Annibale Carracci

Born Bologna, bapt 3 Nov 1560; died Rome, 15 July 1609.

Painter, draughtsman and printmaker, brother of (2) Agostino Carracci. Since his lifetime, he has been considered one of the greatest Italian painters of his age. His masterpiece, the ceiling (1597-1601) of the Galleria Farnese, Rome, merges a vibrant naturalism with the formal language of classicism in a grand and monumental style. Annibale was also instrumental in evolving the 'ideal', classical landscape and is generally credited with the invention of Caricature.

I. Life and work.

1. Paintings.

(i) Bologna, 1560-95.

According to his biographer Malvasia, Annibale was taught painting by his cousin Ludovico, who early recognized the younger man's talents and sent him on a study trip through northern Italy-the so-called studioso corso-to acquaint him with the great tradition of Lombard and Venetian Renaissance painting. Malvasia published two letters purportedly written by Annibale to Ludovico in April 1580 from Parma, in which he expressed his enthusiasm at discovering Correggio's art. Whether or not these letters are fabrications, as has been alleged, it is beyond question that Annibale visited Parma, Venice and other north Italian cities in the early 1580s and that he made careful study of the paintings he saw there.

Annibale Carracci: Butcher's Shop (Oxford, Christ Church Picture Gallery); Photo…Since nothing certain is known of Ludovico's work before c. 1584, the actual extent of his influence on his cousin's formation cannot be determined. That Annibale was also influenced-if not necessarily taught-by Bartolommeo Passarotti, one of Bologna's chief Mannerist artists, can be deduced, however, from his earliest surviving paintings. These depict genre subjects of a kind popularized by Passarotti and are executed in a broad technique that resembles that used by the older master for such works. Annibale's early genre paintings (c. 1581-4) vary from unassuming head studies and exercises in foreshortening, such as a Drinking Boy, known in several versions, and the Dead Christ (Stuttgart, Gemäldegal.), to more complex pieces, such as the large and ambitious Butcher's Shop (Oxford, Christ Church Pict. Gal.) or the stupendous Bean Eater (Rome, Gal. Colonna). Despite their superficial resemblance to works produced by Passarotti and his studio, these pictures are remarkable for the unprecedented directness and sympathy with which they present their simple subjects; light and colour are handled to a maximum effect of naturalism, and the summary brushwork helps to render a first impression as directly as possible.

This freshness of vision also distinguishes Annibale's first major religious work, the Crucifixion with Saints (1583; Bologna, S Maria della Carità), a surprisingly powerful work for a 23-year-old artist. The composition-six figures crowded together in the foreground, arranged symmetrically around the cross-derives from Passarotti, but the bold naturalism with which the massive and slightly awkward figures are presented is novel. There is little sense of elegance or artifice. Annibale presented the sacred figures as belonging to the same world as that inhabited by the butchers and tradesmen of his genre pictures, using the same vigorous, at times coarse, technique, though there are also passages of great painterly beauty, which indicate direct knowledge of Venetian painting. The transposition of an 'informal' technique appropriate to low-life paintings to a religious work destined for a public location was deemed revolutionary. Not surprisingly the Crucifixion was vehemently attacked by older Bolognese artists, who were offended by the absence of finish and artifice. The fact that the Carracci had by 1583 set up their own academy and were attracting students away from the established studios no doubt played its part in the Crucifixion's critical reception. Despite all censure, the work evidently impressed local patrons enough to ensure that further commissions soon followed.

The Baptism in S Gregorio, Bologna (commissioned in 1583, installed in 1585), shows the artist widening his horizons. The figure style and the clumsy composition attempt to emulate Correggio; the high-keyed palette of the upper portion of the painting, showing God the Father in a glory of angels, reveals the impact of the work of Federico Barocci. Over the next few years, Annibale continued to explore what Barocci and especially Correggio could teach him. The lithe and supple figures and the warm local colours that characterize his contributions to the friezes in the Palazzo Fava, Bologna (1583-4; see §I, 2 above), derive from lessons learnt from them. The altarpiece that Annibale executed in 1585 for the Capuchin church in Parma, the Pietà with SS Francis and Clare (Parma, G.N.), reveals a deeper reflection on the art of Correggio. Its composition is more tightly structured than before, and the figures, particularly those in the lower half of the painting, move within a believable space; through pose and gesture, they actively engage the viewer's response. Annibale adopted a Correggesque sfumato within a restricted range of warm, earthy browns and reds. The fall of light serves to heighten the painting's expressive impact. In all respects the Pietà heralds later developments, and it has rightly been called the 'first Baroque picture' in Italy (Mahon, 1947, p. 274). Baroque tendencies are even more explicit in the Assumption of the Virgin (1587; Dresden, Gemäldegal.), painted for the Confraternity of St Roch in Reggio Emilia.

