Jean-François Millet

Born Gruchy, nr Gréville, 4 Oct 1814; died Barbizon, 20 Jan 1875.

French painter, draughtsman and etcher. He is famous primarily as a painter of peasants. Although associated with the Barbizon school, he concentrated on figure painting rather than landscape except during his final years. His scenes of rural society, which nostalgically evoke a lost golden age, are classical in composition but are saturated with Realist detail (see Realism). Millet’s art, rooted in the Normandy of his childhood as well as in Barbizon, is also indebted to the Bible and past masters. His fluctuating critical fortunes reflect the shifting social and aesthetic lenses through which his epic representations of peasants have been viewed.

1. Life and work.

Born into a prosperous peasant family from Normandy, Millet received a solid general education and developed what became a lifelong interest in literature. After studying with a local portrait painter, Bon Du Mouchel (1807–46), he continued his professional training in Cherbourg with Lucien-Théophile Langlois (1803–45), a pupil of Antoine-Jean Gros. The talented young artist received a stipend from the city of Cherbourg and went to Paris where he entered the atelier of the history painter Paul Delaroche. Frustrated and unhappy there, Millet competed unsuccessfully for the Prix de Rome in 1839 and left the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. One of the two portraits that he submitted to the Salon of 1840 was accepted. In 1840 Millet moved back to Cherbourg and set himself up as a portrait painter, returning the following year to Paris.

Millet’s early years (c. 1841–8) were dominated by portraiture, which represented the most lucrative (and often the only) means for a 19th-century artist to earn a living, especially in the provinces. Such early portraits as his Self-portrait (c. 1840–41) and the touching effigy of his first wife, Pauline-Virginie Ono (1841; both Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), are characterized by strongly contrasted lighting, dense, smooth brushwork, rigorous simplicity and directness of gaze. The beautiful black conté crayon study of his second wife, Catherine Lemaire (c. 1848–9; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.), with its sensitive crayon strokes and monumentality, heralds a new phase in Millet’s artistic evolution, which coincided with his move to Barbizon in 1849. After 1845 Millet painted few portraits, although he continued to make portrait drawings. During the 1840s Millet struggled to survive financially in Paris, lost his first wife in 1844 and failed to achieve critical recognition. In addition to portraits, he produced pastoral subjects and nudes during the 1840s. Around 1848 Millet became acquainted with several of the Barbizon artists, notably Théodore Rousseau who became a close friend. Through an arrangement with Alfred Sensier (1815–77), Millet was able to guarantee his family’s livelihood.

Millet’s epic naturalist style, which surfaced in the peasant scenes he painted after he settled in Barbizon, coincided with the Revolution of 1848 and his escape from the city. From 1849 Millet specialized in rural genre subjects, which melded together current social preoccupations and artistic traditions. In the aftermath of the Revolution these subjects took on socio-political connotations. Rural depopulation and the move to the cities made the peasant a controversial subject. At the Salon of 1850–51, Millet attracted the attention of both conservative and liberal critics with The Sower (1850; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.). The powerful, striding peasant, exhibited in the same year as Gustave Courbet’s controversial Stonebreakers (destr.) and Burial at Ornans (Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), imbued the common man with a sort of epic grandeur. Millet’s Sower represents the endless cycle of planting and harvesting and physical toil with dignity and compassion. To conservative critics, there was something distinctly disquieting about this hulking, monumental peasant with his forceful gesture and coarse, unidealized features. To progressive critics, however, the art of Millet and Courbet signalled change and the coming of age of the common man as a subject worthy of artistic representation. Yet, ironically, Millet himself was a pessimist who held little hope for reform. In fact, his paintings of peasants often portray archaic farming methods in nostalgic colours and sometimes allude to biblical passages, as in Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz) (1850–53; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.). Millet made numerous preparatory studies for this painting, which he considered his masterpiece and which won him his first official recognition at the Salon of 1853. In this monumental, classicizing harvest scene, Millet paid homage to his heroes, Michelangelo and Nicolas Poussin. The critic Paul de Saint-Victor (1825–81) perceptively described Millet’s Harvesters as ‘a Homeric idyll translated into the local dialect’ (Le Pays, 13 Aug 1853).

Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, oil on canvas, 853×1110 mm, 1857…In 1857 Millet exhibited The Gleaners (Paris, Mus. d’Orsay) at the Salon. This grandiose canvas represents the summation of Millet’s epic naturalism. Three poor peasant women occupy the foreground of the composition, painfully stooping to gather what the harvesters have left behind as they were entitled to by the commune of Chailly. In the background Millet painted with chalky luminosity the flat, fruitful expanse of fields with the harvest taking place. The painting was attacked by conservative critics, such as Saint-Victor, who characterized the gleaners as ‘the Three Fates of pauperdom’ (La Presse, 1857). The three impoverished women, like the figure in The Sower, raised the spectre of social insurrection and belied government claims about the eradication of poverty. However, Millet’s painting was defended by leftist critics for its truth and honesty. The Realist critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary noted the beauty and simplicity of the composition despite the misery of the women and evoked Homer and Virgil. The monumental, sculptural figures, with their repetitive gestures, are in fact reminiscent of the Parthenon frieze, and the painting itself, despite its apparent naturalism, is composed with mathematical precision. The Gleaners, like Millet’s other canvases, both reflects and transfigures the realities of rural life by filtering them through the lenses of memory and past art.

Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, oil on canvas, 555×660 mm, 1857–9…The Angelus (1857–9; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), which was commissioned by Boston artist Thomas Gold Appleton (1812–84), exemplifies Millet’s fluctuating critical reputation. Its widespread vulgarization and unusually specific subject-matter verging on the mawkish have made it Millet’s most popular painting. A young farmer and his wife, silhouetted against the evening sky, pause as the angelus tolls, the woman bowed in prayer, the man awkwardly turning his hat in his hands. In 1889 the painting was the object of a sensational bidding war between the Louvre and an American consortium that bought it for the unprecedented sum of 580,650 francs. Billed as the most famous painting in the world, The Angelus was triumphantly toured around the USA. In 1890 Hippolyte-Alfred Chauchard acquired the painting for 800,000 francs, and it entered the Louvre in 1909. However, by that date Millet had fallen out of fashion and the painting became a subject of derision. The Angelus, with its rigid gender differentiation, later became a veritable obsession for the Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí.

Jean-François Millet: Haystacks: Autumn, oil on canvas, 33 1/2 x…During the 1860s Millet continued to exhibit peasant subjects, most often single figures. Successful and financially secure, he enjoyed a growing reputation, enhanced by the retrospective of his work held at the Exposition Universelle of 1867 in Paris. In 1868 he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. From 1865 Millet turned frequently to pastels and devoted himself increasingly to landscape painting although he never abandoned the human figure (see fig.). In particular, he completed the monumental series the Four Seasons (1868–74; Paris, Mus. d’Orsay), commissioned by Frédéric Hartmann (d 1881) for 25,000 francs. These landscapes, with their loose, painterly brushwork and glowing colour, form the connecting link between the Barbizon school and Impressionism. In 1870 Millet exhibited at the Salon for the last time. At a public sale held in 1872 his works fetched high prices. In 1874 Millet was commissioned to paint murals illustrating the life of St Geneviève for the Panthéon, Paris, which he was unable to carry out. One of his last completed works is the horrifying but hauntingly beautiful Bird Hunters (1874; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.), which represents an apocalyptic nocturnal vision recollected from his childhood—an elemental drama of light and dark, of life and death. Severely ill, Millet married his second wife, Catherine, in a religious ceremony on 3 January 1875 and died on 20 January. He was buried at Barbizon next to Rousseau.

2. Working methods and technique.

Millet was an exceptional draughtsman whose drawings have perhaps withstood the test of time better than his paintings. His varied graphic oeuvre ranges from rapid preparatory studies (most often in black crayon) to carefully finished pastels, which he sold to collectors for high prices during the last decade of his career. Drawings, which enabled Millet to perfect his compositions, were the building blocks for his paintings. Millet worked in the traditional manner, sometimes producing numerous preparatory studies for a single painting. In particular, he was a master of light and dark, as such nocturnal scenes as Twilight (black conté crayon and pastel on paper, c. 1859–63; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) attest. Millet’s drawings, in their predilection for the expressive effects of black and white, foreshadow those of Georges Seurat and Odilon Redon.

