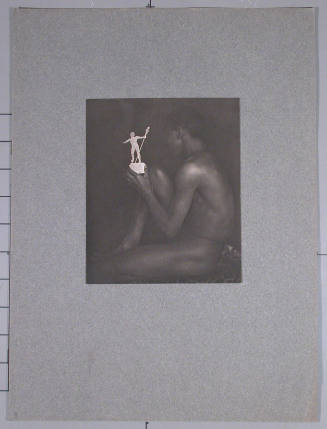

But in the fine art world – and later, to a certain extent, in the advertising world – Metzner is best known for her beautifully composed, painterly color images, including still lifes, nudes and others, produced for her by the Fresson family outside of Paris. The family's prints, which are named after them, are true pigment prints, made in a time-consuming four-color "process de charbon" that gives a pointillist quality to the finished product that wonderfully complements Metzner's vision.

These prints also are said to be the only truly archival color prints in the world.

Which may help explain why, for her bxw New York project, Metzner was drawn to platinum prints, which John Stevenson calls "the most archival of any image[s] made on paper." In addition, platinum prints offer the viewer such a hugely expanded tonal range from black to white, compared to conventional silver prints, that the images literally seem three-dimensional because of their incredible depth and range.

To best achieve this Metzner chose to work in PolaPan – a quirky film at best, whose archival permanence is anyone's guess. It only comes in 35mm. You have to bracket exposures like crazy. And to process it requires a separate apparatus that looks like an old Kodak Day-Load film tank – all clicks and whirls and turnings of gears. But the end product, if all goes right, is a 35mm strip of 36 extremely delicate positive slides that offer up their own peculiarly beautiful tonal range. And so it went for a month.

Once the pictures were made and chosen, it fell to John Marcy to do his own magic. In an interview, Marcy reiterated the costly and time-consuming process. He noted that his rejection rate is roughly one third. [NB: that means one out of three of his prints is bad; most other platinum printers probably would be happy if one out of ten of their prints were good.]

Platinum printing is a contact printing process – i.e., negative in direct contact with sensitized paper, then subjected to ultraviolet light and finally a chemical bath to bring up the image.

But Metzner's original PolaPan images not only were tiny (35mm), they were positives. To create a 22" x18" negative for contact printing, Marcy projected the PolaPan image onto a large sheet of continuous tone film in the darkroom, developed that film conventionally, then used the resulting negative to create a platinum print on 100 percent rag watercolor paper.

Described like this, the process inevitably loses some of its mystery. But as Metzner once said, "Photography [itself] in its most basic form is magic.…This image, caught in my trap, my box of darkness, can live. It is eternal, immortal."

It is … magic.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/photo/galleries/essays/001215.htm

go to http://www.sheilametzner.com/ for bio and other information about artist.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- female