Winslow Homer

American, 1836 - 1910

Winslow Homer was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1836, the second of three sons of Henrietta Benson and Charles Savage Homer. His father, a hardware importer, and his mother, an amateur watercolorist, encouraged his early interest in art. Given that no art schools and no art institutions existed in the Boston area during Homer's youth, he, like many of his contemporaries, had to piece together his own artistic training. He began by working for the commercial lithographer John H. Bufford, an acquaintance of his father. In 1857, after two years as an apprentice to Bufford, Homer left the firm, rented a studio in the Ballou Publishing House in Boston, and launched his career as a freelance illustrator. He initially worked for Ballou's Pictorial and Harper's Weekly among other weekly magazines, and later illustrated various literary texts by celebrated authors, including the poets William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alfred Lord Tennyson.

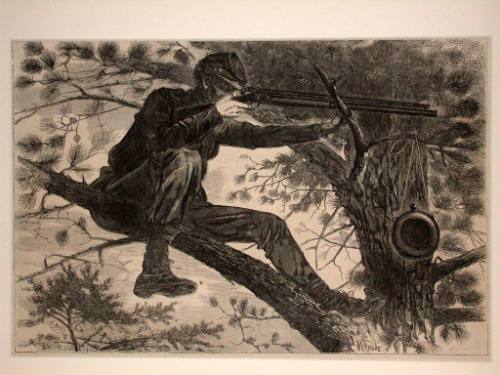

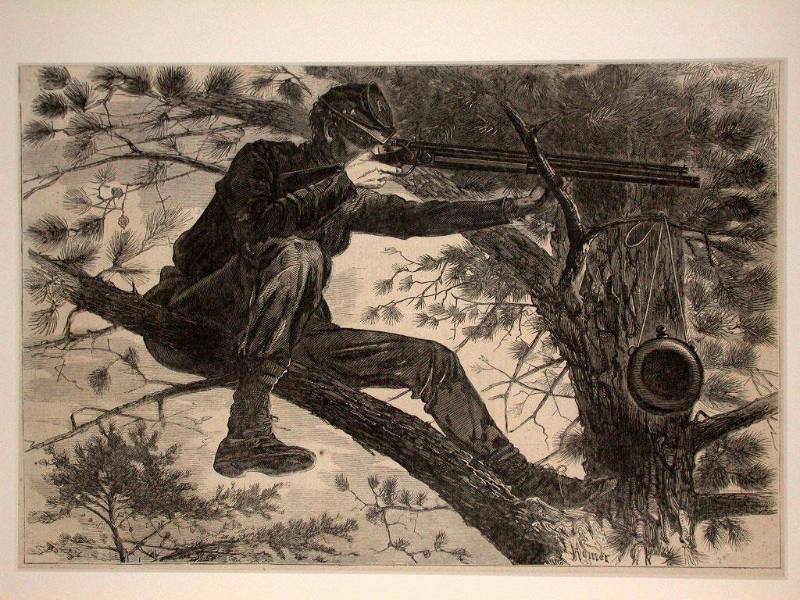

In 1859, Homer moved to New York, where he continued to freelance for Harper's Weekly and other publications while establishing his reputation as a painter. Shortly after his arrival, he decided to further his artistic training: he enrolled in life drawing classes at the National Academy of Design and took a month of painting lessons from the French genre and landscape painter Frédéric Rondel (1826-1892). During the Civil War, he served as an artist-correspondent for Harper's Weekly, visiting the front several times and illustrating the daily routine of camp life on the Union side. His wartime experiences inspired numerous oil paintings, and critical acclaim for this work led to his 1865 election to the National Academy of Design as a full academician.

Following the great success of his Civil War images, Homer took his first trip to Europe in December 1866. He spent ten months in France, sharing a studio in the Montmartre district of Paris with a friend from Massachusetts, Albert Warren Kelsey, and briefly visiting the countryside. During his stay abroad, he did not enroll in any art classes but worked on his own, completing nineteen small oil paintings and three illustrations for Harper's Weekly. His works from this period display the influence not of contemporary, avant-garde French painters, such as Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet, but of older, more traditional Barbizon School artists and Jean-François Millet.

