Lucas Cranach

Nothing is known of the start of Cranach's career or who his master was. The earliest of his extant paintings date from between 1502 and 1505, by which time he was already 30 years old, and they differ markedly from the rest of his work. Their style suggests that the young Cranach had been heavily influenced by Jan Pollak (or Pollonus) of Cracow, who settled in Munich about 1480. It also seems likely that Cranach went to Vienna about 1502, because his St Jerome dated 1502, found in Linz (in the Vienna Museum), the Crucifixion from the Scottish convent in Vienna, thought to be his first painting, the Munich Crucifixion dated 1502, and the Berlin Rest on the Flight into Egypt of 1504 form a stylistically homogeneous group that relates to the Danube style then flourishing in southern Germany, the best-known representatives of which are Altdorfer and Wolf Huber. Cranach's early paintings have an exquisite charm. The scenes from religious history are located in landscapes that are Germanically romantic, with rocks and pine or oak forests stylised in the flexible, elaborate and artificial manner of the Danube School. Everything is governed by the same expressive intention, and the unreal limpidity of the colour, the movements of the figures, and the configuration of rocks and vegetation form a whole that is perfectly coherent, though fairytale-like.

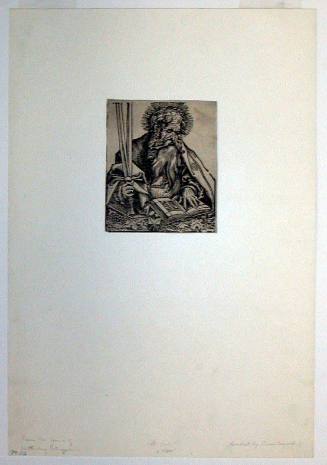

In 1505 Cranach, who must have been known by then, was called to Wittenberg to become court painter to Prince Frederick the Wise. From this moment his art becomes more conventional. The large retable of the Martyrdom of St Catherine (Dresden), painted in 1506, already falls into the contemporary routine of German workshop painting. The figures are schematic and poorly constructed, the faces are inexpressive, and the landscape, which retains some of its romantic characteristics, is now no more than background painting. The series of engravings that Cranach issued between 1506 and 1509 is of very high artistic quality, but also shows the change in his style. The Wittenberg ethos was not as favourable to his development as that of Bavaria. Frederick the Wise, a dedicated collector of paintings and saints' relics, was working hard to create a new artistic centre in a region that had no artistic traditions. Once settled in Wittenberg, Cranach was separated from the main artistic currents of his time. However, we can see the influence on him of Jacopo de Barbari, a Germanising Venetian who visited Wittenberg in 1505. A drawing by Cranach of Diana Sleeping is the result of acquaintance with the anaemic elegance of this painter's figures.

In 1508 Cranach visited the Netherlands, probably on a diplomatic mission, and he painted a portrait of the future Charles V, then aged eight. This contact with the Netherlands is reflected in the Retable of the Holy Family of 1508 (Frankfurt), the clearer and roomier composition of which is clearly inspired by Quentin Masys and de Gossart, and in which we find some Italian influences, particularly Da Vinci and the Venetians. The Madonna and Child in Wroclaw cathedral and the Virgin and Two Saints in Wörlitz also belong to this period. In 1547 John Frederick, Cranach's protector, was taken prisoner at the Battle of Muhlberg and sent to Augsburg by Charles V. From 1550 Cranach shared his patron's captivity. Following his release, he met Titian and painted a portrait of him, but unfortunately this has not come down to us.

After a stay in Innsbruck, Cranach settled in Weimar in 1553. In the city church of Weimar there is an altar with an Allegory of Salvation, a crucifix at the foot of which stand Cranach and Martin Luther. The blood of Christ drips on to the head of the painter. This picture was finished by Lucas Cranach the Younger. During his long life Cranach was court painter to three successive princes of Saxony (Frederick the Wise, died in 1525, his brother John Constant, died in 1532, and John Frederick, died in 1556). The Wittenberg accounts mention portraits of the princes and their wives, religious and mythological paintings, decorative paintings on canvas (Tüchlein), which were replacing tapestries, decorations for fêtes and tournaments, and even the painting of buildings. From this it is clear that the Cranach workshop must have consisted, in addition to his sons, Hans and Lucas, of many assistants and pupils.

