Giovanni Battista Gaulli, called "Il Baciccio"

Born Genoa, 1639; died Rome, shortly after 26 March 1709.

Italian painter. He was a celebrated artist of the Roman High Baroque, whose illusionist ceiling fresco, the Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1678–9; Rome, Il Gesù) is one of the most radiant and joyous visions of a triumphant Catholicism. His work, which included frescoes, altarpieces, mythological scenes and portraits, is distinguished by the warm, glowing colour that reveals his Genoese origins.

1. Life and work.

(i) The early years, before 1672.

(a) Altarpieces and frescoes.

No works can be securely attributed to Gaulli’s youth in Genoa; he left the city before 1658 and based himself in Rome for the rest of his life. Working in Rome for the Genoese art dealer Pellegrino Peri, he met Gianlorenzo Bernini, whose support guaranteed his early success. Gaulli was accepted as a member of the Accademia di S Luca in 1662. His first public commission, the altarpiece St Roch and St Anthony Abbot Imploring the Intervention of the Virgin and Child on behalf of the Plague-stricken for the church of S Rocco, shows the profound impression left on Gaulli by the art of his native city. The work in Genoa of Rubens and van Dyck had led painters there, such as Bernardo Strozzi, to work in a broad painterly manner, using dark backgrounds broken by flashes of hot, highly saturated colour. Likewise in S Rocco, Gaulli builds up warm dark colours towards saturation, in glazes over a reddish ground; in the cherub on the left, for example, the whole face is ruddy but where the shadow falls across it, the glow of almost pure red is startling in its intensity. There is also the lingering influence of Genoese Mannerism in the crowded, markedly vertical composition and the elongated figure of St Roch.

Yet in the 1660s Gaulli also experimented with Bolognese classicism. His Pietà (1667; Rome, Pal. Barberini) is an early attempt to master this style; the composition is freely reinterpreted from Annibale Carracci’s Pietà (Naples, Capodimonte). Here he abandoned the loose painterly manner of the S Rocco altarpiece for a hard, predominantly linear type of modelling, with closed brushwork and an emphasis on detail. In place of the dark warm colours of his earlier canvas, shot through with hues of high intensity, he substituted a cool dry palette, moving everywhere towards grey. In contrast to the rather flaccid treatment of the figures in the S Rocco altarpiece and the somewhat mannered treatment of space, the anatomy of the figures is flawless, the draughtsmanship unfaltering and the treatment of space entirely convincing.

Gaulli’s first mature masterpiece is the group of four large pendentive frescoes in the church of S Agnese: Temperance, Prudence, Faith and Charity and Justice, Peace and Truth. He received the commission in December 1666 thanks to Bernini, who recommended him to the Pamphili family, patrons of the church, and completed it in 1672. As part of his preparations (see also §2 below) he travelled in 1669 to Parma to study Correggio’s frescoes in the cathedral. His own work drew together all his previous artistic experience. In their pale hues, their essentially linear techniques and their attention to the clarity of detail, they are indebted to Bolognese classicism. Yet these elements, now fully absorbed, have been drawn into the mainstream of the High Baroque, which Gaulli first encountered in Genoa but developed much further in Rome under the guidance of Bernini and the example of Pietro da Cortona. In each fresco the composition is full and abundant, not limited (as the classicists would have preferred) to the figures that would suffice to explain the theme. Instead they are enriched with many gently moving figures in elaborately convoluted, billowing garments and enlivened by putti and angels in full flight. The altarpieces that Gaulli also painted around this time—St John the Baptist (c. 1670–71; Rome, S Nicolo da Tolentino) and St Louis Beltrán (c. 1671; Rome, S Maria sopra Minerva)—continue however in the Genoese manner of the S Rocco altarpiece.

(b) Portraits.