After returning from France, Homer continued to work as a painter in New York and resumed his practice of painting in series, concentrating on depictions of women and children in outdoor settings. Despite his past triumphs, the new pictures received mixed reviews and sold for only modest prices. In the early 1870s, he began pushing his art and artistic practice in new directions. Most likely in response to a very successful exhibition of American and European watercolors at the National Academy of Design in February 1873, Homer first explored watercolor as a distinct means of artistic expression during a trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts, in the summer of 1873. He exhibited the works completed during this Gloucester visit at the American Society of Painters in Watercolors in the spring of 1874 and became a member of that organization three years later.

In addition to adopting watercolor as a primary form of expression, Homer altered his approach to art: he found inspiration in Japanese art, incorporating subtleties of design, such as asymmetrical pictorial arrangement and flat areas of color, into his work, and he embraced the Aesthetic Movement's emphasis on beauty rather than meaning in a series of pictures portraying genteel, fashionably dressed women. These shifts in style and subject matter were accompanied by a new interest in decoration-Homer made two sets of tiles for fireplaces and became an active member of the Tile Club, decorating tiles at the meetings of this New York artists' group.

In 1881, Homer traveled to England and settled in Cullercoats, a fishing village and artists' colony near Newcastle, for almost two years. This experience had a profound effect on his art and life, and he undertook the subject of the human struggle with nature that would occupy him for the rest of his career. Working primarily in watercolor, he made numerous pictures of the local inhabitants, particularly the fisherwomen. Departing from his prior depictions of leisure class women and farm girls, he represented the women of Cullercoats in a monumental, heroic manner that conveyed a sense of strength and courage. In doing so, he changed his watercolor painting technique, both enlarging the size of his compositions and carefully planning them in his studio, often using preliminary studies.

In November 1882, Homer returned to New York City, but, a little more than a year later, frustrated by his financial situation, he retreated to Prout's Neck, Maine, not far from Portland. He lived, mostly alone, on this rocky promontory, and built a studio overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. In this new setting, Homer's subject matter shifted away from women and children to the sea, the wilderness, and the men who frequented such places. Many of his images involve references to the physical and spiritual power of nature-storm winds gusting, sunlight reflecting off the sea-and/or to mortality-hunters carrying their catch, fishermen answering calls of distress. In the mid-1880s, while painting his sea pictures, Homer made his first etchings. He etched eight plates between 1884 and 1889, seven of which were based on his sea paintings and his English watercolors.

Although Homer isolated himself in Maine, he continued to travel, sometimes accompanied by his father, to a wide variety of locales, including the Adirondacks, Canada, Bermuda, Florida, the Bahamas, and Cuba. Watercolor, portable and quick drying, became Homer's preferred medium during these working vacations, and much of his later fame rests on these quickly rendered, impressionistic paintings. In 1890, Homer created the first in a series of pure seascapes at Prout's Neck. These works, with their bold, dramatic portrayal of waves crashing against the rocky shore, became the most admired of his late oils.

The recipient of numerous awards and honors during his lifetime, Homer was widely regarded as one of the most important painters in the United States by the final decades of his career. Admiration for Homer's work remains undiminished since his death in 1910, and his position in the top echelon of nineteenth-century American artists is secure.

Winslow Homer is recognized as a dominant figure in nineteenth-century American art and his era's foremost exponent of realism. Based on direct observation, his works of the 1860s and 1870s reveal actualities of American life that went unrecorded by other artists. Homer's art from the 1880s through his death in 1910 dealt primarily with mortality and the forces of nature, conveying these essential themes in potent images in which light, shadow, and composition play powerful expressive roles. Today, Homer remains one of the most esteemed and cherished of American artists of all time.

Homer was born in Boston in a long-established New England family and grew up in nearby Cambridge, where he led an active outdoor life. Encouraged by his parents to pursue an artistic career, he became an apprentice in the Boston lithographic firm of J.H. Bufford at age nineteen. His only formal training consisted of a few drawing classes in Brooklyn, a brief period of study at the National Academy of Design, and a number of private classes with the painter Frederick Rondel in Boston. After three years of training at Bufford's, he left the firm to become a freelance illustrator. His drawings were readily accepted by Ballou's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion and later by Harper's Weekly, the best magazine of its time. In 1859, Homer moved to New York City, where he became a leading illustrator for Harper's.