The frieze with the Stories of the Founding of Rome (Bologna, Pal. Magnani-Salem) most likely dates from 1589-90. Annibale painted three of the narrative frescoes (Remus Fighting the Cattle Thieves; Remus Brought before King Amulius and Romulus Marking the Boundaries of Rome) and contributed designs for some of the other scenes. The ornamental framework, richer and more complex than that of the Fava friezes, was probably also designed by Annibale, who executed at least one of the groups separating the panels. The increased complexity and energy of the Magnani frieze owe much to Annibale's study of the great Renaissance masters of the Venetian school. Between 1588 and 1595 Venetian influences dominated his work. Agostino's prints after Venetian paintings provided a rich source of inspiration, but presumably Annibale also visited the city again in late 1587 or 1588. He explored the various possibilities offered by the different painters of Venice, testing their solutions against what he could observe in nature. Thus the Virgin of St Matthew (1588; Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister) is an obvious paraphrase of Veronese, but transposes the latter's courtly idealism into a more robust, almost homely realism. The Venus, Satyr and Two Cupids (c. 1588; Florence, Uffizi), a free variation on a composition by Titian, heightens the sensuousness of its model to a marked degree.

Venetian and Veneto-Flemish examples also influenced Annibale's early landscape paintings, such as his Hunting and Fishing scenes (c. 1587; Paris, Louvre). These pendant canvases are essentially genre scenes set out of doors, with numerous figures in contemporary dress engaged in everyday activities in a landscape setting. Presumably the genre pictures and landscapes were mainly produced for decorative settings, but after c. 1588 Annibale no longer felt the need to accept minor commissions for decorative settings or portraits, although he seems to have painted the occasional landscape for his own pleasure. The River Landscape (c. 1589-90; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) is an early example of a 'pure' landscape, in which the human presence has become incidental. Portrait painting, a genre that Annibale had occasionally practised in his early years (e.g. the portrait of ?Claudio Merulo, 1587; Naples, Capodimonte), likewise virtually disappeared from his oeuvre at this time.

Annibale next attempted to unite powerful Lombard naturalism with central Italian principles of design. A first indication of this process is found in the Virgin of St Louis (probably c. 1589-90; Bologna, Pin. N.). The rich painterly effects and colour remain Venetian, but the figures are given a new compactness, and their gestures and expressions are more idealized. The composition itself, a design of subtly balanced diagonals, is symmetrical and essentially static. Such features indicate that Annibale consciously sought to moderate the Baroque tendencies of his earlier work with a measure of classical restraint. The increasingly monumental, dated altarpieces of 1592-3 document his striving towards a new equilibrium: the Assumption of the Virgin (1592; Bologna, Pin. N.), the Virgin of St Luke (1592; Paris, Louvre) and the Virgin with SS John and Catherine (1593; Bologna, Pin. N.). The outcome is magnificently illustrated by the Resurrection (1593; Paris, Louvre). Powerful and clearly delineated figures are set before a splendidly poetic landscape. A suggestion of explosive movement is created by the pattern of diagonals emanating from the sealed tomb in the picture's centre, but these forces remain firmly contained within a closed and harmonious composition. While the figures have the solidity and formal regularity of Classical sculpture, the power of naturalistic description is such that they remain convincing as living beings. By such means, the viewer is persuaded to accept the reality of the supernatural event, even as the degree of idealization removes it from everyday experience. The closely contemporary Venus Adorned by the Graces (c. 1594; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) illustrates this stylistic phase in a more sensuous mode.

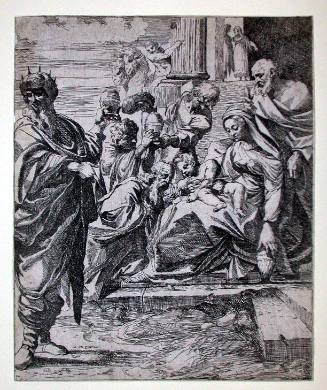

In the late summer of 1594 Annibale left Bologna, with Agostino, in response to an invitation received from Cardinal Odoardo Farnese. Before moving definitively to Rome in 1595, Annibale briefly returned to Bologna in order to finish outstanding commissions. Chief among these was St Roch Distributing Alms (Dresden, Gemäldegal. Alte Meister), which had been commissioned as early as c. 1587 for the church of S Prospero in Reggio Emilia. The huge canvas, containing many more figures than any previous work by Annibale, thus became the final statement of his Bolognese period and his most felicitous synthesis of classical rhetoric and Lombard naturalism to date. The composition's firm structure owes as much to Raphael as it does to Veronese; as in the late works of Raphael, the many figures all contribute to convey the moral sense of the event. With the St Roch, Annibale created the first great history painting of the Baroque.