Over and above this work, Cranach, a prosperous and influential citizen, was a member of the city council and even Burgomaster of Wittenberg from 1537 to 1544. In 1520 he bought a pharmacy, and later a bookshop to which was attached a publishing house and printing works. He was a close friend of Martin Luther; the two men were godfathers to each other's children and many of Cranach's portraits of Luther survive. He also rendered Luther notable services during the persecution. The spread of Reformation and later Counter-Reformation ideas owed much to the printing press. Cranach engraved portraits and illustrations for the reformer's propaganda pamphlets. Indeed, he made woodcut prints for the first known Reformation broadsheet the Fuhrwagen (the Chariot to Heaven and the Chariot to Hell), illustrating the notion that redemption is a gift of God's grace and not achieved by human will. These varied activities make it a question how much time he spent in his workshop. Cranach signed with his name or initials (generally accompanied by a winged dragon, a blazon granted him in 1508) all works issued from his workshop, and modern critics have difficulty in deciding exactly what is his own work and what that of his sons and assistants. It is agreed that repetitions and variants of quality shall be considered as being by him, but the idea of quality here is not without its ambiguity. The series output of the workshop (an archive note of 1533 mentions an order for 60 painted portraits of the two dead electors), although signed by Cranach, is often not much more than popular imagery. These innumerable repetitions, which flooded the German châteaux and galleries, were made from a single original drawing by the master, usually depicting the head only. Some of these fine sketches have survived (one in the Louvre, thirteen in Rheims museum) and are the only certain evidence we have of Cranach as a portrait artist. In the large paintings produced by the workshop the costumes and armour take up so much space that they overshadow the facial features ( Portraits of Henry the Pious and his wife, in Dresden). Cranach's mature style is in one respect curious. At a time when German painting, as represented by Dürer and Holbein, was moving towards the measured and clear art of the Renaissance, in Cranach we find a return to the Gothic spirit. As with Altdorfer, scenes that contain many figures are an inextricable tangle, suggestive but irrational evocations of the human throng (paintings of the Census of Bethlehem, Dresden, and woodcuts depicting tournaments). However, this archaism gives a very special attraction to his Madonnas, among the finest of which are the Karlsruhe Virgin and the St Petersburg Virgin in a Bower. They depict elegant young women with light hair and clear skin, dressed in the stiff Wittenberg style, and placed in beautiful landscapes. Other paintings, mostly small but numerous, with nude figures standing against a landscape or black background, make up a considerable part of his production. Their sensual charm has attracted people to them throughout the centuries. It is possible that when he was in the Netherlands Cranach was impressed by some the works of Bosch in which we find similar small figures. The account books of the Saxony court contain many references to paintings of this type ordered from Cranach and which were apparently much enjoyed.

In his study of the German School in the Louvre, Louis Réau, insisting on the incompatibility between the bourgeois art of Reformation Germany and the paganism of the Italian Renaissance, writes, in connection with Lucas Cranach's Venus in a Landscape: 'The misunderstanding of antique mythology is grotesque and the ignorance of human form is naive. Because the strict behaviour of the German bourgeoisie forbade painters from using naked models in the studio, they could only reproduce clichés taken from Italian engravings and grossly deformed. Venuses from the Cranach workshop are highly characterised and immediately recognisable: domed foreheads, slanting eyes, frizzy blond hair, small breasts, standing slightly on one leg in a way that is reminiscent of 16th century ivories, with inordinately long, slender legs leading to large, goose-foot feet. Their only clothing is a transparent veil, a gold necklace and sometimes, as a joke, a cardinal's hat. These naked dolls are so lifeless and of such unsightly clumsiness that one is astonished that the humanists of Wittenberg found them attractive. In the work of Lucas Cranach and his son they alternate with Protestant imagery, more edifying, certainly, but even cruder, that found its market in the followers of Martin Luther.' In connection with Portrait of a Young Woman, Réau continues: 'This portrait of a young blonde girl standing against an opaque black background is certainly the work of Lucas Cranach, because it not only carries the mark of the dragon with the wings of a bat, but it has a striking resemblance to other works unquestionably by the Wittenberg master in the museums of Budapest and Weimar.' As to the comments on femininity in Cranach from an otherwise admirable historian, the objective description is quite well observed, but the aesthetic assessment is so extreme as to be worthless.

Cranach's ideal of beauty is exceptional for the 16th-century: he likes the slender sihouettes of hardly nubile girls, with protruding stomachs and slim waists. The flesh tones are delicately anaemic. The undulating line of the body is Gothic. The sensual character of these figures is emphasised by jewellery, hats and transparent veils. Some of them have a passing similarity to Italian art: the large Venus Standing of 1509 (Hermitage), Nymph of the Spring of 1518 (Leipzig) are clearly influenced by the Reclining Venus of Giorgione, the panels of Adam and Eve (Brunswick) are transposed from Dürer. But these are exceptions. Most of the paintings of this kind, whether religious or mythological - Judgement of Paris, Original Sin, Lucretia, Judith Judith, Venus or Bathsheba- are excuses for depicting female nudes of a very Germanic form such as is found, modestly represented, in Dürer, whereas in Cranach it is a seductive combination of naivety and sensuality.

"CRANACH, Lucas, the Elder." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00044115 (accessed April 27, 2012).