Ganku

Born Kanazawa, 1749 or 1756; died Kyoto, 1838.

Japanese painter. Two different dates are recorded for his birth, and his father’s identity is unclear, as are other details of his early life. Ganku was said to have been initially self-taught: he learnt to read from shop signs and to paint by copying textile patterns in the dyeing shop where he was employed. Various sources suggest that he later studied painting with local artists Yada Shinyo-ken and Mori Ransai (?1740–1801), although, according to records left by his son, Gantai (1782–1865), Ganku himself professed to have studied only Chinese paintings.

Ganku left Kanazawa for Kyoto in 1779 or 1780 to further his artistic career in the imperial capital, home to many of Japan’s most original painters of the day, including the founder of the Maruyama school of naturalistic painting, Maruyama o-kyo, and two ‘eccentric’ individualists, Soga Sho-haku (see Soga, (2)) and Ito- jakuchu-. Chinese cultural and philosophical influences abounded in Kyoto. Artists sought to break free of Chinese and Japanese tradition, as expressed in the paintings of the Kano- and Tosa schools, in favour of a radical brand of Neo-Confucianism and its spirit of ki (eccentricity, strangeness or the possession of superior intellect)—an outgrowth of Daoist influence—which encouraged artistic creativity and placed an individual’s personality above issues of technique and lineage. Ganku easily absorbed elements of the prevailing art trends. From the literati painters such as the late Ike Taiga, he took a lively, calligraphic brushwork, which he imbued with a nervous, choppy rhythm. From O-kyo he took a rationally based naturalism, and from Jakuchu- some of the meticulous Nagasaki-school manner. Moreover, his paintings exhibit such close stylistic indebtedness to those of the Chinese painter Shen nanpin (a founder of the Nagasaki school) that earlier scholars assumed he must have studied with a follower of Shen or had access to Shen’s paintings. Scholarship now suggests that Ganku’s Chinese sources were broader, and that he also incorporated elements of the Kano- school and Western-style Japanese painting (Nanban art; see Japan, §VI, 4(vi)(a)). Legendary for his forceful and arrogant personality, Ganku by all accounts became an immediate success in Kyoto’s highly competitive art market. His name was recorded in the Heian jinbutsushi (‘Record of famous personalities of Heian [Kyoto]’) as soon after his arrival as 1782. Ganku sometimes collaborated with the prominent Kyoto painters with whom he was acquainted, for example Matsumura goshun, founder of the Shijo- school (e.g. Sansui zu; ‘Pictures of landscape’; 1796; Tokyo, Sch. F.A.).

Ganku came to the attention of Prince Arisugawa, who appointed him as retainer in 1784 and conferred on him the art name (go-) of Utanosuke. This official recognition enabled him to secure private commissions, and Ganku soon became wealthy. In 1808 he was appointed honorary governor of Echizen with the title Echizen no Suke. In the following year he was invited to Kanazawa to create wall paintings for Kanazawa Castle. He was by now at the height of his career, and his paintings sold for as much as works by the best painters of Kyoto, including those of O-kyo. Most extant works by Ganku date from after this time. In 1824 Ganku retired to Iwakura in northern Kyoto. In 1837 he was promoted to the rank of Echizen no Kami. He is buried at Hozenji in Kyoto, a temple of the Nichiren sect, with which he was affiliated.

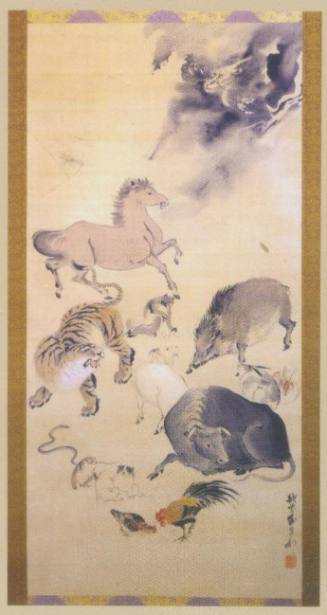

Ganku painted a wide variety of subjects: landscapes, portraits, birds-and-flowers (kacho-ga) and animals. He and his followers became most famous, however, for paintings of tigers. His best-known work of this subject is a pair of two-panel folding screens (1823; Tokyo, N. Mus.). Like other Japanese painters who portrayed these beasts, Ganku never saw a live tiger and had to imagine the living animal from imported skins; but he did own a tiger’s head, which had been imported via Nagasaki and presented to him in 1798. To commemorate the gift, he began using the art name Goto-kan (Tiger’s Head Hall). Among his many commissions are wall paintings of Geese and Pines (Gansho- zu) for the palace (Sento- Go-sho-) of the retired emperor in Kyoto (1816), paintings of the Three Laughers of Tiger Valley (Kokei sansho- zu) for a tea house at the Shu-gakuin Imperial Villa (1824) and a ceiling painting of Dragons (Tatsuzu) for the Kannondo- of To-ji temple (1826).

For many Kyoto artists fame was fleeting. The detailed Chinese-style paintings at which they excelled went out of fashion late in the 19th century. By the mid-19th century Ganku’s reputation was already on the decline. However, changes in taste, particularly in the West, in the second half of the 20th century, have brought renewed popularity to Ganku’s bravura brushwork and naturalistic portrayals of animals. Outstanding among his many pupils were his son and successor, Kishi Gantai, his nephew, Kishi Ganryo- (1797–1852), his son-in-law and adopted son, Aoki Renzan (1805–59), and Yokoyama Kazan (1784–1837). The most famous successor of his school was Renzan’s son and pupil, Kishi Chikudo- (1826–97), who carried the Kishi tradition into the modern period.

Patricia J. Graham. "Kishi Ganku." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T046728 (accessed May 8, 2012).