(ii) Rome, 1595-1601.

(a) Camerino Farnese, c. 1596-7.

Annibale Carracci: Hercules at the Crossroads, oil on canvas, c.…On arriving in Rome, Annibale was given lodgings in the Palazzo Farnese. Here he was asked to paint the ceiling of the Cardinal's private study (c. 1596-7). This room, known as the Camerino Farnese, is small (c. 4.8×9.4 m) with a coved ceiling penetrated by six triangular spandrels over semicircular lunettes. The iconographical programme of the frescoes, probably devised by the Farnese librarian Fulvio Orsini, alludes allegorically to the virtues of the patron. The principal scenes show Hercules Bearing the Globe, Hercules Resting from his Labours and Hercules at the Crossroads. These are treated as quadri riportati (simulated easel paintings), the last-named central scene being actually painted on canvas (Naples, Capodimonte; replaced with copy in Rome). A network of gilt stucco bands connects the three scenes and further divides the ceiling into irregular fields, filled with painted ornament simulating stuccowork. Small mythological and allegorical figures are contained within fictitious reliefs painted in chiaroscuro. In the four lunettes on the walls, Annibale represented Ulysses and Circe, Ulysses and the Sirens, Perseus and Medusa and the Catanian Brothers Carrying their Parents.

The decorative scheme of the ceiling, indebted to Mantegna's Camera degli Sposi (Mantua, Pal. Ducale; see fig.), is north Italian in origin, and the same holds true for the style of the ceiling paintings. Though the first traces of Annibale's direct observation of Roman antiquities and of Michelangelo are visible in some compositions and individual figures, such quotations are contained within a whole that does not, as yet, differ significantly from his most recent Bolognese work. Only in the central canvas, Hercules at the Crossroads, is there a more insistent reference to antique sculpture, a tautening of outline and an aggrandizement of forms that serve to give the figures an appropriately 'antique' air.

Annibale's development during the years 1597-1601 is one of progressive assimilation of the principles of Roman classicism: the confrontation with the city's artistic monuments, both ancient and modern, prompted him to adjust his synthesis of northern colourism and central Italian design. There is no sudden shift of allegiance: on the contrary, the influence of Correggio, in abeyance since the late 1580s, enjoyed a sudden and remarkable revival in Annibale's early Roman works (e.g. the Coronation of the Virgin, New York, Met.; the Archangel Gabriel, Chantilly, Mus. Condé), though now seen through a Raphaelesque prism.

(b) Ceiling of the Galleria Farnese, 1597-1601.

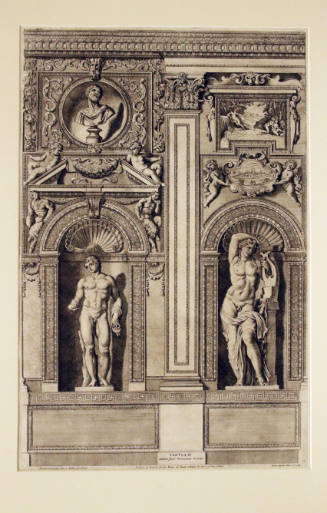

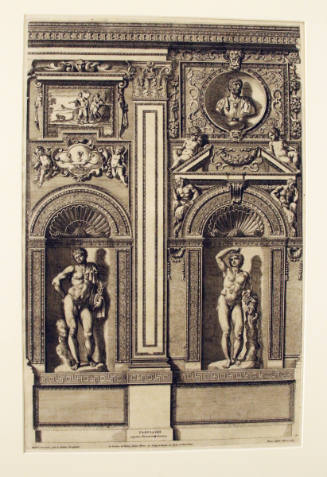

Annibale Carracci: Loves of the Gods (1597-1601), vault fresco, Galleria…A wholehearted conversion to classical ideals was powerfully supported, however, by the requirements of Annibale's next major task, the decoration of the ceiling of the Palazzo Farnese's gallery (see fig.). The Galleria Farnese is a long and relatively narrow room (20.14×6.59 m) covered by a barrel vault. Annibale illustrated the set theme-the power of love-with scenes from Classical mythology, which unequivocally and joyfully celebrate profane love as an all-conquering force to which even the Olympian gods are subject. It is unlikely that the programme was intended to convey a moral or religious message, as was formerly thought; the frescoes offer little support for Bellori's reading of them as an allegory of the struggle between Heavenly and Earthly love. The choice of mythological subject-matter appears to have been prompted largely by the fact that the gallery contained some of the finest antique statues of the Farnese collection. Nor does it seem that Annibale was given a highly detailed programme to follow: his preparatory drawings show that devising the ornamental framework took precedence over, and in some cases even determined, the choice of incidents to be included.

