Albrecht Dürer

German painter, draughtsman, printmaker in both relief and intaglio, and theoretician; the first artist in northern Europe who transformed the arts from the product of the essentially medieval workshop to a conscious expression of artistic genius. He sought to learn the general laws underlying Italian Renaissance art—the laws of optics and the ‘rules’ of ideal beauty and harmony—and he succeeded in synthesizing these laws (Kunst in Dürer's terminology) with his own northern heritage with its interest in the particular and emphasis on practical skill (Brauch). Through his woodcuts and engravings (see line engraving), most of them published by himself, he became an international figure, supplying iconographic models to artists throughout Europe and setting new standards of technical mastery.

Dürer was born in Nuremberg, second son of Albrecht Dürer the elder, a goldsmith from Hungary, who had trained in the Netherlands, and godson of Anton Koberger, one of Germany's foremost printers and publishers. Until the age of 5 he lived in a house behind that of the rich patrician and humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, and at 15 he was apprenticed to the leading painter and book illustrator in Nuremberg, Michael Wolgemut. These four men exercised a powerful influence on Dürer and determined to some degree his artistic career. The father must have taught him the rudiments of drawing, particularly with silverpoint, as is borne out by the 13-year-old boy's self-portrait (1484; Vienna, Albertina). From Wolgemut Dürer learned the painter's trade and the technique of woodcut. Through Koberger he had access to the world of books and learning, and Pirckheimer directed these interests towards Italy and the new humanism.

After completing his apprenticeship Dürer set out in 1490 on the customary journeyman years. He was supposed to go to Colmar to work under Martin Schongauer; when he arrived early in 1492, Schongauer had been dead for nearly a year and his three brothers recommended that he go to Basle, one of the great centres of European book production. The designs in many of the illustrated books published there 1492–4 have been attributed to Dürer, including those in the 1494 edition of Sebastian Brant's Narrenschiff. The one certain attribution to Dürer is the frontispiece for the Letters of S. Jerome, published in 1492. By 1494 Dürer was in Strasbourg, another publishing centre, before returning to Nuremberg the same year. It was probably in Strasbourg that he produced the first and most charming of his painted self-portraits (1493; Paris, Louvre).

Back in Nuremberg a marriage had been arranged for Dürer by his father. A drawing of Agnes Frey, Dürer's wife, inscribed ‘mein angnes’ suggests affection (Vienna, Albertina), though indications are that the marriage, which remained childless, was unhappy. Dürer left his wife almost immediately on his first trip to Venice (summer 1494–spring 1495), one of the earliest northern European artists to experience the Italian Renaissance on its native soil. The main evidence for the trip consists of drawings and watercolours of Alpine views and Venetian costume studies.