In his own day Gaulli was admired as a portrait painter, although today we can identify few of his works in this genre. He may have seen portraits by van Dyck in Genoa; his own sometimes suggest the influence of van Dyck’s elegance and painterly refinement. Pascoli tells us that he made innumerable portraits ‘of all the cardinals, of all the great personages in the Rome of his day, and of the seven popes who reigned from Alexander VII to Clement XI’. His earliest known portrait is that of Cardinal Paluzzi degli Altieri (c. 1666; Karlsruhe, Staatl. Ksthalle). There followed the half-length portrait of Alexander VII (1666–7; Munich, Messinger priv. col., see Enggass, 1964, fig.), a more adventurous work. The Pope raises his right hand, and this emphasis on a momentary gesture was admired by Gaulli’s contemporaries: the artist himself said that he had been inspired by Bernini, who believed that the sitter revealed himself more truly in movement and in conversation than when motionless and hushed (Pascoli). Probably a little later, he painted a glamorous, intensely romantic Self-portrait (1667–8; Florence, Uffizi), for which he posed richly clad in golden jacket and velvet cap. The portrait of Pope Clement IX (1667–9; Rome, Pal. Barberini) perfects the theme of the earlier papal likeness. The Pope, right hand raised, is brought closer to the spectator, on whom he turns an intense gaze.

(ii) The middle years, 1672–85.

(a) Il Gesù, 1672–83.

On 21 August 1672 Gian Paolo Oliva, the Father-General of the Jesuit Order, signed a contract with Gaulli commissioning him to fresco the dome, the pendentives and the nave and transept vaults of the church of Il Gesù, Rome. This enormously important commission was won in competition with Giacinto Brandi, Ciro Ferri and Carlo Maratti, and with the support of Bernini, to whom Oliva turned for advice. The nine large frescoes (1672–83) constitute the greatest achievement of the artist’s career and his chief claim to fame. The cloud-borne Vision of Heaven (1672–5) in the huge dome is badly damaged, but the frescoes on the pendentives (1675–6) have survived in almost perfect condition. Two of these four, the Four Evangelists and the Four Doctors of the Latin Church, represent the New Law; the other two, the Leaders of Israel and the Prophets of Israel, the Old. Just as the pendentives form the physical transition that carries the weight and thrust of the dome to the ground below, so the paintings on the pendentives form the metaphysical transition between the vision of heaven in the dome and the congregation on the floor of the church.

The break between these frescoes and the earlier ones at S Agnese is decisive. Except for the smooth surfaces and hard outlines, no trace of Bolognese classicism remains. Deeply saturated hues replace the pale tonalities of the earlier pendentives, powerful rhythms are substituted for gentle movements and the heavy, sharply convoluted, angular garment folds produce highly agitated rhythms, similar to those used by Bernini in his last, most expressionistic phase. In the Leaders of Israel (Moses, Abraham, Joshua and Aaron) Gaulli brings together four twisting, tilted, muscular, interlocked figures, the torsos taken from Michelangelo, the garments from Bernini. Churning rhythms surge through the whole composition which, unable to be contained, breaks sharply out and over the gilded frame, casting a painted shadow on the surface of the dome’s drum.

The style so successfully developed for the pendentives was transferred to the vault of the great nave and reinterpreted, with still more dramatic compositional devices and on a very much larger scale, in the fresco representing the Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1678–9). In this we see the hosts of heaven kneeling in adoration before the divine light that radiates from the monogram of Jesus, drawing the blessed up to heaven and casting the damned down into hell. The fresco falls into three principal divisions: a hollow disc with the monogram in the centre; an arc of clouds supporting a throng of the blessed that spreads out beyond the frame; and a dark triangular mass containing the fall of the damned. The central zone is populated by an immense group of cherubs rising cylindrically around the mystical light source. Almost all are sharply foreshortened. We see them dangling overhead, shooting upward or plunging down below. In the sections closest to the earth these figures retain their solid forms and pink flesh tints. Above them lies a more numerous host of tiny heads pressing toward the light that dissolves their mass and drains their colour.

Far below we see the second group, the great arc of the blessed, which gives the illusion of being on a level just below the vault of the church and breaks out on either side far over and beyond the frame, covering large sections of the architectural decoration. Borne upward on heavy clouds, these clearly outlined figures still retain the customary attributes of human form: the sense of weight, mass and clearly articulated anatomy—in short all the qualities necessary to give the illusion of their immediate and tangible existence. In contrast to the upper levels, the colours are rich and extraordinarily vital. Granting, as in the theatre, a temporary suspension of disbelief, we gaze upward to witness the miraculous intrusion of a heavenly host within the confines of the earthly church.