Annibale Carracci: Polyphemus Attacking Acis and Galatea (1597-1601), ceiling fresco…The vault confronted the artist with a task unlike any he had undertaken before, both in terms of size and of complexity. For an indeterminate period between October 1598 and the autumn of 1599, he was helped by Agostino, who painted the two large narrative scenes above the gallery's long walls. Others assisted in painting minor parts of the frescoes, but the ceiling is to all intents and purposes Annibale's single-handed creation. Actual execution was probably begun in 1598; the preceding months were used to work out a satisfactory framework for the frescoes. Surviving studies and copies of lost drawings document the evolution of the design (see §II, 2 below), which combines elements from various sources in a novel and inventive way. The vault is conceived as being open to the sky. A painted frieze of alternating mythological paintings and feigned bronze roundels, separated by pairs of atlantids and terms painted to resemble stucco sculptures, illusionistically continues the architectural division of the gallery's lower walls on the ceiling. In front of the frieze and partly obscuring it are four quadri riportati in gilt frames, one on each wall, showing episodes from Ovid's Metamorphoses (see fig.). These pictures are imagined as being propped on top of the gallery's walls; the two vertical ones on the short walls illusionistically project forward into space. Other quadri riportati, some in the guise of tapestries, others framed as if they were easel pictures, are strung across the crown of the vault. Interspersed among these make-believe paintings and sculptures are various flesh-and-blood figures: putti who play on top of the roundels in the frieze, satyrs seated on the frames of the vertical paintings and nude youths who sit at the terms's feet holding garlands punctuated with masks. Where the painted friezes meet at the four corners of the room, pairs of cupids (Eros and Anteros) are seen playing against a backdrop of blue sky.

The germs of Annibale's invention are to be found in Raphael's Vatican Loggie and, above all, in Pellegrino Tibaldi's frescoes in the Sala di Ulisse (Bologna, Pal. Poggi), where a similar mixture of quadratura framework, simulated easel paintings and 'living' beings is found. Several ornamental motifs recall the Carracci frieze in the Palazzo Magnani, in particular the combination of 'stone', 'bronze' and 'living' figures peopling the vault, while others refer to Raphael's Farnesina Loggia. The decoration's firm integration into the room's architecture-real and imagined-also owes much to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; the ignudi are only the most obvious references to Michelangelo. Significantly, Annibale rejected Parmese solutions entailing a pronounced sotto-in-sù illusionism in favour of Roman prototypes. But, while the decorative structure of the gallery is in a sense a compendium of 16th-century Roman ideas, the sheer inventiveness of its organization and its brilliant naturalism opened up the way for the great Baroque ceilings of the 17th century. The levels of fictitious reality in the Galleria Farnese are both more complex and are handled with much greater logic and persuasiveness than in any of its predecessors. The effect of the whole is that of a colourful imaginary 'picture gallery', richly decorated with bronze and stone sculpture, placed on top of the real sculpture gallery below.

This effect relates to a secondary theme of the frescoes, which is the power of art, and of the art of painting in particular. Annibale's frescoes can be interpreted as a mock-serious statement of his views on the Paragone, the 16th-century debate concerning the relative merits of sculpture and painting. Such an interpretation is supported by the many allusions to sculpture to be found in the paintings, most obviously in the 'bronze' reliefs and 'stucco' sculptures but also in the narrative scenes, which contain numerous quotations of renowned statues. In the ceiling Annibale used his command of optical verisimilitude to conjure up various levels of reality, each equally persuasive, in a dazzling and witty display of painterly virtuosity. The ignudi and the putti, imagined as being part of the spectator's world, are distinguished from the mythological beings peopling the quadri riportati, who are treated in a more idealizing manner, which again invites comparison with ancient sculpture. Yet at the same time supposedly sculpted figures such as the stucco terms and atlantids or the masks seem equally alive; they exchange glances, grimace and otherwise react to events in the narrative scenes or to the spectator on the gallery's floor. The frescoes thus proclaim the painter's skill in creating a duplicate world and encourage the viewer to marvel at the power of his art.