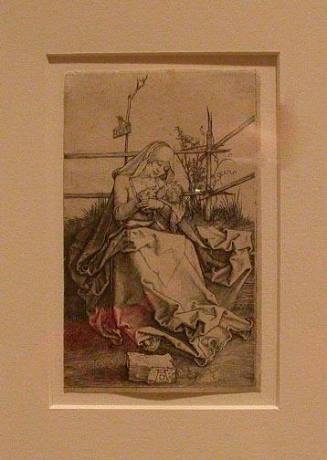

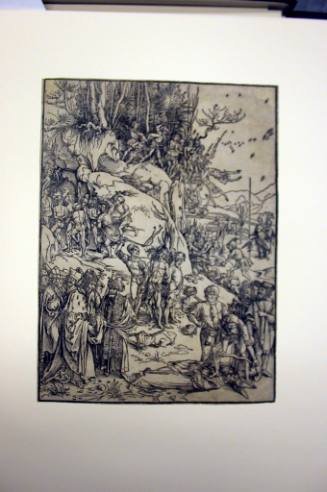

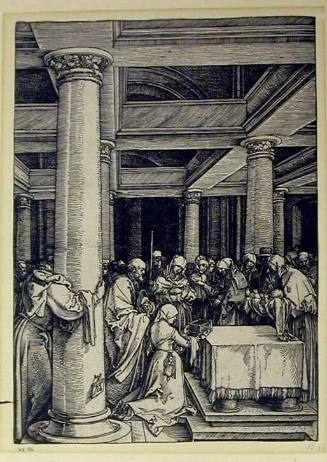

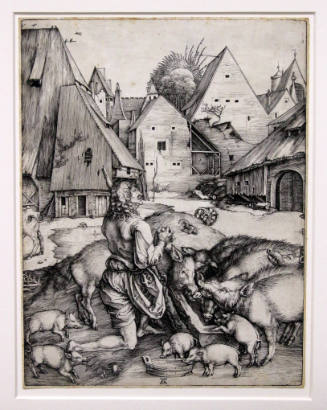

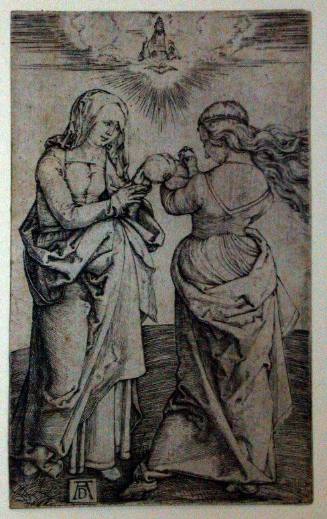

After his return from Italy Dürer settled down in Nuremberg. There followed a decade of extraordinary productivity, during which he carried out numerous paintings—the Self-Portrait of 1500 (Munich, Alte Pin.) and the Adoration of the Magi (1504); (Florence, Uffizi), originally commissioned for the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg, being the most important early works. He began to print and publish his own woodcuts and engravings, including the Apocalypse (1498), the Large Woodcut Passion (1510), and the Life of the Virgin (1510), and continued to draw and paint in watercolours for his own pleasure and instruction (e.g. the Hare, the Blue Roller, and the Great Piece of Turf, all Vienna, Albertina). At the same time he occupied himself with the Renaissance problems of perspective, of absolute beauty, of proportion and harmony. He sought instruction from Jacopo de'Barbari, an Italian artist who was visiting Nuremberg at the time, and he read Vitruvius. The engravings of Adam and Eve and the Nativity, both of 1504, are the first fruits of these investigations.

Dürer's prints of these years established his international reputation so that on his second trip to Italy, 1505–7, he was no longer an unknown young northerner but the most celebrated German artist of his age. Upon his arrival in Venice he secured the commission for an altarpiece in the church of the German community, S. Bartolommeo. The theme of the large panel is the Feast of the Rosegarlands (now Prague, Národní Gal.), which celebrates the brotherhood of all Christians in their devotion to the rosary. Dürer elaborated the act of distributing the rosary by presenting it as a type of sacra conversazione, an Italian subject that features the Madonna and Child enthroned, flanked by saints and donors arranged in a frieze composition. According to his own testimony, the painting was much admired by fellow artists and the aristocratic community in Venice. In its enriched sense of colour, the S. Bartolommeo altarpiece paid tribute to Venetian art, particularly to Giovanni Bellini, whom Dürer met personally and of whom he wrote that he was ‘very old but still the best painter of them all’ (letter to Pirckheimer, 7 Feb. 1506).

Dürer relished the social position accorded to artists in Italy when he stated in a letter (dated 13? Oct. 1506) to Pirckheimer: ‘How shall I long for the sun in the cold; here I am a gentleman, at home I am a parasite.’ Back in Nuremberg, he tried to attain a similarly elevated position. He bought a large house, wrote verse, studied languages and mathematics, and began to draft an elaborate treatise on the theory of art. He succeeded in bringing out three books on geometry, on fortifications, and on the theory of human proportions, this last appearing posthumously. At the same time, he received commissions for altarpieces, not only from his home town (Adoration of the Trinity, 1511; Vienna, Kunsthist. Mus.), but from as far afield as Frankfurt, where Jakob Heller commissioned the Assumption of the Virgin for the Dominican church there (1509). The central panel by Dürer was destroyed in 1729 (copy by Jobst Harrich; Frankfurt, Historisches Mus.) but over 20 preparatory sketches for the composition survive, among them the famous Praying Hands (Vienna, Albertina).

