Lovis Corinth

Born Tapiau, East Prussia, 21 July 1858; died Zandvoort, Netherlands, 17 July 1925.

German painter and writer. He grew up on his family’s farm and tannery. As a child he showed interest in art, taking informal lessons in drawing from a local carpenter and caricaturing his primary school teachers. Corinth’s father sent him to secondary school in the nearby city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), where he lived with his widowed aunt. A superstitious woman fond of story-telling, she possessed what Corinth later described as a coarse temperament and an unrestrained, ‘demonic’ humour. These qualities and his aunt’s bohemian acquaintances, including fortune-tellers and soothsayers, fascinated the young Corinth, accustomed to his more reserved parents. In this environment Corinth began to develop the rich imagination and love of anecdote that came to play such an important role in the evolution of his art.

In 1876 Corinth entered the Königsberger Kunstakademie. Although he intended to specialize in history painting, he received most of his instruction from the genre painter Otto Günther (1838–84), who apparently convinced him to abandon historicism. Corinth’s few surviving works from this period are soberly observed, if somewhat technically deficient, genre scenes, landscapes and portraits. It was at this time that Corinth began to drink heavily, establishing a lasting pattern that, by his own admission, seriously affected both his health and his art.

When Günther left the academy in 1880, Corinth went to Munich to continue his studies. After only one summer at Franz von Defregger’s private painting school Corinth was proficient enough to enter the Münchener Kunstakademie, where he joined the class of Ludwig von Löfftz (1845–1910) in October 1880. The most prestigious of the academy professors, Löfftz was interested primarily in teaching his students about colour, and so he worked with elderly models whose pale complexions sharpened the students’ powers of observation and trained them to perceive and render in their paintings fine nuances of light and shade. Löfftz’s emphasis on exact tonal transcription encouraged close observation and a factual, unidealized rendering of the model, and Corinth went on to make this working method his own. This essentially Realist approach to subject-matter and the stress on rendering minute variations of tone predisposed the young Corinth to the work of Wilhelm Leibl and Wilhelm Trübner, which impressed him enormously. Corinth’s most successful paintings of this period are broadly brushed, matter-of-fact portraits of elderly, work-worn women (e.g. Old Woman, 1882; priv. col.; see Berend-Corinth, 1958, p. 260). He remained with Löfftz until early 1884, his studies interrupted only by his obligatory year-long military service in 1882–3.

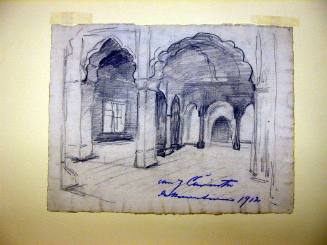

If Corinth learnt about tone and objective observation from Löfftz, Trübner and Leibl, his subsequent teachers taught him the value of draughtsmanship. After three months in Antwerp, where he was particularly impressed by the work of Rubens, Corinth went to Paris in October 1884 and entered the Académie Julian. There, under William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911), his draughtsmanship became tighter and his painterly facture smoother. At this time Corinth also took for a principal subject the female nude, with which he remained preoccupied. He never emulated the waxy, academically idealized nudes of Bouguereau but characteristically retained a realism that even seemed at times to emphasize the more inelegant features of his subjects (e.g. Sitting Female Nude, 1886; see Berend-Corinth, p. 276). Corinth later testified that while in Paris he was unaware of the Impressionists, whose last group show was in 1886. At least one of his paintings was exhibited at the Salon, The Plot (1884; priv. col.; see Berend-Corinth, 1958, p. 276), but by 1887 he had become so discouraged of ever receiving a medal that he returned to Germany, ending his exceptionally long training period of nearly 11 years.

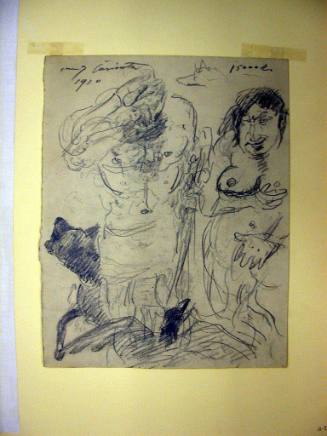

Corinth spent the subsequent years searching for both a home and a style, initially in Berlin (1887–8) and then in Königsberg (1888–91). His father, to whom he was very close, died in 1889, and shortly thereafter Corinth painted his first religious work (Pietà, 1889, destr. 1945). This seems to have awakened in Corinth a love of story-telling possibly inherited from his aunt. From this time on literary subjects—religious, mythological and historical—account for a major portion of his work. His move back to Munich in 1891 intensified these anecdotal tendencies; the novelist Joseph Ruederer lived in Corinth’s building and through him he became friends with the writers Max Halbe, Frank Wedekind and Otto Erich Hartleben, presumably encouraging his literary interests. Many of Corinth’s literary paintings seem to burlesque their academic subjects (e.g. Bacchanal; Temptation of St Anthony, 1897; Munich, Neue Pin.), largely because he did not idealize his models in the manner of more traditional painters but remained committed to transcribing their actual appearance. Regardless of their mythological or religious attributes, Corinth’s figures consistently resemble contemporary German thespians parodying a Classical or Christian play. For many years this dichotomy was criticized, but in the late 20th century it seems evident that Corinth’s tongue-in-cheek comments on academic sentiment are among his most important contributions to the art history of his era.

