Richard-Parkes Bonington

Born Arnold, nr Nottingham, 25 Oct 1802; died London, 23 Sept 1828.

English painter. His father, also called Richard (1768–1835), was a provincial drawing-master and painter, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and the Liverpool Academy between 1797 and 1811. An entrepreneur, he used his experience of the Nottingham lace-manufacturing industry to export machinery illegally to Calais, setting up a business there in late 1817 or early 1818. In Calais the young Richard Parkes Bonington became acquainted with Louis Francia, with whom he consolidated and expanded whatever knowledge of watercolour technique he had brought with him from England. Under Francia’s direction Bonington left Calais for Paris where, probably not before mid- or late 1818, he met Eugène Delacroix. The latter’s recollection of Bonington at this time was of a tall adolescent who revealed an astonishing aptitude in his watercolour copies of Flemish landscapes. Once in Paris Bonington embarked on an energetic and successful career, primarily as a watercolourist. In this he was supported by his parents who sometime before 1821 also moved to Paris, providing a business address for him at their lace company premises.

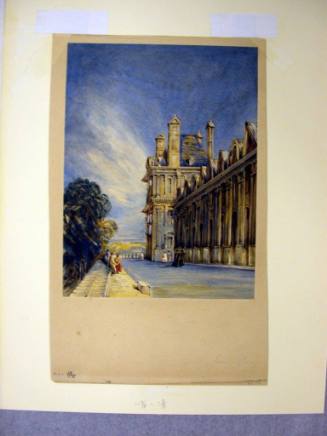

In Paris in 1818 Bonington enrolled at the atelier of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, whose reputation was that of a skilled colourist and a progressive teacher. Bonington mastered the art of drawing à la bosse, as can be seen from the pencil and black chalk Faun with Pipes (New Haven, CT, Yale Cent.) and, in common with all Gros’s pupils, engaged in plein-air sketching. From an early age Bonington was an extremely accomplished watercolourist as is revealed, for example, in his View of Calais from La Rade (c. 1818; Paris, Bib. N.; see also View of Rouen from St. Catherine’s Hill), and he did much to encourage the vogue for the medium in the 1820s and 1830s among young Paris-based artists, from Ary Scheffer and Delacroix to Charles Gleyre and Gericault. He exhibited views of Lillebonne and Le Havre (untraced) at the Salon of 1821. Bonington left Gros’s atelier in 1822; the teacher, after having been struck by the brilliant watercolours of his young pupil in a dealer’s shop-window, declared: ‘That man is a master.’

From that moment until his death six years later, Bonington was constantly on the move. He travelled the coasts of northern France and worked in Paris for the engraver J. F. d’Ostervald on the second volume of Baron Isidore-Justin-Severin Taylor’s Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France (1825). He painted watercolours of the château of Rosny (1823–4; London, BM), which belonged to the anglophile Caroline, Duchess of Berry, and also travelled along the Seine, making numerous watercolour studies. He spent the spring and summer of 1824 in Dunkirk with Alexandre Colin (1798–1875). Here he visited members of the Morel family, to whom he had been introduced by Francia. The stay is recorded in a series of memorable pencil portrait studies of Bonington by Colin (Paris, Carnavalet), and also in a sequence of humorous pseudo-medieval letters by Bonington. While at Dunkirk he sketched at sea in a boat and must also have visited nearby Bergues and St Omer, whose ruined abbey appears in a number of his works. A sheet of small watercolour studies after Gerard ter Borch the younger, Rubens and others (Paris, Fond. Custodia, Inst. Néer.) shows how in Paris, during the winter months, Bonington supplemented his taste for Troubadour style painting (fanciful, mysterious and evocative recreations of historic interiors and balcony scenes) by freely copying Old Masters in the Louvre.

In 1825 Bonington went to London with several French artist friends including Delacroix, where they visited Westminster Hall and Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick’s collection of medieval armour. The fruits of this study can be seen in Delacroix’s Murder of the Bishop of Liège (1827–9; Paris, Louvre) and Bonington’s Quentin Durward at Liège (Nottingham, Castle Mus.), both of which are based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel Quentin Durward. With a letter of introduction from Francia to J. T. Smith, Keeper at the British Museum, Bonington and Colin were able to see the Elgin marbles; they also visited Carl Aders’s collection of German and Flemish primitives. Following their return to Paris, Bonington and Delacroix shared a studio for a brief period, producing similar works, which were orientalizing or medievalizing in style and content.

In 1826 Bonington visited Venice in the company of Baron Charles Rivet. They travelled through Switzerland to Milan (where Bonington produced a dramatic watercolour of the interior of the church of S Ambrogio; London, Wallace) and then continued on to Bologna and Verona. Their visit profoundly affected Bonington, although Venice was not at this time a popular location among artists. Samuel Prout and Turner had visited the city before he had, but Bonington was the first to exhibit his oils publicly, showing View of the Piazzetta and the Ducal Palace, Venice (London, Tate) at the British Institution and the Royal Academy in 1828. Yet these oils, among them the Piazza San Marco, appear laboured in comparison with the sparkling spontaneity and versatility of handling (ranging in treatment from liquid washes to dry brushstrokes) of his Italian watercolours such as The Piazzetta, Venice.

In Venice Bonington had the opportunity of studying the work of Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese at first hand. His debt to them is evident both in the subject-matter and colour range of his Troubadour paintings, such as the oil version of Henry IV and the Spanish Ambassador (exh. Salon 1827–8; London, Wallace). These pastiches were constructed from various sources: his familiarity with the work of van Dyck and Titian, his readings of Brugière de Barante and medieval chronicles, and his visits to the Paris theatres of the 1820s. Brilliantly executed, these small-scale fantasies parody and undermine the established meanings of historical pictures by artists such as Ingres and Paul Delaroche. The term Ecole Anglo-Venetienne was coined by Auguste Jal in 1827 to describe works in this vein. This was a school that appealed not only to Delacroix (who told Bonington: ‘Vous êtes roi dans votre domaine et Raphael n’eût pas fait ce que vous faites’) but also to a variety of aristocratic collectors, such as Henry Fox, 3rd Baron Holland, and John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, in England, and Comte Turpin de Crissé in France. Bonington’s most enthusiastic collector, however, was the Bordeaux wine-merchant John Brown, who acquired an outstanding collection of the artist’s watercolours, a substantial part of which is now preserved in the Wallace Collection, London.

Bonington’s career was suddenly and tragically cut short when he died of consumption at the age of 26. The brevity and brilliance of his working life have encouraged a sentimental appreciation of his work and a tendency to isolate him from such peers as Paul Huet, Alexandre Colin, Thomas Shotter Boys and the Fielding brothers.

Marcia Pointon. "Bonington, Richard Parkes." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T009888 (accessed May 1, 2012).