Edward J. Steichen

American, 1879 - 1973

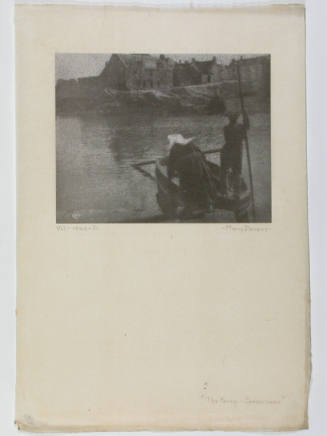

American photographer, painter, designer and curator of Luxembourgeois birth. Steichen emigrated to the USA in 1881 and grew up in Hancock, MI, and Milwaukee, WI. His formal schooling ended when he was 15, but he developed an interest in art and photography. He used his self-taught photographic skills in design projects undertaken as an apprentice at a Milwaukee lithography firm. The Pool-evening (1899; New York, MOMA, see 1978 exh. cat., no. 4) reflects his early awareness of the Impressionists, especially Claude Monet, and American Symbolist photographers such as Clarence H. White. While still in Milwaukee, his work came to the attention of White, who provided an introduction to Alfred Stieglitz; Stieglitz was impressed by Steichen’s work and bought three of his photographs.

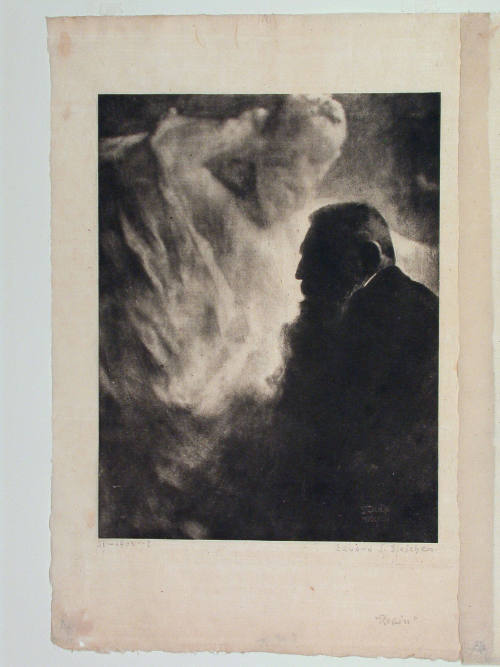

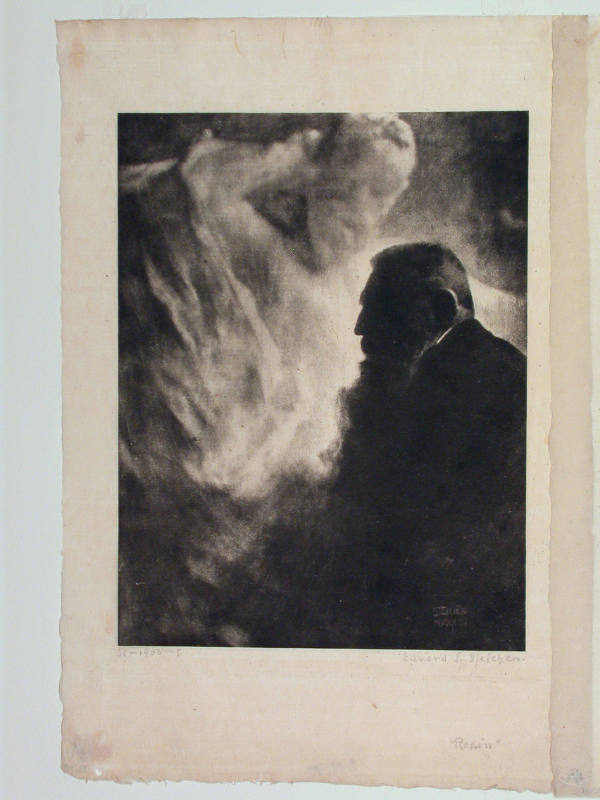

Steichen studied briefly in Paris at the Académie Julian and participated in the New School of American Photography exhibition in London and Paris (1900). He was elected a member of the Linked ring society of British Pictorialist photographers. His homage to Auguste Rodin, Rodin—le penseur (1902; priv. col., see 1978 exh. cat., no. 11), a platinum and gum-bichromate print made from two negatives, is a masterpiece of ethereal form and light, which remains one of his most familiar images. Returning to New York, he became a founder, with Stieglitz, of the Photo-secession group and, in 1903, designed the cover of Stieglitz’s new magazine Camera Work (1903–17). A special edition of his work, The Steichen Book (New York, 1906), was published as a supplement to Camera Work. When he moved from his small studio at 291 Fifth Avenue, he encouraged Stieglitz to use the space as a gallery for new art and photography, and in 1905 it became the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known as 291.