A triangle composed of figures of the damned concludes the composition. Hurled over the edge of the frame, they spread out into the upper regions of the church, driven downward in a great torrent by the same light that lifts up the blessed. These figures are the most tangible of all. Their writhing forms, contorted with fear and rage, bulge with muscles whose weight seems to increase the speed of their downward plunge. Some represent specific vices: Simony with a purse and tempietto, Vanity with a peacock, Avarice with a wolf, Heresy with a head swarming with snakes.

The most striking aspect of the Triumph is its composition and the blending of architecture, painting and sculpture. Early sources state, and modern critics generally agree, that Bernini played a major role in its development. Precedents are to be found in the ceiling fresco Angel Concert round the Dove of the Holy Ghost, designed by Bernini and executed by Guido Ubaldo Abbatini on the vault of the Cornaro Chapel (1647–52) in S Maria della Vittoria, Rome, and more importantly in Bernini’s Cathedra Petri (1657–66) in St Peter’s.

(b) Other commissions.

While at work on Il Gesù, Gaulli carried out a number of other commissions, mainly religious works, but also a few mythologies and portraits. His most notable religious work is the Death of St Francis Xavier (1676; Rome, S Andrea al Quirinale). The saint, depicted in a highly realistic manner, lies prostrate at the moment of death, his face drained of colour, his head rolled back, his heavy-lidded eyes opening to the celestial vision. Around him, against a field of golden light, float angels and cherubs modelled in pinks and rose. The earthly and heavenly scenes interpenetrate yet are filled with deliberate contrasts, of cool and warm, motionless and motion-filled, dark and light, all giving formal emphasis to the thematic contrast between death and life after death.

Among Gaulli’s mythological paintings are the Bacchanalia (c. 1675; São Paulo, Klabin priv. col.; see Enggass, 1964, fig.)—which echoes the mood of Poussin’s early mythological paintings and of Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (London, NG), then in Rome in the Villa Aldobrandini—and a pair painted c. 1680–85, the Adonis Bidding Farewell to Venus (Burghley House, Cambs) and the Death of Adonis (Oberlin, OH, Oberlin Coll., Allen Mem. A. Mus.). His portraits include the austere and dignified Gianlorenzo Bernini (c. 1673; Rome, Pal. Barberini) and the superb Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (c. 1672–5; Florence, Uffizi). None of the cardinal’s ugliness is withheld, yet this is a sympathetic portrait of a sensitive, contemplative and deeply cultured man, enriched by the remarkable orchestration of the colour. Hunched slightly forward, he looks out at us with partially unfocused, watery eyes, his mouth parted as if he were about to speak, his long delicate fingers toying with the cardinal’s hat. The flesh tones are beautifully modelled, but what gives the painting its sense of inner life is the cape, the folds of which create angular, insistent rhythms. To suggest the shimmer of watered silk Gaulli extends his palette through the whole gamut of reds from pink to wine-black. Stripes of crimson overlay soft rose. In the highlights the brushstrokes are especially free, producing a marvellous iridescence.

(iii) The final years, 1685–1709.

In the late years, responding to the changing taste of his patrons, Gaulli moved away from the High Baroque and adapted his art to the newly fashionable style, a blend of classicism and Baroque, as practised by Carlo Maratti. His colours became less intense and the rhythms of his compositions lighter. In this period he received fewer large commissions, although he went to Genoa in 1693 to discuss a commission to fresco the Great Hall of the Palazzo Reale, and in 1706–7 was asked to paint three frescoes in the hall of the Minor Consiglio in the Palazzo Reale; neither project was fulfilled.

The large Birth of John the Baptist (1698; Rome, S Maria in Campitelli) is a representative example of Gaulli’s late style, in which some aspects of classicism are accepted while others are rejected. As at Il Gesù, he models his figures with smooth hard surfaces and strong outlines. The colours are now much less saturated but still bright: there is nothing dull or dry about them. Zachariah’s cloak is a pale violet. The woman who holds the infant St John wears a tunic that is exquisitely modulated in tones of pink and rose. This is the palette of the contemporary style, the Barocchetto romano, but there is also a significant survival of the Roman High Baroque. The figures crowd the foreground; they are arranged so as to provide recessions along diagonals; and their poses are filled with movement. Most striking of all, especially at this late date, is the use of garment folds based on the late sculpture of Bernini: deep, heavy, angular convolutions that generate tempestuous rhythms and a sense of highly charged emotions.

