Ludovico Carracci

Born Bologna, bapt 19 April 1555; died Bologna, 13 or 14 Nov 1619.

Painter, draughtsman and etcher. His father, Vincenzo Carracci, was a butcher, whose profession may be alluded to in Ludovico’s nickname ‘il Bue’ (It.: ‘the Ox’), though this might also be a reference to the artist’s own slowness. Ludovico’s style was less classical than that of his younger cousins Agostino and Annibale, perhaps because of a mystical turn of mind that gave his figures a sense of other-worldliness. Like his cousins, he espoused the direct study of nature, especially through figure drawing, and was inspired by the paintings of Correggio and the Venetians. However, there survives in his work, more than in that of his cousins, a residue of the Mannerist style that had dominated Bolognese painting for most of the mid-16th century. Ludovico maintained a balance between this Mannerist matrix, his innate religious piety and the naturalism of the work of his cousins. With the exception of some travels during his training and a brief visit to Rome in 1602, Ludovico’s career was spent almost entirely in Bologna. In the first two decades of the 17th century he lost touch with the activities of his more up-to-date Bolognese compatriots—contemporaries and pupils alike—who were then active in Rome, including his cousin Annibale. Ludovico’s later work became overblown and eccentric. This curious ‘gigantism’ was first evidenced in paintings of the late 1590s, but the tendency seems to have been reinforced by the monumental classicism of Annibale’s ceiling of the Galleria Farnese in the Palazzo Farnese, Rome, which Ludovico saw on his visit in 1602. In spite of his isolation in Bologna, Ludovico strongly influenced the subsequent development of painting in his native city and elsewhere, especially through his pupils, who included Guido Reni, Giacomo Cavedone, Francesco Albani, Domenichino and Alessandro Algardi.

1. Life and work.

(i) Training and early work, before c. 1590.

Probably sometime after 1567 Ludovico trained in Bologna with the Mannerist painter Prospero Fontana, though the precise date of his apprenticeship is unknown: to judge from his few surviving early pictures, he carried over little or nothing of Fontana’s style into his subsequent work. On 23 March 1578 Ludovico requested admission as master to the Corporazione dei Pittori in Bologna. According to Malvasia, at about this period he travelled to Florence, Parma, Venice and Mantua. On 28 June 1582 Ludovico was elected a member of the council of the Compagnia dei Bombasari e Pittori, Bologna.

The earliest known paintings by Ludovico were made shortly after c. 1580; they reveal the influence of Federico Barocci, though they also hark back to an earlier tradition of Emilian painting, most notably to the work of Niccolò dell’Abate. Examples include the Mystic Marriage of St Catherine (c. 1581–2; Bologna, priv. col., see 1993–4 exh. cat., no. 1) and the St Vincent Martyr (c. 1580–83; Bologna, Credito Romagnolo). In composition and handling, the St Vincent is indebted to both Correggio and Barocci, the latter’s print of the Virgin and Child (b. 2) providing the model, in reverse, for Ludovico’s figure group in the upper right of the picture. Also datable from the first half of the 1580s are the Sacrifice of Isaac (Rome, Pin. Vaticana), though it is often dated rather later, and the Mystic Marriage of St Catherine, with SS Francis and Joseph and Two Angels (Göteborg, Kstmus.). The best-known work from the first half of the 1580s—and the one that shows Ludovico’s early style at its most elegant and attractive—is the Annunciation (1583–4; Bologna, Pin. N.), which was commissioned by Giulio Cesare Guerini for the room of the Compagnia del Santissimo Sacramento, adjacent to the former church of S Giorgio in Poggiale, Bologna. The colours, form and sentiment are still Baroccesque, though there is now a stronger element of Correggio’s presence. Yet in spite of these influences, the idiom is also now clearly Carraccesque in form and style. In 1584, together with Agostino and Annibale, Ludovico completed for Filippo Fava the fresco cycle of the Stories of Jason on the frieze of the Gran Salone in the Palazzo Fava, Bologna. Ludovico’s share may be only surmised from stylistic evidence: it is now widely agreed that he was responsible for much of the Enchantment of Medea and the Rejuvenation of Aeson.

Some two years earlier, also together with his two cousins, Ludovico had founded the Accademia dei Desiderosi (the so-called Carracci Academy), of which he was nominated head. The three artists treated the academy as yet another of their collaborative enterprises, and it enabled them to explore their artistic reforms with greater independence. The academy was also a channel through which commissions flowed from the city’s churches and the local nobility, commissions that were then diverted by Ludovico to whichever of the three artists were available or most suited to execute the project.

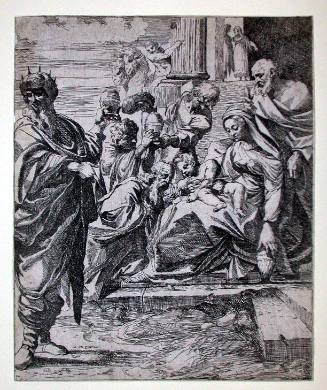

In the second half of the 1580s Ludovico began to receive commissions from leading Bolognese families for altarpieces in important local churches, among them S Francesco, where the Conversion of St Paul (1587–8; Bologna, Pin. N.) was painted for the family chapel of Emilio Zambeccari. Another example is the Madonna and Child Adored by Saints and Donor (1588; Bologna, Pin. N.), painted for the Bargellini family, who installed it in the Buoncompagni Chapel of the church of the Monache Convertite in Via Lame (now S Maria del Buon Pastore). Signed and dated lvd. Caratius f. mdlxxxviii, the Bargellini Madonna is Ludovico’s first signed painting; it marks his full maturity as a painter and it is also one of his most successful works. The majestic composition, clearly inspired by the airy altarpieces of the great Venetians, such as Titian and Veronese, represents a new departure in his style. The graceful movement and gentle humanity of expression attained in his figures became a hallmark of his style during this and the following decade. Also probably painted in the mid- to late 1580s (though sometimes dated early in the next decade) is another celebrated altarpiece, the Immaculate Virgin Adored by Saints (the ‘Madonna degli Scalzi’; Bologna, Pin. N.), which was painted for the Bentivoglio Chapel in the church of the Madonna degli Scalzi in Strada Maggiore.

In the early part of his career, Ludovico also specialized in two other categories of painting: portraits and small-scale works on copper, painted either as devotional pieces or cabinet pictures. Highly finished, the latter are exquisite in handling and iridescent in colour. The jewel-like appearance of the Marriage of the Virgin (1588; London, priv. col., on loan to N.G.) is also a consequence of the elegant poses of the figures and the complexity of the whole composition. Such pictures later exerted a strong influence on the young Centese painter Guercino.

Ludovico was also successful as a portraitist, capturing a likeness as well as conveying something of the personality and mood of the sitter. The well-known portrait of the Tacconi Family (c. 1588–90; Bologna, Pin. N.) is among his best works of the type. Malvasia mentioned it when it belonged to the Bonfiglioli family, pointing out that Prudenza Tacconi was Ludovico Carracci’s sister; she is shown alongside her husband Francesco and their two children Gasparo Gilippo and Innocenzo, who was later to become a painter. In the second part of his career, Ludovico seems to have more or less given up portraiture; at least few or no independent painted portraits have survived.

(ii) Middle years, c. 1590–1601.

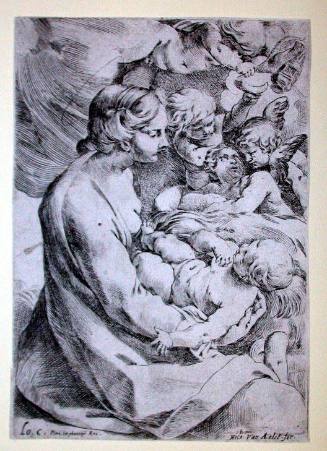

The 1590s mark yet another step in Ludovico’s development. As if he had already determined to stay in his native city for good, the painter declined an invitation to enter into the service of the Farnese family in Rome, an offer subsequently taken up in 1595 by both Agostino and Annibale. Ludovico’s work of the 1590s is characterized by a more sombre palette, suggesting that the early influence of Barocci had finally been supplanted by that of the Venetians: rich earth colours, with the occasional dark blue, green and purple, are bathed in a more broken, uneven light. Typical of this new painterly direction is the Holy Family with St Francis and Donors (1591; Cento, Pin. Civ.), which was commissioned by Giuseppe Piombini of Cento for the altar of his family chapel in the church of the Cappuccini at Cento. The patron is depicted as St Joseph, while members of his family, Pietro Antonio Piombini and his wife, Elisabetta Dondini, appear in contemporary dress at the lower right of the picture. The exciting potential of this great altarpiece was recognized some 25 years later by the young Guercino, who acknowledged its strong impact on him by the nickname he gave it, ‘La cara cinna’ (or ‘Dear mother’s breast’), referring to the nourishment it had provided in his tender years. These same qualities are more strikingly present in another altarpiece, the Martyrdom of St Ursula (1592; Bologna, Pin. N.), formerly placed in the church of S Girolamo, Bologna; it is similarly Venetian in feel and, perhaps more than any other of Ludovico’s pictures, owes the greatest debt to the work of Veronese.

The daylight ambience that Ludovico favoured in his altarpieces of the 1580s was increasingly replaced in his work of the succeeding decade by more dramatically lit nocturnes. Accompanying this darkening of the palette and pictorial setting was an intensification of the emotional states of the participating figures, features seen in a number of other altarpieces made for Bolognese churches at this time: the St Hyacinth (1594; Paris, Louvre), painted for the Turrini Chapel in S Domenico; the Transfiguration (c. 1595–6; Bologna, Pin. N.), commissioned by Dionigio Ratta for S Pietro Martire; and the Probatica piscina (1595–6; Bologna, Pin. N.), commissioned by Giovanni Torfanini for the then new church of S Giorgio in Poggiale.

Ludovico’s collaboration with his two cousins on decorative fresco cycles in the palazzi of wealthy Bolognese patrons also continued into the mid-1590s. They worked together on the decoration of the Palazzo Magnani–Salem; the date 1592 is inscribed on the fireplace of the Gran Salone, which contains frescoes with Stories of the Founding of Rome. The extent of Ludovico’s share of the decoration, probably begun c. 1589, remains controversial: it seems to include the She-wolf, though the preparatory drawing for this (Paris, Louvre) is unquestionably by Annibale, the Rape of the Sabines and the Sabine Women Intervening in the Battle between the Romans and the Sabines, though, again, the related preparatory drawing (Chatsworth, Derbys) is by Annibale. In 1592 Ludovico and Annibale were commissioned to decorate two chimney-breasts in the Palazzo Lucchini, for which Ludovico painted Alexander and Thais Setting Fire to Persepolis (detached fresco now Bologna, Pal. Francia). In 1593–4 he helped decorate a number of rooms in the Palazzo Sampieri–Talon.

Towards the end of the decade, Ludovico began to make his figures colossal in size, one of the first examples of this ‘gigantism’ being the Ascension, painted for the high altar of the church of S Cristina, Bologna (1597; in situ). By the end of the 1590s Ludovico’s position as Bologna’s pre-eminent painter had been earned by the consistently high quality and originality of his pictures. He painted another version of the Martyrdom of St Ursula (?1600; Imola, S Domenico) and the Birth of the Baptist (Bologna, Pin. N.), which was commissioned in 1600 by Dionigio Ratta for the high altar of the church of S Giovanni Battista, Bologna, but apparently erected only in 1604. This was also the time when younger rivals appeared on the scene and began to establish themselves at Ludovico’s expense. In 1598 Guido Reni was chosen in preference to both Ludovico and Bartolomeo Cesi to decorate the apparati (temporary structures) erected in Bologna in honour of Pope Clement VIII, and he nearly supplanted Ludovico in the commission from Ratta for S Giovanni Battista. According to Malvasia, Reni offered to paint this altarpiece for half the price that Ludovico was asking and even presented the patron with a beautiful drawing showing a preliminary idea for the composition (possibly Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Lib., 2328).

(iii) Late work, 1602 and after.

Ludovico’s visit to Rome, documented as having taken place between 31 May and 13 June 1602, gave him the opportunity to see at first hand the new, classicizing style that his cousin Annibale had evolved in his decorations of the Palazzo Farnese. Malvasia, who all too frequently championed Ludovico’s interests at the expense of those of his cousins in his lives of the three painters, claimed, rather improbably, that a motive for Ludovico’s visit was to ‘raggiustare la galleria Farnese’ (to retouch or correct the frescoes in the gallery), a statement made all the more implausible by the fact that the ceiling had been unveiled the previous year. Nevertheless, Ludovico’s Roman journey did seem to mark a milestone in his career: from then on the ‘visionary’ or ‘neo-Gothic’ element in his style became more pronounced, becoming the hallmark of his last phase.

On 18 January 1603 the funeral celebrations in honour of Agostino Carracci that Ludovico had organized, together with other members of the Carracci Academy, took place in Bologna. A pamphlet entitled Il funerale d’Agostino Carraccio fatto in Bologna sua patria, with engravings by Francesco Brizio and Guido Reni, said to have been based on drawings by Ludovico, was published soon after by Benedetto Morelli. In the spring of the same year Monsignor Giovanni Battista Agucchi put forward Ludovico’s name to the Fabbriceria of St Peter’s, Rome, as an artist ideally qualified to paint one of the altarpieces for the basilica. The recommendation proved abortive and the commissions were instead shared among the members of the Tusco-Roman faction of painters then active in Rome, such as Cristofano Roncalli, Giovanni Baglione, Bernardo Castello, Domenico Passignano and others.

The following spring Ludovico began one of the largest decorative undertakings of his late period, the fresco cycle of the Story of St Benedict in the octagonal cloister of the convent of S Michele in Bosco, Bologna. The commission, which Ludovico seems to have begun planning as early as 1602–3, was completed in April 1605, together with members of the by then renamed Accademia degli Incamminati, mostly members of his workshop. The cycle is now a ruin, with only the odd passage of original paintwork surviving. The 37 frescoes of which it is composed are subdivided by caryatids and are contained within an elaborate architecture. Ludovico painted seven of the scenes; the remainder was divided between his pupils and associates. Although the subject-matter is religious, the conception of the whole has been seen as a response on the part of Ludovico to Annibale Carracci’s secular compositions on the ceiling of the Galleria Farnese.

Ludovico was next engaged by Bishop Claudio Rangoni on the decoration of the choir of Piacenza Cathedral, with Stories from the Life of the Virgin, a commission on which he worked together with Camillo Procaccini. The only surviving payment to the artist is dated 11 June 1605, but work continued until 1608, when the decoration was unveiled. Ludovico’s share comprised some of the large-scale canvases that formerly decorated the walls of the choir, including the massive Funeral of the Virgin and the Apostles at the Tomb of the Virgin (both Parma, G.N.), which were removed c. 1800 when the interior of the cathedral was ‘restored’. Still in situ are his frescoes of the Glory of the Heavens occupying three of the four spaces of the vault (the fourth, the Assumption of the Virgin, was painted by Procaccini). Ludovico’s contribution is memorable for the colossal scale of the figures, whose exaggerated proportions mark the culmination of the process begun a decade earlier.

During the last ten years of his life, Ludovico was increasingly eclipsed by younger rivals, most notably by Guido Reni who returned from Rome in 1613 to take up work on two prestigious commissions, the decoration of the apse of the chapel of S Domenico in the church of S Domenico, Bologna, and the high altar of the church of the Mendicanti. In contrast to the suave modernity and brightness of colour of Guido’s mature work, the paintings of Ludovico’s declining years seem drab and remote. Nevertheless, the best of them have an eccentricity and mystical power, the like of which was only to reappear in English history painting of the late 18th century, in the work of such painters as James Barry and Fuseli.

Ludovico’s late pictures include the Calling of St Matthew (probably c. 1606–7; Bologna, Pin. N.), painted for the chapel of the Compagnia dei Salaroli, S Maria della Pietà, Bologna; the Crucifixion (c. 1610–13; Ferrara, S Francesca Romana); the Preaching of St Antony (c. 1614–15; Milan, Brera), done originally for the high altar of S Antonio Abate, the Collegio Montalto; the Martyrdom of St Margaret (1616) for the Gonzaga Chapel of the Theatine church of SS Maurizio and Margherita, Mantua (in situ); and the justifiably famous Paradiso (1617; S Paolo Maggiore, Bologna).

2. Working methods and technique.

Ludovico’s working method combined long-standing, traditional procedures of painting and drawing with a new attitude towards pictorial conception that he and his cousins introduced into their work in the 1580s. The basic practices of preparing pigments and other materials, making detailed preliminary studies on paper for a given work, enlarging and transferring compositions from one surface to another, making cartoons, painting from scaffolding (in the case of large-scale wall and ceiling decorations) and so on were, in essence, those that had been employed and perfected in painters’ workshops in Italy during the preceding hundred years or more, though, doubtless, with a few ‘house’ variations, as there would have been in any other painter’s studio or workshop of the period.

The well-known Carracci reform of painting, in which Ludovico played his part, was therefore not so much a revolution in the use of materials or particular practical methods but in the presentation of pictorial subject-matter. Annibale was the first to realize fully a more lucid, naturalistic conception of a given composition and to give form to this idealized view of the world in his mature work; he was followed at the outset of his quest by both Agostino and Ludovico. The Carracci’s pursuit of a more naturalistic conception of the subject gave drawing an important role, enabling them to confront nature and to obtain a more truthful rendering of reality. Ludovico’s drawings of the 1580s and 1590s, together with those of his cousins from the same period, show this striving towards a more naturalistic rendering of the human figure.

More personal to Ludovico was his method of preparing a composition by means of a series of preparatory drawings that differ widely in design, even though they were all conceived for the same work. He seems to have considered many possible solutions for a given composition before finally opting for one. Sometimes no strong formal development seems to link together a sequence of drawings for a given composition. Yet for such a seemingly erratic creative process, Ludovico had a distinguished Emilian forerunner in Parmigianino, whose preparatory drawings for pictures reveal a similar richness of invention; and it can be no accident that Ludovico’s compositions are sometimes strongly redolent of those of Parmigianino. Another trick of Ludovico’s drawing technique finds an echo in his finished painting. This was his adoption of a paper cut-out correction, which was laid down on to the compositional study, usually to alter the position of a figure. Such a correction was used for the kneeling figure of the saint in a preparatory drawing (Paris, Louvre) for the altarpiece of St Carlo Borromeo Adoring the Virgin and Child (Forlì, Pin. Civ.). The consequent silhouetting effect is often carried over into the pictures; it is, for example, especially marked in the Ascension (Bologna, S Cristina), where the background figures do indeed look like cut-outs silhouetted against the sky.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Ludovico’s considerable influence on the evolution of 17th-century Bolognese painting was due to a number of factors, including his long-held position as head of the Carracci Academy. He seemed to regard his tenure of this office as a personal calling and, in spite of pressing invitations on the part of influential patrons to work outside the city, he was not prepared to relinquish it. He was also undoubtedly effective as a teacher and organizer, a quality well exemplified in the decoration of the cloister of S Michele in Bosco, which brought together many of his pupils and associates from the academy. Moreover, his ability as a teacher and communicator enabled him to pass on to a succeeding generation of painters the essential lessons of the Carracci reforms. This ensured that his compositional vocabulary, his penchant for sombre colours and dramatic lighting and, indeed, his personal brand of religious devotion were echoed throughout the century and beyond. The impact of his art was therefore felt by Bolognese painters as diverse as Guercino and Giovanni Andrea Donducci, called Mastelletta, at the beginning of the 17th century, and Domenico Maria Canuti and Giuseppe Maria Crespi at the end.

Although highly regarded in England in the 18th century by such critics as Joshua Reynolds, Ludovico’s work fell out of fashion in the 19th century, along with that of his cousins and, indeed, the whole of the rest of the Bolognese school of painting of the 17th century and the early 18th. Interest in Ludovico’s work was rekindled just before the middle of the 20th century, along with the general revival of interest in the Carracci. A milestone in this process was the monograph on the painter published in 1939 by the German art historian Heinrich Bodmer. Thereafter Ludovico’s work began to receive the re-evaluation that it deserved, though interest in his work has tended to lag behind that of his more famous cousin Annibale. The process of reassessment has continued, as exemplified by the monographic exhibition held in Bologna and Fort Worth, TX, in 1993–4. Nevertheless, this process is far from complete: problems of chronology and the attribution of several paintings remain, while the considerable task of gauging his work as a draughtsman requires further attention.

C. van Tuyll van Serooskerken, et al. "Carracci." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T014340pg1 (accessed April 10, 2012).