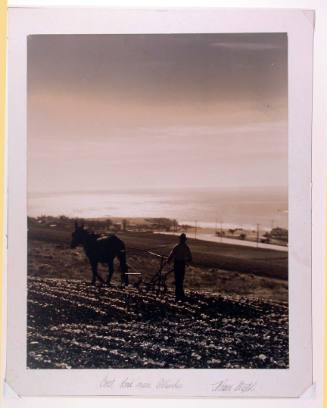

Steichen was still involved in painting as well as photography and abandoned a successful photographic portrait studio to return to Paris in 1906. Through Gertrude and Michael Stein he became acquainted with the most important artists of the Ecole de Paris and arranged, with Stieglitz, for their work to be seen for the first time in the USA at 291. In 1907 he created a series of remarkably delicate colour images within a week of the introduction of the autochrome process by the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis , including Houseboat on the Thames (1907; New York, MOMA, see Steichen, 1963, no. 55).

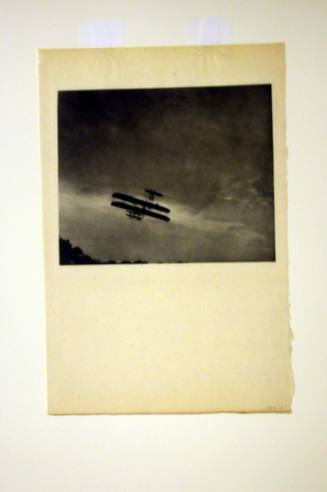

On the eve of World War I Steichen returned to New York. Differing views on the war, the future of 291 and Steichen’s expressed desire to become a photojournalist in the tradition of Mathew Brady severed the close ties that he had with Stieglitz. Steichen first joined the Signal Corps but was then transferred to the US Army Expeditionary Forces Air Service as commander of the photographic division (1917–19). The demand for sharp resolution aerial photographs prompted Steichen to pursue a new interest in photographic technology after the war. His experiments included photographing a white cup and saucer on a series of graduated grey tonal-scale backgrounds and led to compositions such as Pears and an Apple (c. 1921; New York, MOMA, see Steichen, 1963, no. 64), where the lighting techniques he had developed, plus the necessarily long exposures, optically diffused the forms, emphasizing volume and weight. In 1922 he made a final, ceremonial commitment to photography, burning all the paintings remaining in his studio in Voulangis, France.

Although Steichen made several trips to New York during the post-war years, it was not until 1923, when he became Chief of Photography for Condé Nast Publications, that he returned permanently to the USA. He set a new standard for printed photography at Condé Nast. His portraits in Vanity Fair and Vogue defined the era. Gloria Swanson (1924; New York, MOMA) testifies not only to his genius as a designer, with the device of the lace veil, but also to his uncanny ability to convey the essence of the personality before his lens. During his 13 years with Condé Nast he also created advertising images for the J. Walter Thompson agency.

After closing his professional studio in 1938, Steichen began to experiment with 35 mm photography but was halted by the outbreak of war. During World War II he was placed in command of all naval combat photography. In addition he organized two exhibitions for MOMA: Road to Victory (1942), a panoramic portrait of the USA on which he collaborated with his brother-in-law, the poet Carl Sandburg (1878–1967), and Power in the Pacific (1945).

In 1947 Steichen abandoned his own photography and became director of the department of photography at MOMA. Although he organized many exhibitions during his 15-year tenure, he felt that The Family of Man (1955) was his most important contribution. Conceived as a collective portrait, it included 503 photographs by 273 amateur and professional men and women from 68 countries. It could be argued that The Family of Man was a social document that found its way into the annals of art through the prestige and position of its curator, yet it became, in its travels throughout the world, one of the most popular exhibitions ever held.

In 1961 MOMA presented a retrospective exhibition of Steichen’s work, naming the department of photography in his honour; he retired from the department in July 1962. Among his last projects before retiring was a series of 35 mm colour photographs, the Shad-blow Tree (New York, MOMA, see Steichen, 1963, nos. 243–8), devoted to his meditations on a flowering tree outside his home in Connecticut.

Retrieved from Oxford Art Online; http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081198?q=Edward+J.+Steichen&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit (Accessed Feb. 16, 2012)

Person TypeIndividual

American, born Polish, 1899 - 1968