Minor White

American. Born: Minneapolis, Minnesota, 9 July 1908. Education: public schools in Minneapolis, 1913-28; studied botany, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1928-31, 1932-33, B.S. 1933; art history and aesthetics, Columbia University, New York, 1945-46; mainly self-taught in photography, from 1916, influenced by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, New York 1945-46. Military Service: Served as infantryman, United States Army, in the Philippines, 1942-45: Bronze Star. Career: Worked as a waiter and barman, University Club, University of Minnesota, 1933-37; hotel night clerk and assistant in photographic studio, Portland, Oregon, 1937-38; instructor in photography, YMCA, Portland, 1938; secretarial assistant, People's Power League, Portland, 1938; photographer, Works Progress Administration (WPA), Portland, 1938-39; Instructor in Photography, then Director, La Grande Art Center, Oregon, 1940-41; Photographer, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1945; Instructor in Photography, California School of Fine Arts, now San Francisco Art Institute, 1946-52; Founder-Editor with Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, Barbara Morgan, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall and others, and Production Manager, Aperture magazine, San Francisco and New York 1952-75; Exhibitions Organizer, 1953-57, and Editor, Image magazine, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1953-57; Instructor in Photography and Photojournalism, Rochester Institute of Technology, New York, 1955-64; Editor, Sensorium magazine, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965 (not published); Visiting Professor, Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 1965-76. Member, Oregon Camera Club, Portland, 1938; Photo League, New York, 1947; Founder Member, Society for Photographic Education, 1962. Recipient: Guggenheim Fellowship, 1970. Died: (in Boston) 24 June 1976.

A bright, energetic tactician, one versed in the politics of art and the museum and publishing worlds, a teacher with provocative classroom strategies, and a photographer of richly metaphoric images, Minor White was fully conscious of the uniqueness and privacy of his vision and of the roles he maintained as the passing years thinned his hair to diaphanous, white strings: arbiter of photographic tastes, lecturer, director of vigorous workshops, entrepreneur, and editor of quoted and problematical books (Be-Ing Without Clothes and Octave of Prayer).

He brought to his students at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he taught from the mid-60s almost up until his death, a vast experience and knowledge. The standards that he created and upheld for others were standards that he also observed for himself. As with the format and design of Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations, the extensive Aperture monograph of his work published in 1969--the spatter of quotes and poetry, the orchestration of rhythms and enlightening juxtapositions--he was an imaginative and fastidious editor.

For White, a photograph was not simply food for senseless consumption. Its offering of nourishment was more delicate and substantive. Its craft, its shapes, and composition, often predicated by the subject, its unarticulated and subliminal facets of being--some of these, at times most of these, could be deciphered, in fact read, or determined by the exercise of an engaged and watchful intellect. A photograph could also be seen as a metaphorical mirror, reflecting for the viewer as well as for the photographer and critic, feeling-states and resonances that defy facile descriptions.

Through his editorship of Aperture, an influential journal of photography begun in 1952, his curatorial judgements, his own experimentation and creativity, his generous and astute critiques of the work of his colleagues and students, White insisted that if a photograph were worth viewing, it required bold and probing viewing. In White's teaching, scrutiny of a photograph was soulful endeavor; joyful and intense, an often solemn activity that could alter and enlarge one's critical perception, one's creative energies and productivity, and occasionally even one's attitude toward life. Such scrutiny required dedication, integrity, patience, a burgeoning sensibility, and a game covenant with the unknown. As his students were shown, a photograph could be appraised in countless ways--first, for its craft, its elements of composition, its format and print qualities, its freshness of conception; then later for its deeper apprehensions and acknowledgements.

