Image Not Available

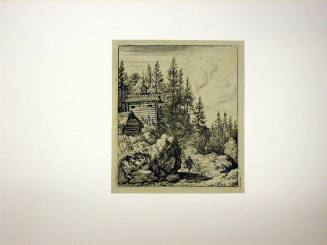

for Meindert Hobbema

Meindert Hobbema

Dutch, 1638 - 1709

Dutch painter. Although limited in subject-matter and working from a remarkably narrow repertory of motifs and compositional devices, he nonetheless managed to imbue his area of specialization—the wooded landscape—with memorable vitality.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early career, before 1663.

The son of Lubbert Meyndertsz., a carpenter, Meindert adopted the surname ‘Hobbema’ at an early age, although it appears to have had no family precedent. In 1653, together with his younger brother and sister, he was taken into the care of the Amsterdam orphanage. Two years later he had left this institution, and it was then, or shortly after, that he entered the studio of the Haarlem landscape painter Jacob van Ruisdael, who had recently moved to Amsterdam. On 8 July 1660 Ruisdael testified that Hobbema had ‘served and learned with him for some years’. In spite of his period of apprenticeship with Ruisdael, Hobbema’s paintings from the 1650s are river scenes that show the impact of Cornelis Vroom and Salomon van Ruysdael. His earliest dated work is a View of a River (1658; Detroit, MI, Inst. A.). This modest painting, executed when the artist was only 20, reveals a tranquil setting with a diagonally slanting riverbank along which slender, insubstantial trees, cottages and several figures are placed at gentle intervals. It is broadly painted with muted greens, browns and greys. The general composition of the painting, in particular the silhouetting of the somewhat awkward trees against a light sky, is reminiscent of Salomon van Ruysdael’s works of the mid-1650s.

Around 1662 the influence of his famous master Jacob van Ruisdael became markedly visible in Hobbema’s work. In particular, a number of landscapes with water-mills from this year take their central motif and other elements from Ruisdael’s Water-mill (1661; Amsterdam, Rijksmus.). A typical example of Hobbema’s dependence is Landscape with Water-mill (Toledo, OH, Mus. A.), undated but evidently painted during 1662, which is an almost exact copy of Ruisdael’s painting. Hobbema’s touch, however, is broader and his tones brighter, especially in the light-filled middle distance; the melancholic, more brooding quality that infuses Ruisdael’s work with so much mystery is absent.

(ii) Middle period, 1663–8.

The period of close alignment with Ruisdael was short-lived. Hobbema’s later paintings from the 1660s, which are on a larger, more ambitious scale, show a greater spatial clarity and expansiveness, a more fluid touch and a heightened sense of colour. The years between 1663 and 1668 were the most productive in his career. In his Wooded Landscape: The Path on the Dyck (1663), the strong vertical accent of the central cluster of spindly trees with their lacy foliage is relieved by the two pathways, which plunge in diverging directions and on plateaux of varying levels into the distance. This double vanishing-point is frequently repeated in Hobbema’s work and gives his compositions a feeling of freshness they would otherwise lack. By reducing the horizon line, greater emphasis is given to the sky with its huge billowing clouds, which echo the sprawling mass of trees and shrubbery below. His palette is full of subtle variations of bright green, yellow, grey and brown, which produce an overall silvery tonality. Also characteristic of Hobbema is the shaded foreground, with occasional flickers of half-light that lengthen the cast shadows of figures and cows and contrast with an area of intense light in the background. As with much of Hobbema’s work, this painting gives the impression that although he has taken his original inspiration from nature, his final conception is formed by a desire to present landscape as an idyllic environment, ordered and regulated by man. The staffage was painted by Adriaen van de Velde, who often collaborated with Hobbema.

In a number of paintings from c. 1665, among them The Water-mill (London, Wallace), Hobbema returned to a theme with which he is closely associated. The subject of the water-mill was a particular favourite of Hobbema and he painted it on over 30 occasions. Variously interpreted as a symbol of the transience of human life and as a wonder of modern industry, it is difficult to determine with certainty what associations the water-mill evoked for a contemporary audience. A number of Hobbema’s landscapes have also been shown to be representations of actual mills found on the estate of Singraven near Denekamp in the province of Overijssel, and he may have accompanied Ruisdael on a sketching trip to this area. The specific mill in the above-mentioned painting and that in a close variant (Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) have not been identified. Unlike his earlier paintings of this subject, which were closely based on Ruisdael, the water-mill is placed less conspicuously in the middle distance and flooded by a brilliant light that spreads to the distant prospect glimpsed through the slender tree-trunks and feathery leafage.