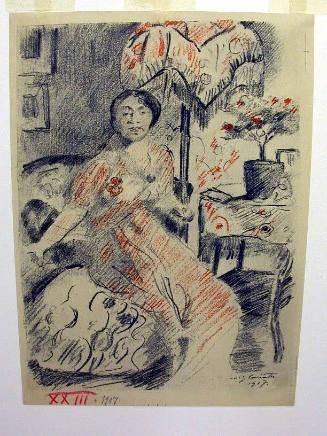

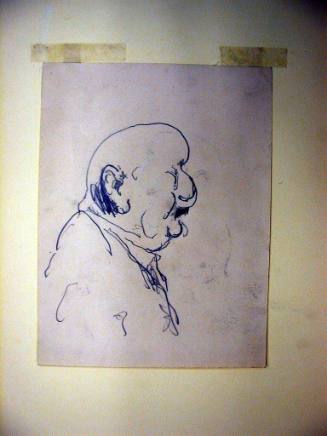

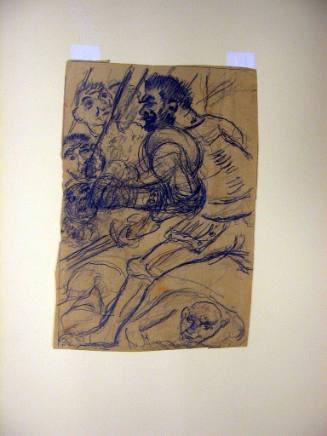

Alongside these literary works, Corinth continued to paint erotic studio nudes and remarkably incisive portraits (e.g. Self-portrait with Skeleton, 1896; Munich, Lenbachhaus), and, under the influence of the plein-air painters Fritz von Uhde and Max Liebermann, he began to paint landscapes outdoors (e.g. Cemetery in Nidden, 1894; Munich, Neue Pin.) and sun-filled interior genre scenes that have often been called ‘Impressionist’. Particularly noteworthy are the paintings of slaughterhouses (e.g. Slaughterhouse in Schäftlarn an der Isar, 1897; Bremen, Ksthalle), in which blood-red carcasses assume a sensually physical presence through Corinth’s use of light and thickly applied pigment. Perhaps no other theme suited so well his bombastic yet erotic aesthetic sensibility. In addition, in an effort to improve his draughtsmanship he began in the 1890s to make prints, a number of which were either preparations for or reworkings of oil paintings.

Despite his growing confidence and talent, Corinth was unhappy in Munich. After resigning from the Secession and the Künstlergenossenschaft exhibition societies in Munich, Corinth found it difficult either to show his work or to build friendships in the Bavarian capital, where his colleagues resented his independence. The Berlin artist Walter Leistikow persuaded him to come to the Reich capital, which he made his permanent home in autumn 1902. The environment proved liberating, not only because he found immediate entry into the art community—he was warmly welcomed by members of the Berlin Secession as an important contributor to their exhibitions—but because cosmopolitan Berlin was far more receptive to the roughness and theatricality of Corinth’s work than was provincial Munich. Although Corinth continued to pursue the same themes, his brushwork became more vehement, his palette brighter and more colourful, and his paint application thicker. His work began to sell, he signed a contract with Paul Cassirer’s gallery, and he established a very profitable art school for women. In 1903 he married Charlotte Berend, a student at his school. Given the inherent theatricality of his work, it is unsurprising that Corinth also collaborated between 1903 and 1905 on set and costume designs for theatrical and operatic productions, including Max Reinhardt’s Pelléas and Mélisande, Salome and Elektra.

In 1911 Corinth suffered a serious stroke, which caused partial paralysis on the left side of his body, a condition complicated by earlier alcohol abuse that had left his right hand shaking badly. The vehemence that had crept into his work after moving to Berlin now intensified, a result of his physical struggle to control the brush. Yet, although both his condition and the state of Germany during and after World War I deeply depressed him, he continued to be enormously productive. Many of his masterpieces were executed during these years. Particularly noteworthy are the series of incisive self-portraits that reflect his continuing preoccupation with his own mortality (e.g. Large Self-portrait in front of the Walchensee, 1924; Munich, Staatsgal. Mod. Kst), and the landscapes of Walchensee in Bavaria (e.g. Tree at Walchensee, 1923; Zurich, Ksthaus), where Corinth and his family spent holidays each year after 1918. In many of these the hurriedly brushed, seemingly windswept and high-keyed pigment assumes a life of its own, quite independent of the objects it delineates. This increased abstraction had particular consequence for the paintings of literary subjects, for a new expressionist urgency wholly consistent with the artist’s emotional state replaced the lightly ironic tone of earlier works (e.g. Birth of Venus, 1923; Düsseldorf, Gal. Paffrath; Ecce homo, 1925; Basle, Kstmus.).

Corinth also spent a considerable amount of time on administrative work for the Berlin Secession: he served on the executive committee for a number of years, and he was elected President in 1915. He was also involved with literary activities, including several book-length autobiographies, a handbook on painting and numerous art-historical essays. He died while on a trip to see for the last time the work of Rembrandt and Frans Hals.

Maria Makela. "Corinth, Lovis." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T019489 (accessed April 27, 2012)