In 1707 Gaulli completed his last major project, a vault fresco of Christ in Glory Receiving Franciscan Saints (Rome, SS Apostoli). This makes a striking contrast to the Triumph of the Name of Jesus. Both depict a celestial vision crowded with figures and infused with divine light, and both are set in the same frame, but whereas at Il Gesù the cloud-borne figures sweep out beyond the frame, at SS Apostoli they keep strictly within it, even reinforcing it by turning inward. The field is less crowded, allowing greater clarity for each of the figures; garment folds, while still elaborate, are less expressive. Everywhere the rhythms are weaker, the gestures of the figures more subdued. The rich palette for which the artist won such renown has been drained of intensity: the colours are dull and dry. Yet this is not Gaulli’s natural manner. A recently discovered bozzetto (Genoa, priv. col., see Enggass, 1981, fig.) shows his consummate skill as a colourist even when working with lighter, more delicate tones. His changed style in the fresco was undoubtedly something forced on him to meet the demand of his new patrons for a more classicizing approach.

2. Working methods and technique.

Gaulli’s vast decorative schemes involved long and careful preparation, and before he began work on his frescoes he made many drawings and also a number of rapid oil sketches or bozzetti as well as more finished modelli. The bozzetti show his intimate, instinctive personal style, and a comparison of those for the S Agnese frescoes with the finished work reveals how Gaulli transformed his vivid first impressions into the more monumental style of the Roman High Baroque. In the bozzetto for the fresco of Prudence and Faith and Charity (both Rome, 1666–71; Pal. Barberini) the colouristic intensity of his Genoese background bursts forth in full vigour. With hasty strokes he masses brilliant hues, leaving compositional problems for a later phase of the project. In the bozzetto for Prudence the putto in the centre has a flame-red face and a mouth that is a black hollow, as if he were crying out. The putto below him turns sharply in contrapposto, his head thrust out from the green ground like a carved sphere. Four strokes are enough to block out his leg, plus three touches of red in the shadows, yet these are sufficient to give the whole figure a sense of recoil, like a wound spring released.

When Gaulli translated these early impressions into their final form on the broad surfaces of the pendentives of S Agnese he achieved a brilliant blend of styles that are often thought to be antithetical. Hard, smooth surfaces and closed brushwork are used to construct solid figures that are delineated in considerable detail. The colours are far paler than in the bozzetti but more skilfully modulated and more harmoniously distributed. Cangiantismo makes its first appearance in Gaulli’s work: the figure of Fame in the fresco of Temperance has a mantle that is dark violet in the shadows but turns pale green in the light. Major colour schemes such as this are almost always repeated. Thus the putto in the upper left has a scarf with the same cangianti, violet and green, but now with the intensity lowered.

The Triumph of the Name of Jesus is particularly remarkable for its successful creation of illusion through technique. The greater part of the composition lies inside the frame, a heavy gilt stucco moulding that projects between 100 mm and 120 mm from the surface of the vault proper. The vault is elaborately panelled with deep coffers inset with rosettes. Thick layers of plaster overlay the mouldings and fill up the coffers, providing a smooth surface on which the painting is carried over and beyond the frame. Other gilded areas of the vault are overpainted with a dark glaze to indicate shadows cast over the architecture by masses of figures and cloud banks that block off the central radiation of light. This technique permits the illusion that a heavenly host floats not only high above us in the sky but also close to the ground within the very nave of the church where we stand.

