Garry Winogrand

Nationality: American. Born: New York City in 1928. Education: Studied painting at City College of New York, 1947-48; Columbia University, New York, 1948-51; studied photography, under Alexey Brodovitch, New School for Social Research, New York, 1951. Military Service: Served in the United States Air Force, 1945-47. Family: Married the dancer Adrienne Lubow in 1952 (divorced); children: Lauri and Ethan; married Eileen Winogrand; daughter: Melissa. Career: Freelance photographer (initially a commercial photographer, working with the Pix agency, then Brackman Associates), New York and Los Angeles, from 1952. Teacher from 1969: taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago; Instructor of Photography, University of Texas at Austin, 1973. Recipient: Guggenheim Fellowship, 1964, 1969, 1978; New York Council on the Arts Award, 1971; National Endowment for the Arts grant, 1975. Agent: Pace/MacGill Gallery, 32 East 57th Street, New York 10022, USA. Died: (in Tijuana, Mexico) 19 March 1984.

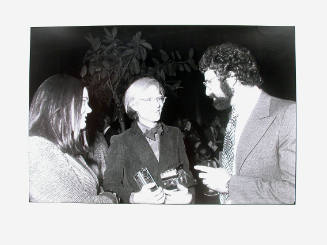

Garry Winogrand was perhaps the epitome of the modern street photographer, the mode many regard as photography at its basic best. One of the finest virtuosos of the 35mm camera after Cartier-Bresson, he was a fast talking, fast shooting New Yorker, who took the lively, unschooled ``snapshot aesthetic'' and elevated it into a sophisticated game--or art--of fast reflexes, chance, intuition, and insight. In the course of his career he exposed well over two million frames, training his Leica at anything and everything--but chiefly the manners and mores of his fellow Americans, discreetly catching them on the wing in the city streets, stealthily capturing every nuance of their social gatherings.

``I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs'' was his favourite maxim, which suggests he was a formalist. He was a leading light of the so-called ``social landscape school'' of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, a loose grouping of photographers who aimed their cameras at the social landscape of America but who were more concerned with the language of the photographic medium, nominally documentary realists who were in effect mirroring their own, somewhat malcontent soul rather than the society which surrounded them.

Intent and effect in photography are frequently two different things, for the real world constantly frustrates those with purely formalist or self-referential motives. However subjective, indulgent or historical Winogrand's view, it remains a view of society. Winogrand's world view, after all, was New York Jewish, and what could be more worldly than that?

His pictures, particularly of those gatherings to which one might append a socio-political ``spin,'' reflect all the scepticism and alienation of the common New York mensch, particularly one whose views were born out of the dark days of Eisenhower and the Cold War. They are often humorous, usually cruelly humorous, with sharp, pungent punchlines that reflect very much the crackle of street conversation. There is little sentimentality in Winogrand and a lot of casual cynicism, only occasionally leavened by a streak of schmaltz, which he seemed to reserve mainly for animals.

In searching for what he had not seen before, Winogrand extended profoundly our notions of the formal potential of photography, and through the agency of these new forms extracted new meanings from the world. The nature of these meanings--fragmentary, elliptical, intensely personalised--do not make for comfortable viewing. We are disturbed by the hardness of Winogrand's mind even as we cherish his keen eye. We must continually ask whether sour misanthropy wins out over existential despair, finely judged satire over self-indulgent irony.

Garry Winogrand--by his own admission psychologically scarred yet at the same time liberated by such events as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Kennedy assassination--seems the bleakest of the social landscapists, his lack of belief in the ``truth'' of photography the most complete. Nevertheless, the vast gallery of characters photographed by Winogrand seems to tell a particular, if jaundiced truth about a particular era in America--an era of brief hope followed by disillusion; of surface glitter delivering empty promises. Winogrand was one of the great photographic existentialists, as adrift as Robert Frank in an America with which he could not quite connect; the wandering Jew lost in the boundlessness of America and the convoluted yet wholly original meanderings of his work.

Retrieved from "Garry Winogrand." Contemporary Photographers. Gale, 1996. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 21 Feb. 2012.

http://ic.galegroup.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?displayGroupName=Reference&disableHighlighting=false&prodId=BIC1&action=e&windowstate=normal&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK1653000707&mode=view&userGroupName=tall85761&jsid=26a7d9a74cc2ee9da10cc18751d36e01 (Accessed Feb. 21, 2012)