Technically it is Millet’s pastels, many of which were commissioned by the collector Emile Gavet (1830–1904), that are the most innovative. Although he had worked in pastel as early as the mid-1840s, Millet turned to the medium with increasing regularity after 1865 and developed an original technique in which he literally drew in pure colour. Beginning with a light chalk sketch, he applied the darks, then rubbed in the pastels to create the substructure and finally built up the surface with mosaic-like strokes of colour. He soon lightened his technique and experimented with different coloured papers, which he allowed to show through in the finished composition. Millet’s pastels, in their marriage of line and colour, point forward to Impressionism and Edgar Degas. With typical modesty, Millet referred to his pastels simply as dessins.

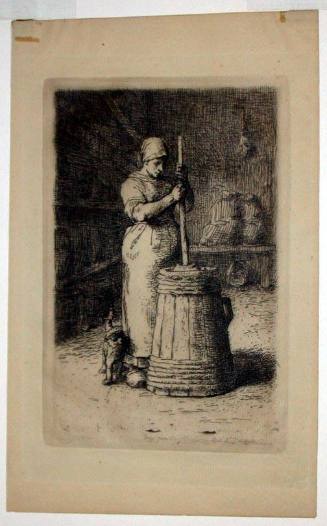

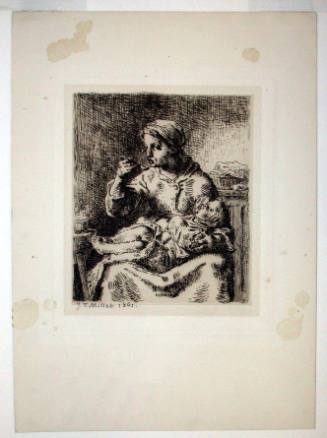

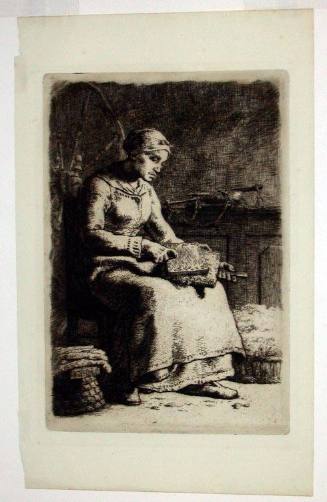

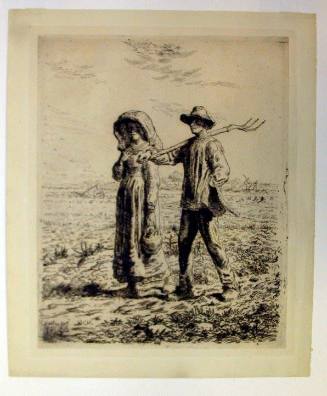

Although printmaking was never a central activity for Millet, he created in the 1850s and 1860s a series of etchings that often reproduced motifs from his paintings. Millet, like other artists of his generation, was part of the general revival of printmaking in the mid-19th century. He probably began etching about 1855, although Melot (1978) has suggested that he may have begun earlier. Alfred Sensier urged Millet to create a series of etchings from his own designs for commercial publication in the hopes of expanding the market for his art. Millet’s etchings, such as Woman Churning Butter (1855–6; Delteil, no. 10), illustrate his technical skill with the etching needle although they are generally less forceful than his preparatory drawings. In some instances, however, Millet’s etchings anticipate his paintings as in the case of The Gleaners. Woman Carding Wool (1855–6; d 15) is one of the most monumental images that Millet created in the etching medium.

Jean-François Millet: Autumn Landscape with a Flock of Turkeys, oil…Millet’s work illustrates the complexity of the Realist enterprise at mid-century. His art is a dialogue between past and present—radical in its humanitarian social creed but traditional in technique and classicizing in composition. Millet’s rural subjects are drawn from contemporary social reality but interpreted in a highly personal manner. His art influenced Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, notably Camille Pissarro and Vincent van Gogh, who idolized Millet and copied a number of his compositions. Even if the peasant no longer strikes the same sympathetic chords for the 20th-century viewer, one cannot help but be moved by the humble majesty of Millet’s ageless figures who fill the gap between earth and sky (see fig.). The retrospective exhibitions held in Paris and London (1975–6) and Boston, MA (1984), provided comprehensive overviews of Millet’s varied oeuvre.

Heather McPherson. "Millet, Jean-François." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T058295 (accessed March 7, 2012).