Utagawa Hiroshige I

Born Edo [now Tokyo], 1797; died Edo, 1858.

Japanese painter and printmaker. He was one of the greatest and most prolific masters of the full-colour landscape print and one of the last great ukiyoe (‘pictures of the floating world’) print designers (see Japan, §IX, 3(iii)). A master of colour and composition, Hiroshige won popularity and lasting fame for his sensitive and atmospheric designs.

1. Early development, before 1818.

Hiroshige was the eldest son of a samurai, a minor official associated with the shogunal fire department. As a child Hiroshige showed skill in drawing and seems to have aspired to become an artist. He was first apprenticed to O-kajima Rinsai, a minor member of the Kano- school, from whom he learnt the elements of brushwork and composition. His brushwork became freer and more spontaneous when he studied under O-oka Unpo- (1765–1848), a painter in the Chinese style, who also taught him the importance of atmosphere. Independently, Hiroshige experimented with the naturalistic and Western-influenced styles of the Nagasaki and Shijo- schools (see Japan, §VI, 4(vi)(c) and (viii)). By the age of 14 or 15, Hiroshige had decided that the ukiyoe genre held the most appeal for him, and he applied to become a pupil of Utagawa Toyokuni (see Utagawa, (2)), a master of the largest and most powerful school of ukiyoe. Toyokuni being overstretched, Hiroshige was assigned instead to Toyohiro (see Utagawa, (4)), whose work was characterized by the lyrical charm for which Hiroshige later became famous. In 1812, after only a year’s apprenticeship, Hiroshige graduated from Toyohiro’s studio. He took the name Utagawa Hiroshige as token of his affiliation with the school, although within a few years he had broken his ties with it, and in 1818 he made his debut as a serious print designer.

2. 1818–48.

Hiroshige did not immediately begin to produce landscape prints. From about 1818 to 1830 his main output consisted of inimitably individualistic prints of beautiful women (bijinga) and actors ( yakushae), a speciality of the Utagawa masters. At the same time he tried his hand at surimono (‘printed things’; deluxe prints) and book illustrations, of which many examples exist. These were executed in the plain, uniform style he had inherited from Toyohiro and proved over time less popular than the figurative subjects depicted by Hiroshige’s rivals Kunisada and Kuniyoshi (see Utagawa, (5) and (6)).

It was a time of discontent for Hiroshige, who, by constant trial and error, was seeking his own artistic style. It was also a time when both ukiyoe and the print movement were flagging: new ideas and subjects were rare and execution lacklustre. Landscape, which had been out of favour for some years, being regarded as too traditional and, perhaps, too highbrow for the print-buying public, was returning to popularity and in so doing giving print production a new lease of life. This process received a boost from the publication of Katsushika hokusai’s Fu-gaku sanju-rokkei (‘Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji’). Hiroshige too became aware of the possibilities of the landscape print, and c. 1826 he released the series To-to meisho (‘Famous views of the eastern capital’; e.g. Amsterdam, Rijksmus.), a simple landscape series which illustrated the various sites in Edo. It met with very favourable criticism. This series was unusually coloured, successfully employing the pink pigment derived from safflower and indigo blue. It was apparently issued to rival Hokusai’s work but was wholly different in character. Hiroshige’s were frank and refreshingly true-to-life sketches as seen through the eyes of an inhabitant of Edo, not vain displays of personal eccentricity.

