Howard Kanovitz

American, born 1929

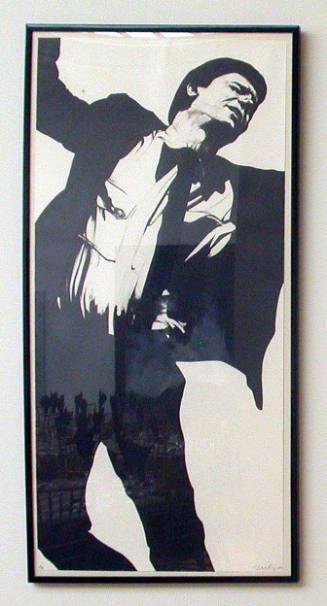

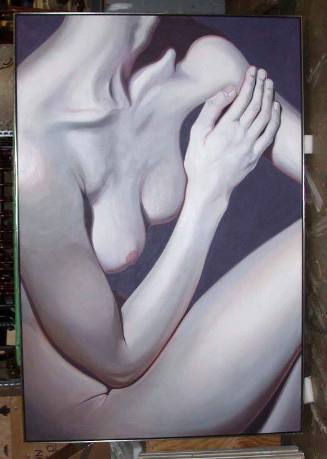

The art historian Sam Hunter described how Kanovitz’s “meticulous airbrush technique and exactness of vision produce an atmosphere of doubt rather than certitude and posed questions of meaning which challenge the very nature of the artistic experience.” (2)

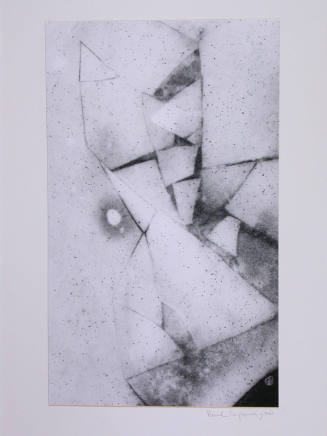

After moving to New York City in the 1950s Kanovitz worked as the assistant to Franz Kline. He quickly became part of the downtown abstract expressionist scene, exhibiting works at the fabled Tenth Street galleries*, the Tanager and Hansa, and in the Stable Gallery annuals, where he had his first one-man show in 1962.

Even during the years when Kanovitz was receiving laudatory reviews for his abstract work, Kanovitz always painted privately with an interest in the figure and new ways to explore the illusion of form in space on a flat canvas. In 1963 after the death of his father, while pouring over family photographs, Kanovitz had a Roland Barthes-like, punctum moment, that solidified his interest in the nature of representation and the complex relationship between subjectivity, meaning, and memory. He began using photographs as source material, either appropriated from the media or taken himself.

In 1972, the Americans Chuck Close, Richard Estees, and Howard Kanovitz were chosen to join Europeans Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Malcolm Morley, and Franz Gertsch, in Harald Szeeman’s groundbreaking international art exposition Documenta* V, held in Kassel Germany, as the pre-eminent exponents of this new photo based painting. He also represented America In Documenta VI, 1977.

In 1979 Kanovitz was awarded the prestigious DAAD fellowship to live and work in Berlin, where he had a mid-career retrospective of over 200 works at the Akademie der Kunst, which then traveled to the Kestner Gesellshchaft, Hannover. He taught at the Salzburger Summer Art School, founded by Oscar Kokoschka, as well as at The School of Visual Arts* in New York, and took on stage design projects in both America and Germany.

In addition to the three one person museum exhibitions already cited, and one at Museum of Contemporary Art in Utrecht, Kanovitz had more than fifty one person gallery exhibitions including the Waddell, Stefanotty, Alex Rosenberg, and Marlborough galleries in New York, the Gana Art Gallery in Seoul Korea, and the Jollenbeck, Inge Baecker and Ulrig Gering Gallery in Germany where he had his last one person show in 2008, one year before he died. He participated in over 100 group shows in America and Europe.

Written and submitted by Carolyn Oldenbusch, wife of the artist.

Howard Kanovitz, 79, Who Recreated the Real, Dies

By BRUCE WEBER

Published: February 9, 2009

Howard Kanovitz, a pioneer of the Photo Realism style of painting, which emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against abstraction in general and Abstract Expressionism in particular, died last Monday in Manhattan. He was 79 and lived in Southampton, N.Y.

The cause was a bacterial infection after heart surgery, said his daughter, Cleo Cook.

Rather than entirely deconstructing or obliterating the recognizable in their painted imagery, the Photo Realists sought nearly, but not quite, to recreate the real and thus suggest an ambiguity between that and what is imagined. They drew on actual photographs as research for their paintings, sometimes as virtual blueprints, and presented their images with photographic detail.

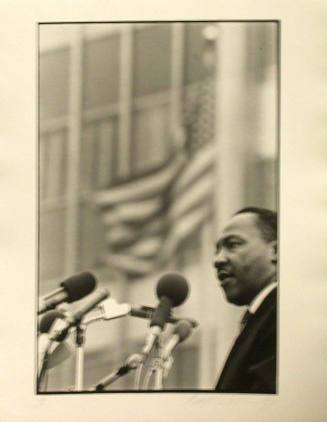

Mr. Kanovitz’s technique was to project photographic images onto a canvas and paint over them, allowing them to guide the work in composition and scale. Works presented in his first solo show as a Photo Realist, at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan in 1966, put him at the forefront of a movement that gathered momentum in the next several years and included Chuck Close, Ralph Goings and Richard Estes.

“His influence was that he made working from photographs seem like a good idea,” Mr. Close said in an interview on Wednesday.

Often misunderstood as photographic replication, Photo Realism was actually more about questioning what is thought of as reality than about representing it. In a signature work called “The Opening,” (1967), for example, Mr. Kanovitz painted a gallery-show opening attended by prominent members of the New York art scene — painters, critics, curators and the like — all of whom would be recognizable to visitors at the gallery where the painting was being shown, and whose images were drawn from photographs taken at actual art openings. As a companion piece, he created stand-alone canvases of individual people (also from images snapped at openings) who are seen gazing at the painting, an implicit query into the relationship between looking and being looked at.

Howard Earl Kanovitz was born in on Feb. 9, 1929, in Fall River, Mass., where his father was a clothing manufacturer. He graduated from Providence College and later spent two years at the Rhode Island School of Design; he also studied art history at New York University. As a painter, Mr. Kanovitz was a student of Franz Kline, and his early work, in the 1950s, was in the Abstract Expressionist mode, the non-geometric, emotion-infused style favored by Kline, Jackson Pollock and others, which he came to see as a stifling trend. He broke away from it in the early 1960s.

“It was an orthodoxy, like a religion,” he recalled in a 1969 interview with Grace Glueck in The New York Times. “You were into it or you were out.”

Mr. Kanovitz actually grew up not wanting to be a painter at all but a musician. Before becoming an artist he played the trombone professionally, including a stint in Gene Krupa’s band. He continued to play throughout his life, often in the company of his friend and fellow painter Larry Rivers, who played credible saxophone, in a group known as the East 13th Street Band.

Along with Rivers, Mr. Kanovitz was among the coterie of writers, artists and musicians that made Greenwich Village and the east end of Long Island the unofficial capital of hip in the 1950s and 1960s.

Willem de Kooning, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch and Terry Southern were among his compatriots, hanging out in places like the Cedar Tavern on University Place in the Village, where the drinks flowed voluminously and the fierce banter was about jazz, books and art.

His first marriage, to Mary Rattray, ended in divorce. In addition to Ms. Cook, he is survived by his wife, Carolyn Oldenbusch Kanovitz, and two grandsons.

Person TypeIndividual