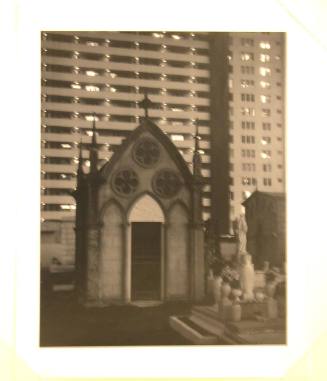

In a public sense, White came to think of photographs principally as either objects to be exhibited in galleries and museums or presented in compelling arrangements in magazines and books. In a private and pedagogic sense, there was an alternative use of photography, that being the opportunity of exploring the interiority of oneself or of studying the exploration and achievement of another human being, at least through the visual manifestation of that exploration and achievement.

During the last phase of his life, this alternative use of photography absorbed more and more of his creative energy and thought. It is what he labored with in his myriad workshops by employing at times provocative silences and cryptically abrasive comments. His students suffered his preoccupations and unsparing aspirations; they were urged to disengage themselves from preconceptions, inhibitions, defense mechanisms, and the telltale smudges of ego. Dance, mime, classical music, readings from esoteric masters, the I Ching--all were used to promote self-discovery and to provide a new context for perception.

``I have been defining creative ever since I came to M.I.T.,'' he observed late in his life, ``as anything which brings us into contact with our Creator, either inwardly or outwardly.'' The source for White's spirituality and some of his workshop techniques came from a Russian, George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1870s-1949). Gurdjieff proposed energizing the three centers of being: intellectual, emotional, and instinctual. After fifty, White adopted Gurdjieff's discipline and philosophy, and they provided lasting sustenance for his intense and hungry spirit.

A poet himself, White thought of poetry as one kind of expression, a harvesting of knowledge within oneself--and of photography as another, as symbolized by one of his supreme images, ``The Sandblaster,'' in which a man is pictured at work, excavating, with only his helmet and shoulders visible. White admitted special fondness for this image; it was a remembrance of himself, digging away at life.

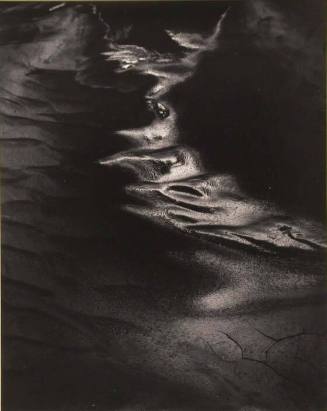

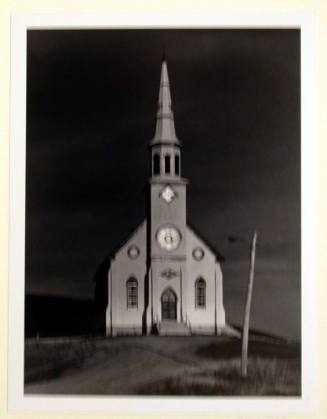

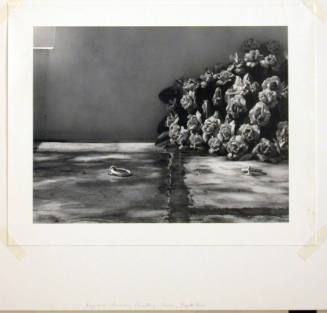

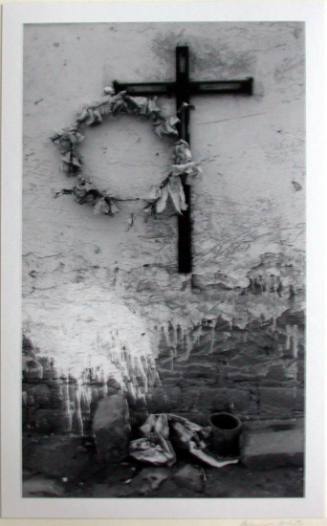

White's early work shot in Portland, Oregon and along the California coast is direct and earthbound--images of rock formations at Point Lobos and of sea flung like wet snow and of streets and buildings that glisten like freshly painted brick and steel. Almost all of his work after 1945, though, yearns in one way or another for the spiritual. The best seem to gain a purchase on mystery and spirit without deserting the mundane. In ``Two Barns and Shadow,'' for instance, the shadow of a telephone pole falls obliquely across a field and points up toward two barns, whose visual arrangement seems something more than ordinary. The image possesses immediate visual coherence, as most of White's images do, and then there is the recognition of another mode. The shadow reads as a black cross and the two barns suggest two sides, one darker and one lighter, of spiritual or psychic being. That image like so many created by White--``Ritual Branch,'' ``Birdlime and Surf,'' ``Long Cloud,'' ``Christmas Ornament,'' and ``Rings and Roses''--abides first in the subtle articulation of light and form.