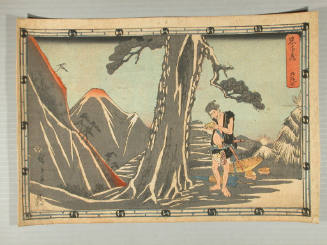

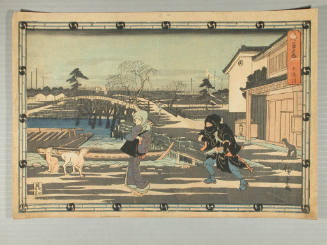

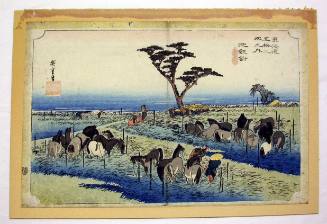

Sent on a shogunal delegation to Kyoto in 1830, Hiroshige travelled along the Tokaido, the eastern sea road. The activity on the road and the surrounding scenery made a deep impression on him, and in 1833–4 he published the sequential series of 55 single sheet prints, the To-kaido- goju-santsugi no uchi (‘Fifty-three stages on the Tokaido’, Tokyo, N. Mus.), supervising the production personally. The images were based on his own sketches of views that touched him, but in technique also hinted at the compositions in an earlier published collection of famous views of the Tokaido. Using such elements as the wind, rain or snow, the moon and flowers, the pictures achieved a subtlety that struck a chord with the innermost sentiments of the Japanese. The compositions overflow with beautiful and sensitive observations. Earlier periods in Japanese history had yielded many examples of sansuiga (‘mountain-and-water pictures’; landscapes) and fu-keiga (natural scenes), but Hiroshige’s series was without doubt a work of outstanding novelty and enduring merit. The series was a resounding success, and Hiroshige became the Japanese landscape artist par excellence, socially on an equal footing with other famous print designers of the period. The success of the Tokaido series encouraged Hiroshige to become increasingly a true landscapist. He executed such print series as the Kiso-kaido- rokuju-kyu-tsugi (‘Sixty-nine stations on the Kisokaido’, c. 1839; e.g. Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and the better-known environs of the provinces or of large cities such as Edo and Kyoto, for example O-mi hakkei no uchi (‘Eight views of Lake Biwa in O-mi Province’; c. 1834) and the Kyoto meisho (‘Famous views of Kyoto’; 1834; e.g. Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). A huge number of landscape prints were constantly being released by different publishers; prolific though he was, Hiroshige designed only a small proportion. At the same time, he was trying his hand at prints of birds and flowers and in this field too he competed with Hokusai. For these works he used principally an adapted long compositional format such as that of tanzaku(ban) (poem cards, narrow strips of paper, c. 300 mm long). Unlike Hokusai, he did not intend to include text. The lyricism, intimacy and harmony of his landscape prints are also manifest in these bird-and-flower works, in which the brushwork seeks to represent both the rich splendour and the tranquillity of nature. He also experimented with such new devices as the combination of beautiful women and landscapes.

3. 1849 and after.

In 1849 Hokusai died, leaving the field of landscape prints principally to Hiroshige, Kunisada and Kuniyoshi. For the next four or five years, however, Hiroshige’s enormous productivity (his total output is estimated at 5000 designs) took its toll of artistic quality and inspiration. His works became mediocre and repetitive, partly as a result of a decline in demand from publishers for pure landscape designs. It was not until about 1853 that he began again to produce works of note and quality. From the period 1853–8 date compilations of intimate landscape prints in vertical format, such as the Rokuju- yoshu- meisho zue (‘Famous places of the sixty provinces’; 1853; e.g. Amsterdam, Rijksmus.) and the Meisho Edo hyakkei (‘One hundred famous views of Edo’; 1856–8; e.g. New York, Brooklyn Mus.). In two or three works he defied the conventional large triptych format.

The later works lack the sensitivity and easy grace of those produced at the peak of his output in the 1830s and early 1840s. On the other hand, Hiroshige also produced a number of nikuhitsuga (ukiyoe paintings) in his later years. These were notable for their elegant simplicity and their capacity to reveal the artist’s inner character. The light brushwork was adept and skilful, producing compositions full of charming artistic effects. In this genre the enormously talented Hiroshige towered above his rivals.

From the Bakumatsu (‘end of the shogunate’) period (1853–68) date many great works by Hiroshige, most of them ukiyoe prints rather than paintings. Hiroshige’s abilities unfolded pari passu with the development of the polychrome print (nishikie), which was a collaborative art involving the print designer, carver and printer. While the craftsmen served the print master in the interpretation and rendition of his designs, he in turn knew how to take optimum advantage of the techniques of cutting and printing, incorporating great strength of expression into his exquisite designs. Of particular use to him was the bokashi (‘gradation or shading’) technique, one of many technical innovations that permitted the full splendour of his meishoe (‘pictures of famous places’) to be revealed. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that Hiroshige owed his greatness and success to the development of the nishikie.

Hiroshige died two years after his retirement, and is buried in a Zen temple in Asakusa, Tokyo. His work is imbued with candour, genuineness, humility, a deep love of the landscape and sensitivity, all reflections of his gentle and genial character. Some of its special traits—the turbid, deep background plane, for example—are a function of his identity as a resident of Edo, influenced by its artistic traditions and responding to the requirements of its publishers and markets. While some artists, such as those of the Maruyama–Shijo- school (see Japan, §VI, 4(viii)) associated with each other and developed a broader outlook, Hiroshige stood apart. Yet, paradoxically, it was he who captured in his work a universality of experience and sentiment. He had few pupils, and they proved relatively undistinguished; the last was Hirokage ( fl 1851–66). Nevertheless, Hiroshige significantly influenced European, especially French, artists from the 1870s onwards: his shadowless drawing, mastery of telling detail, starkly geometric compositions, and above all the overall ‘arrangement’ of form were emulated by van Gogh, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Monet and Manet, among others. The American painter Whistler also borrowed elements of Hiroshige’s style.

Masato Naito-. "Ando- Hiroshige." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T002710 (accessed May 8, 2012).