Image Not Available

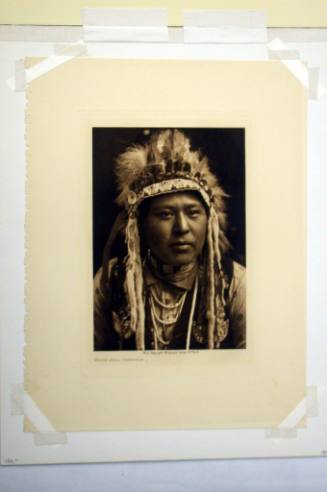

for Grace Carpenter Hudson

Grace Carpenter Hudson

American, 1865 - 1937

Raised in Potter Valley, near Ukiah, California, Grace Hudson became an acclaimed painters of Native American subjects, especially the Pomo Indians, independent tribes of coastal and inland Northern California. She left over 684 oil paintings and numerous pieces in other media including weavings, hooked rugs, and monochromatic sketches. The Grace Hudson Museum in Ukiah has the largest body of her remaining work.

As a child, she migrated with her family including a twin sister from Kansas Territory in 1857 and settled first in Grass Valley, California, and in 1860, they moved to Potter Valley, among the only white settlers. The Pomo Indians had much suffering and early death, and she early developed a sympathy and concern for them.

Her mother was also one of the first schoolteachers among the tribes and collected their baskets because of her respect for their workmanship. Her father had a business as journalist and photographer, and from him, she learned about the effects of light and composition.

Grace began art studies at age thirteen at the San Francisco Art Institute and later studied at the California School of Design with Virgil Williams and Raymond Yelland. From Williams, she learned classical techniques of drawing and modelling from plaster casts in classical motif for sculpture. The landscape class with Yelland was distinctive because it was held at the only art school in the country where pupils went into the outdoors directly to paint with their teachers.

Hudson got a reputation for working very rapidly and skillfully in her classes, and by age sixteen, won the Alvord Gold Medal, presented by the President of the San Francisco Art Association for the best full-length study in crayon.

In 1884, at age nineteen, she eloped with William Davis, a man fifteen years older. Her parents were extremely upset, and the marriage ended a year later. She returned to Ukiah to paint, teach and illustrate for magazines including Sunset and Cosmopolitan, and Overland Monthly, and her work from that time period carries the signature "Grace Carpenter Davis." She opened her studio to the public and exhibited her work which had no particular focus and included genre, landscapes, portraits and still lifes in all media.

In 1890 with her parents' blessing, she married John Wilz Napier Hudson, a physician for the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad Company who gave up practice to research the Pomo Indians and follow his deep interests in archeology and ethnography. They shared a sense that the Indians were a vanishing race and should be portrayed with sensitivity and respect for their culture.

In 1891 a visit to her studio by H. Jay Smith opened the door for her recognition far beyond her own region when he ordered work by her for the Minneapolis Art Association exhibit where it got much attention. A year later, a painting Little Mendocino, got much attention at the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco, and the following year it was hung at the World's Fair in Chicago. There she received a diploma for honorable mention on the work. From that time, her reputation was established, and she meticulously photographed and documented her oil paintings for posterity, one of the reasons being for copyright purposes because other artists tried to copy her popular work.

By 1900, her national reputation was secure, but she was exhausted, and she spent three months alone in Hawaii and then rejoined her husband, who had been named Assistant Ethnographer of the Field Columbian Museum. She traveled widely with him and documented many other Indian tribes including the Pawnee in Oklahoma Territory. Sadly many of her paintings and their extensive collection of Indian artifacts left behind in California were destroyed by the earthquake and fire of 1906.

In 1912, they moved into a Hopi style house in Ukiah and, with the exception of a trip to Europe in 1925, lived the rest of their lives there, active in the cultural life around them. She had a unique studio with an elaborate system of moveable skylights which she manipulated from skills learned from her father. She painted from Indian models who came to her studio.

Her husband died in 1936, and she died a year later on March 23, just after her seventy-second birthday. They had no children and left their possessions to a nephew, Mark Carpenter who made their home with over 30,000 objects a museum that has expanded into a lasting public memorial to his unique aunt and uncle.

Person TypeIndividual