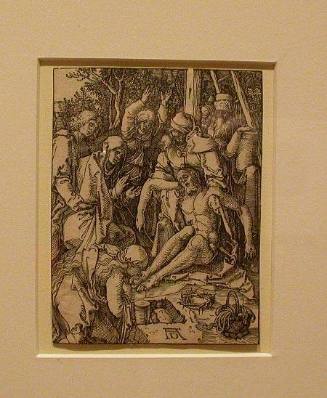

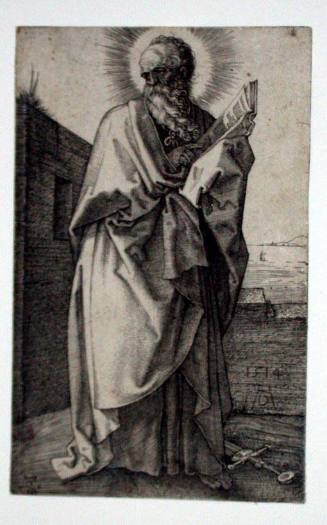

From about 1511 Dürer also turned with increased energy to his graphic works, experimenting with tonal effects more than he had before the Venetian journey. He produced three ‘master engravings’ in 1513 and 1514 which are exceptionally large in size, meticulous in technique, and unprecedented in the representation, by linear means alone, of texture, lustre, and light: Knight, Death, and the Devil, S. Jerome in his Study, and Melancolia I. At this time he also designed two more Passion series: the Small Woodcut Passion (1511) and the Engraved Passion (1513).

After 1512 Dürer's most important patron was the Emperor Maximilian I. For him he designed an enormous Triumphal Arch and Procession, all on paper and executed in woodcut by members of Dürer's workshop and others. These curious substitutes for true Renaissance pageantry may seem to us rather more intriguing than satisfactory. Dürer is more himself in the marginal drawings for the Emperor's Prayer Book (to which Lucas Cranach the elder, Altdorfer, and Burgkmair also contributed). Works of this kind, which mark the so-called ‘decorative’ phase of the master's œuvre (he also designed armour and silverware), end with the death of Maximilian in 1519 and his own conversion to Lutheranism c. 1520.

Dürer's religious beliefs did not however prevent him from travelling to Aachen to attend the coronation of Maximilian's successor, the ultra-Catholic Emperor Charles V, and to secure the renewal of his pension granted him by Maximilian. This was the occasion of Dürer's year-long trip to the Netherlands (1520–1), this time accompanied by his wife. The journey, his last, was as much the artist's triumphal tour as a sightseeing and sketching expedition (Silverpoint Sketchbook, dispersed among several museums) and a sales and shopping trip (Agnes Dürer was in charge of selling her husband's prints at fairs). In Ghent, his enthusiasm for the great altarpiece by Hubert and Jan van Eyck was matched by his interest in the lions kept at the zoo, which he drew in his sketchbook (Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett). He also was attracted by the unusual objects sent to Charles V from Mexico, gifts given to Cortés by the Mexican Emperor Montezuma, which were on display in Brussels while Dürer was there: ‘All the days of my life I have seen nothing that rejoiced my heart so much as these things, for I saw amongst them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle Ingenia of men in foreign lands. Indeed I cannot express all that I thought there’ (Netherlandish Diary, 26 Aug.–3 Sept. 1520).

After his return from the Netherlands, already weakened by a malarial fever contracted there, Dürer was busy with painting portraits and with small-scale engravings, many of them portraits in profile. His last important paintings were the monumental panels with the Four Apostles. They were donated by the artist to the city of Nuremberg (now Munich, Alte Pin.), which eighteen months earlier had adopted Lutheranism as its official religion. Referred to in Dürer's letter of dedication ‘a remembrance in respect for your wisdom’, they are inscribed with texts which are meant to castigate both papists and the more radical Protestants falsifying—in Dürer's view—Luther's teachings (such radical views were expressed by the Beham brothers and Georg Pencz).

When Dürer died in 1528, though he was widely known as a painter, his real fame rested on his graphic work which was used in the north and the south. He who may be said to have brought the Italian Renaissance to northern Europe, in turn influenced Italy through his prints. He supplied artists with motifs very much as pattern books had. His originality of invention—encouraged by the medium which required no commission—led to new and unusual iconographic forms, especially in secular subjects. Beyond that, he had elevated the print to a great expressive medium, unsurpassed until Rembrandt.

Belkin, Kristin. "Dürer, Albrecht." In The Oxford Companion to Western Art, edited by Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/opr/t118/e790 (accessed April 27, 2012).