With the Wooded Landscape (1667; Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.) the beginning of a new period of restraint and stillness can be detected. A greater freedom of brushstroke is apparent also, and foliage that was previously more precisely delineated is now summarily indicated. The juxtaposition of a darkened foreground, where shadows shimmer on the glassy surface of the water, with the sunlit fields beyond, greatly accentuates the sense of distance. The lively figures punctuating the banks of the pool, together with the billowing clouds and soaring birds, successfully create the impression of a wild and blustery day. In his Forest Pond (1668; Oberlin Coll., OH, Allen Mem. A. Mus.), Hobbema created an even more simplified composition with less elaborate trees carefully placed around a gently rippling brook. Also noticeable is the sketchy manner in which the grass and vegetation in the right foreground is painted. The mood here is again one of calm, achieved through a harmonious distribution of the pictorial elements.

Townscape is a rarity in Hobbema’s oeuvre and the View of the Haarlem Lock and the Herring-packers’ Tower, Amsterdam (London, N.G.) is his only widely accepted work in this genre. This marvellously vivid glimpse of Amsterdam canal life is an accurate portrayal of one of the city’s principal sluice-gates and surrounding architecture. Although it has been dated to before 1662 (since it is known from later topographical sources that alterations were made to some of the buildings in that year), it is much more likely on stylistic grounds to have been executed in the latter half of the decade.

(iii) Late works, 1668–1709.

In October 1668, Hobbema married Eeltje Pieters Vinck, four years his elder and kitchen-maid to the Amsterdam burgomaster Lambert Reynst. Hobbema must have maintained his links with his teacher during these years, as Ruisdael acted as a witness to the marriage. At this time also, Hobbema became a wine-gauger to the Amsterdam customs; this was a minor salaried post (which he held until his death), involving the supervision of the weighing and measuring of imported wines. It was long thought that Hobbema all but ceased to paint after his marriage and his subsequent municipal appointment. However, a revised reading of previously accepted dates on a number of established paintings and the discovery of new works has resulted in the reassessment of a small body of late landscapes. Nevertheless, it is apparent that Hobbema’s activity as a painter greatly declined after 1668, and there are no certain paintings from the last two decades of his long life.

A decline in his artistic powers is also discernible in some of these late works. His painting of the Ruins of Brederode Castle (1671; London, N.G.), a picturesque structure near Haarlem that had suffered great damage in the Eighty Years War, lacks the inventiveness of earlier designs and is contrived in appearance. The trees that frame the ruined castle on a hill in the middle distance are thin and lifeless, their outlines brittle against a pale sky. There is a lack of modulation in the painting of the ruins and the general effete approach is emphasized by the awkward variations in tone and harsh colouring. The ducks, placed prominently in the foreground, are by a different hand, probably that of Dirck Wijntrack (before 1625–78). However, Hobbema still had one last ace to play, and his best-known work from these later years is the Avenue of Trees at Middelharnis (1689). Hobbema’s conception of a tree-lined avenue with a view of a distant town beyond receding perpendicularly from the picture plane is markedly in contrast to similar landscape compositions by Aelbert Cuyp and Jan van Kessel, a fellow pupil of Ruisdael with whom Hobbema is known to have remained in contact. Greater spaciousness is achieved by minimizing the number of trees to two slender rows that define both the depth and the height of the composition. The painting differs from other 17th-century Dutch landscapes not only in its highly organized and symmetrical design but also in the inclusion of a gardener actively engaged in tending saplings. Indeed, attention has been drawn to the contrast between the more rugged view of nature on the left and the nurtured plantation in the right foreground. Hobbema’s final years must have been difficult, not only financially but also because he had to endure the deaths of his two children and that of his wife in 1704. He was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Hobbema was also apparently active as a draughtsman, although no signed drawings by him are known. Giltay has attributed a group of seven drawings to him, including five of water-mills. Given the paucity of surviving work by Hobbema in this medium compared to other 17th-century Dutch landscape artists, preparatory drawings may only have played a minor part in his working method.

2. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

To judge from the few followers he attracted and from his failure to receive even a brief mention by Arnold Houbraken, Hobbema’s achievements as painter must have been overlooked by his contemporaries. His name seldom appears in 17th- or 18th-century auction catalogues and his work often realized quite low prices. Indeed, it was well into the 19th century before he was rescued from obscurity; as late as 1859 the French art historian Théophile Thoré [pseud. Willem Bürger], who did much to rekindle interest in overlooked Dutch masters, bemoaned the lack of appreciation of Hobbema. However, it was in England in the second half of the century that the taste for Hobbema, and for his master Ruisdael, reached new heights, stimulated in part by the praise heaped on naturalistic Dutch landscape painting by artists such as Turner and Constable. Earlier, Hobbema had also been held in great affection by the Norwich school of landscape painters, especially by John Crome, whose Poringland Oak (London, Tate) recalls the work of the Dutch master in its treatment of a gnarled oak against a glowing sky with vistas into the distance. The collecting of Hobbema’s work also grew apace during these years, and in 1850 at The Hague, Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford, paid what was then a record price for a landscape when he bought The Water-mill (London, Wallace) for 27,000 guilders.

John Loughman. "Hobbema, Meindert." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038372 (accessed May 8, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual