Reed Estabrook

Mr. Estabrook Goes to Washington - by David Buuck

Imagine an artwork that, no matter how many times it is copied and reproduced, always retains its economic value and, with millions of copies in circulation, can no longer be said to have an original. You can buy copies, but you can't make your own copies. Now imagine this artwork contains within it images of public institutions and ideals, institutions and ideals that the artwork itself tends to corrupt, yet which are nonetheless relied on for the legitimacy and insurance of the artwork's economic value. Photography? Cinema? No, a mechanically reproduced art form that historically precedes both of these modern reproductive technologies: money. Money, that strange commodity that can be made to stand in for almost anything and yet also can only refer to itself as substantiation of its worth. The abstract art par excellence, the meaning of which is that which it declares, if only to the extent that we collectively put our faith in that declaration.

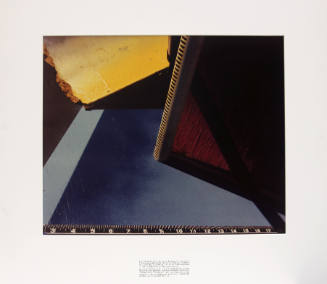

Reed Estabrook, an Oakland-based photographer and professor of art at San Jose State University, has begun an investigation of the aesthetics of money, one that arcs from the institutional images on U.S. bills to the actual institutions themselves. In God We Trust is a series of photographs, taken of sculptural works in clay. Each sculpture bears an imprinted image of one of the governmental buildings pictured on each of the twelve bills currently in circulation. The clay reliefs are at once fragile and cracked (meant to symbolize the "broken system" of campaign financing), while seemingly rigid and ancient, reflecting both the neoclassical architecture used on most federal buildings and the ancient Greek and Roman systems of democracy to which such neoclassicism refers. The photos themselves, bathed in a sepulchral wash of shadow and light, represent an ethereal meditation on politics and representation.

The In God We Trust series is not a total departure for Estabrook. His earlier works involved similar mediations between architecture, sculptural modeling, and photography. A photo of a building or site becomes the model for a photograph, which in turn becomes a model for a sculpture, itself a model for the "final" photograph. Though primarily a photographer, Estabrook finds that the photo itself is "never enough." The layering of reproduction and simulacrum in his work not only explores the thin line between art and reality, but it also challenges the documentary presumptions of photography itself.

In this new project, Estabrook's models were, in his words, "already in my pocket." Dollar bills, themselves mechanically reproduced copies of a rather abstract "model" (that of exchange value), became for him the starting point of a series of transfers and reproductions. The architectural recreations on currency, themselves idealized framings of highly symbolic sites/seats of power, lead the artist to the buildings themselves, which in turn become rearticulated in sculpted and cracked clay. These sculptural reliefs are then the models for the final photographs, which, like money itself, can be endlessly reproduced.

In Gifting Congress, an extension of this series, Estabrook put these images back into the public realm of governmental politics, mailing prints of his photos to members of congress with a plea to reform the campaign finance system. In this action he took his $300 tax rebate from last year and "reinvested" it in the political economy. Here, then, photography becomes but one element of a much broader conceptual art projectópart political prank, part mail art, and part collaborative performance art (as legislators write back to Estabrook).

In February of this year, Estabrook sent his prints, along with a letter and artist's statement, to each member of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. In the textual portion of the package, he detailed the context for the photographic "gift," including specific mention of the Shays-Meehan campaign finance reform bill then under (re)consideration by Congress. The connection between the prints and campaign finance reform is that, as Estabrook argues in his letter, "the principal instrument of corruption and undue influence, the 'greenback,' bears upon it the images of those same institutions that it subverts." Ironically (and perhaps tellingly), due to the post-9/11 anthrax scare, almost all of Estabrook's packages were held up in the U.S. Postal Service, while the privately owned carriers such as UPS and FedEx continued to have direct access to the government.

Gifting Congress, in its open-ended form, holds out the possibility for "audience response," either in action or reaction. Indeed, Estabrook has begun to receive notes and letters from some of the recipients of his packages (several of which will likely end up on his website documentation of the project, at http://ReedEstabrook.net/return.html). Many of these letters appear to be standard form replies, likely processed by staffers; a few, however, are handwritten notes making special reference to both Estabrook's "donation" and the issue of campaign finance reform. Heather Wilson, the Republican congresswoman from New Mexico, scribbled off a barely legible card that could perhaps be read as some strange mix of official document and extended political haiku:

Dear Reed, Thanks for the photograph. You & I probably do not agree on campaign finance and the first amendment, but I appreciate the art.

Regards, Heather

While a typed transcription cannot do justice here to the semiotic richness of the card itself, the ironies shine through nonetheless (here it's the artist who's somehow against "free" speech, not the congresswoman). Indeed, the ongoing wealth of "official" response to Estabrook's gifts not only extends the temporal frame of the project, but to some degree puts the completion of the art in the (unwitting, no doubt) hands of that hydra-headed beast we want to imagine as the people's government. Completion in this sense, of course, does not necessarily translate into specific legislative action; it could just as easily become what Estabrook terms the "residual detritus" of citizen appeals, official campaign donations, and staffer booty. That one cannot know, much less control, the reception of such work is only further testament to the democratic impulses of this project, stretching far beyond the familiar art world context and into that most privileged and rarified of public spheres.

While Citizen Estabrook is not taking any credit for the eventual passage of campaign finance reform legislation earlier this year (he gives that credit to the Enron scandal), his artistic intervention into the realm of politics is a subtle twist on the old adage "nothing talks louder in politics than money."

http://www.reedestabrook.net/index.html