During the Civil War, Harper's Weekly sent Homer to Virginia, where he drew a great number of scenes of the front. His sketches became the basis for some of his earliest oil paintings, including his famous Prisoners from the Front, (1866; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Featuring life in camps rather than battlefields, Homer's Civil War scenes are among the most powerful and authentic records of Union troop experience produced.

Homer began submitting paintings to the annual exhibitions of the National Academy of Design in 1863 and was elected a full Academician two years later. In 1866, he traveled to Europe, where he spent ten months in France. Although the details of his activities on this sojourn are scarce, it is known that he visited the Exposition Universelle to see his Prisoners from the Front, which was on display. At the time, he probably viewed the separate exhibition of works by Gustave Courbet, France's leading realist. He may also have been exposed to the bold, still-controversial art of Edouard Manet.

On his return to the United States, Homer settled in New York, where he lived for the next thirteen years. In 1872, he moved to the famous Tenth Street Studio Building, which was home to many Hudson River School artists and later to William Merritt Chase. During the 1870s, Homer explored a variety of subjects, including scenes of rural life and recreational activities as well as themes of childhood. His works were a reflection of both his own nationalistic concerns and the general post-war nostalgia for America's past. Unlike the anecdotal sentimentality found in the work of many of his contemporaries, such as J.G. Brown, Homer created genre paintings [such as the two versions of Snap the Whip, (1872; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio) that exemplify his lifelong penchant for realism coupled with an exacting and carefully observed portrayal of light and shadow.

During the late 1860s and 1870s, Homer painted in a number of different locales. He worked in upstate New York at Saratoga Springs, Lake George, and the Adirondack Mountains. In the summers of 1873 and 1880, he spent time in Gloucester, Massachusetts. It was during his 1873 stay in Gloucester that he first worked in watercolor. He would use the medium for the rest of his career, creating some of the finest watercolors produced in America during his era. In 1874, he exhibited for the first time at the American Society of Painters in Watercolor. Three years later, he became a member of the organization. In the mid-1870s, Homer visited Virginia, producing a number of images of former slaves. These works are viewed today as the American analogues of paintings depicting peasants by members of the French Barbizon School. During a stay in 1878 at Houghton Farm, the home of one of his patrons in Mountainville, New York, Homer created a number of his finest early watercolors.

Homer made a second trip to Europe in 1881. Unlike most of his fellow American artists, who flocked to Paris, Homer went to England, spending almost two years at Cullercoats, a small fishing village on the North Sea. In Cullercoats, Homer worked almost exclusively in watercolor, developing a broader, more fluid technique and using a darker palette. He also replaced his earlier native genre subjects with more serious themes concerning the local fishing-folk and their relationship with the sea. In key paintings such as Fog Warning, (1885; (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), rendered after his return to America, he explored the theme of man versus nature, which would emerge more fully in his later art. Revisionist art historians suggest that the English Tyne School as well as the work of Joseph Mallord Turner and John Constable were possible sources of influence on Homer's development during this period.

Homer returned to America in November of 1882. In 1884, a desire for solitude coupled with a generally reclusive nature, contributed to his decision to move to the isolated locale of Prout's Neck, Maine, which would remain his home for the rest of his life. Here he created his great series of views of the sea, which express the theme of mortality with the dramatic imagery of crashing waves against jagged rocks. Among his classic seascapes from this period are Cannon Rock, (1895; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Northeaster (1895; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). During this last period of his career, Homer also made frequent trips to warmer climes including Cuba, Nassau, Bermuda, and Florida in order to escape the harshness of Maine's winters. In watercolors created on these trips, he conveyed the brilliant light and vibrant colors of the tropics.

Winslow Homer died in Prout's Neck in 1910. His works may be found in important private and public collections across the country including: the Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts; Art Institute of Chicago; the Brooklyn Museum, New York; the Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio; Canajoharie Library and Art Gallery, New York; the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; the Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence; the Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts; the Musée D'Orsay, Paris; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the New Britain Museum of American Art, Connecticut; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.; the Saint Louis Art Museum; the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts; Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Massachusetts; the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

Person TypeIndividual