The non-narrative photographic sequence is White's conceiving. In White's hands a sequence often enacted a dialogue between two people or manifested changing moods and complex feeling-states. For thirty odd years he worked with sequences. Some preserved their original shapes over the years, while others were altered again and again--as often by the inclusion of a new image as by an internal adjustment in sequential order. The individual images were not conceived as from a schedule or filmmaker's script, but first as separate children with equal love and pampering. Scattered about his floor or laid out along the tiers of his wall rack, there were profound differences among them in pitch, density, and velocity. These differences became some of the hidden strings of formal arrangement that ordered images in his sequences.

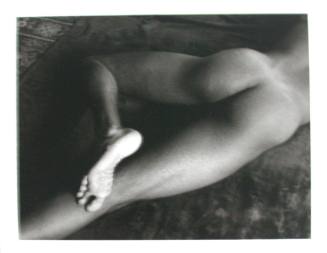

In his mature sequential work, White achieved a context both indecipherable and as tactile as the rock and snow and frosted glass appropriated as canvas. The context was often highly personal--``Sequence 4'' and ``Sequence 17,'' for instance--disclosures of sexuality and states of mind whose lives depend upon revelation but not upon precise identification. ``Sound of One Hand Clapping,'' no doubt his finest sequence, originated from meditations on a Zen koan. Composed of ten images, most of which were frost configurations on the windows of his flat in Rochester, New York, the sequence is a visual equivalent of sound. Covertly hinged together, the images pass from an initial closed and ineffable form to an open showering form. Forces as commanding as hands guide the viewer through the sequence. It is as if the individual images are forms in their secret effulgence, awaiting scrutiny and meditation. Circles, hands, eyes, heads, stars, icicles, scallops of frost, snowbursts--these forms rise and subside, take body and resonance in subtle recurrence. The images seem at first simple and inert, but upon closer scrutiny they break into untutored vitality. They gambol, and chatter, igniting the imagination, exploding into objects of new being.

The bedrock of White's work is self. After 1964, he steadfastly embraced the personal and esoteric. All of his interests and inclinations urged him in that direction: his sexuality; poetry; pedagogy; Stieglitz's equivalence concept, which for him became dogma; oriental ritual, diet, and thought; Gurdjieff work; and the developing concept of non-narrative sequence. Like most of his sequences, ``Sound of One Hand Clapping'' evades literary reduction and interpretation. Through its sound, the liveliness of its forms, the rhythmical and poetic nature of its arrangement, it provokes the viewer in ways that a single image could not. It passes from a static and enigmatic form, one that affronts almost with its amplitude, through various stages of lyrical calm, unrest, joyful disturbance, bold peace, to the lovely and, perhaps for White, redemptive release of the final image. ``Frost Wave,'' in scale both microcosmic and macrocosmic, communicates as eternally alive.

White may best be remembered for the intensity of his commitment to photography and for the boldness of his vision. With his teaching and his own creative photography, he asserted the significance of the human and the personal. A number of his images and sequences are among the treasures of 20th century photography.

Retrieved from "Minor (Martin) White." Contemporary Photographers. Gale, 1996. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

http://ic.galegroup.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?displayGroupName=Reference&disableHighlighting=false&prodId=BIC1&action=e&windowstate=normal&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK1653000703&mode=view&userGroupName=tall85761&jsid=60765dd2c812a9f754feb9ce416c96a6 (Accessed Feb. 21, 2012)