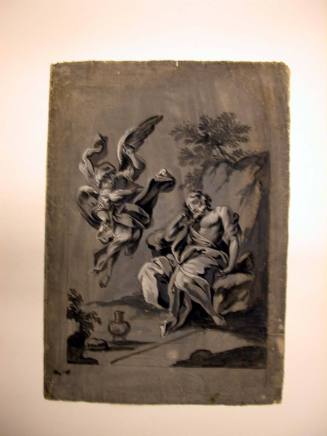

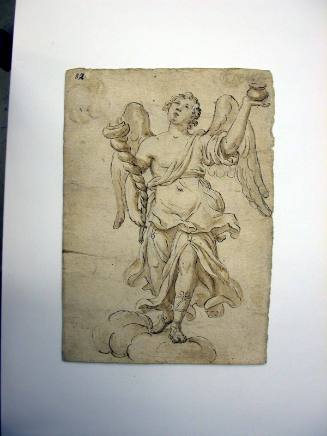

To the corpus of Gaulli’s paintings must be added a very considerable body of surviving drawings. There are more than 300 in the Kunstmuseum in Düsseldorf alone, some two dozen in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and smaller but notable collections in the Cabinet des Estampes at the Louvre, Paris, the Kupferstichkabinett of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, the Print Room of the British Museum in London and in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, Berks. The drawings are done in a wide range of media, on various kinds of paper, in pen and ink with or without washes (which may be in any of a variety of colours), with or without highlights, and in a number of different coloured chalks. All would appear to have been made as studies for paintings, not as ends in themselves. As a group they provide us with invaluable insights into the way in which Gaulli devised the poses of his figures, often making considerable changes, and the manner in which he developed his compositions. A few of his early pen drawings, such as the Esther before Ahasuerus (Oxford, Ashmolean), are done with the greatest rapidity, almost like Rembrandt’s, with large ink blotches providing accents. More often the drawings are careful studies of individual figures, many of which are shown sharply foreshortened and in unusual poses. Their variety is evident in the preparatory drawings for the Adonis Bidding Farewell to Venus, which include a compositional study in pen and ink on white paper, with transparent grey wash (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.), a design in black chalk heightened with white on grey-brown paper, squared in black chalk, and a study for the figure of Adonis, which delicately captures a transient pose, in pen and brown ink over black chalk, with grey wash on grey-brown paper (both Düsseldorf, Kstmus.). A number of portrait drawings survive, among them the Portrait of a Man in black and red chalk (c. 1665; Madrid, Prado), Innocent XI and Clement X (both Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.). In the later part of his life Gaulli became fascinated with garment folds done in the manner that Bernini developed for his late sculpture. Seemingly endless studies, among them the Study for a Figure of the Virgin Mary (Düsseldorf, Kstmus.), are devoted to what are essentially abstract patterns, filled with the ebb and flow of powerful curvilinear rhythms. For the movement of these garments, in most cases, there is no rational explanation. The design itself is its own reason for being.

3. Contemporary and posthumous reputation.

In his own lifetime Gaulli was a highly successful and wealthy artist, the Principe of the Accademia di S Luca in 1673 and 1674 and the owner of a large house on Via del Parione that still stands today. Between 1670 and 1685 he was probably the most highly praised painter in Rome. He never fell completely out of favour during his lifetime, but from about 1685, when his High Baroque style was no longer fashionable, his popularity declined. He altered his style to meet the new trend, and early critics recognized, and regretted, the marked change in his style during his final phase; Pascoli writes:

"Had he but died after he had painted the pendentives of S Agnese … the vault and pendentives … of Il Gesù and the other works that he did in those years and some time after, when, while still in his prime, he worked in a manner that was powerful, extravagant and altogether beautiful, he need not have envied even the greatest masters. But then, abandoning this manner and imitating those who denied themselves deep colours, he changed, and the works that he did thereafter, while still beautiful, lost that which gave them a supreme beauty; and whereas before he was the equal of the most famous, he became afterward less than himself."

Gaulli’s posthumous fame has fluctuated more or less with the acceptance or rejection of the High Baroque. Up until the late 1760s his paintings were generally admired by Italian critics, but as Neo-classicism came increasingly to the fore they fell from favour. References to his work during the 19th century and well into the 20th are always brief and often unfavourable. This began to change, but only gradually, in the years between the two world wars. Even in the mid-20th century the Baroque was often viewed with distaste as being uncouthly demonstrative and patently insincere. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, long seen as the flagship of American museums, was said to be unable to work up an interest in Italian Baroque art because the prices were too low. This situation has changed. American museums now bid eagerly and lavishly for the few authentic works by Gaulli that come on the market. A major monograph on the artist appeared in 1964. Though his most important paintings are in fresco and hence unmoveable, other work of his was exhibited at Oberlin in 1967 and continues to attract the attention of scholars and dealers.

Robert Enggass. "Gaulli, Giovanni Battista." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T031034 (accessed April 10, 2012).