The rich profusion of decorative elements endows the Farnese ceiling with an air of festivity and joyous energy that is maintained within the single scenes. The largest quadro riportato, the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne placed in the centre of the vault, shows a romping train of satyrs and maenads accompanying the god of wine and his bride. The impression may be of riotous abandon, but the figure groups are contained within a symmetrical and carefully balanced composition of strict classical design. For inspiration, Annibale turned to ancient Bacchic sarcophagi; other famous prototypes, both antique and modern, served for individual figures. In general, the Farnese ceiling exhibits a degree of idealization and classicism greater than anything Annibale had painted before. The figures are aggrandized far beyond the norms set by his previous works, with enlarged features and heroic, sculptural bodies. Outline assumes a greater importance in communicating shape and content; the use of colour tends to isolate each figure from its surroundings. In part such features would have been prompted by the formal requirements of the decoration: the legibility of the frescoes from the gallery's floor some 10 m below was clearly an important consideration. The Classical imagery of the ceiling must also have stimulated Annibale to develop an appropriately classicizing language, as must the inevitable comparison with Raphael's Loggia of Cupid and Psyche in the Villa Farnesina.

(c) Other works.

The gallery's vault was finished and unveiled in May 1601. Despite the fact that the ceiling occupied most of Annibale's time and energy between 1597 and 1601, a considerable number of easel works can also be dated to the same years. These include the Adoration of the Shepherds (Orléans, Mus. B.-A.), a 'romanized' version of a composition created by Correggio; the small Temptation of St Anthony on copper (London, N.G.); the large Nativity of the Virgin for the basilica in Loreto (Paris, Louvre) and a medium-sized altarpiece commissioned by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, Christ in Glory with Four Saints and the Donor (Florence, Pitti). The most impressive religious picture of these years is the Pietà (c. 1599-1600; Naples, Capodimonte), likewise painted for Cardinal Odoardo. It blends memories of Correggio and Michelangelo in an image of great emotional power. The Pietà is to 16th-century religious painting what the gallery's ceiling is to secular decoration: a recapitulation of past achievements and a signpost to new developments. The Landscape and River Scene (c. 1596; Berlin, Gemäldegal.) occupies a similar position for landscape painting, integrating Venetian naturalistic elements into a firmly structured design and pointing forward to the invention of the ideal landscape.

(iii) Rome, 1601-9.

Before the unveiling of the Farnese ceiling, Annibale was relatively little known in Rome. The first painting by his hand to appear in a public location within the city was a small altarpiece of St Margaret in S Caterina dei Funari (installed 1599), a variant replica of a figure in the Virgin of St Luke of 1592 and stylistically still part of his late Bolognese years. The radical transformation of his style since he came to Rome could not be appreciated fully until his altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin for the Cerasi Chapel in S Maria del Popolo was unveiled early in 1601 (in situ). Despite the panel's relatively modest size, it has an overpowering impact. Supported by angels, the Virgin erupts from the empty tomb around which the apostles crowd, compressed together in the immediate foreground. Forms are simplified, and the almost geometrical solidity of the figures is intensified by the bright colours and sharp focus typical of panel painting. A staccato tempo of abrupt gestures, sudden twists and turns and unexpected juxtapositions forcefully communicates the picture's dramatic content, replacing the gentler, lyrical rhythms of the Pietà or the Farnese ceiling. The fact that the Assumption was to be flanked by two paintings by Caravaggio no doubt contributed to its extremist position. Faced with the challenge posed by Caravaggio's anti-idealist style, Annibale took the opposite course. His altarpiece polemicizes Caravaggio's non-selective naturalism, countering it with a conception of religious painting in which sacred figures of idealized perfection are depicted with the greatest possible verisimilitude; a conception that, moreover, had the full authority of tradition behind it.

Annibale Carracci: Rinaldo and Armida (Naples, Museo e Galleria Nazionale…In his pursuit of an ideal truth that would be emotionally compelling, Annibale turned to the late works of Raphael. It is the latter's designs for the Sistine Chapel tapestries and the Transfiguration that determine the last distillation of Annibale's classical style. The Cerasi altarpiece initiates that final development, which has been termed 'hyper-idealism' and which took place in the years 1601-4. These were some of the busiest years of Annibale's life. Cardinal Odoardo put him in charge of the decoration of the Palazzetto Farnese, a casino in the garden of the Palazzo Farnese. Within the palazzo itself, the walls of the gallery awaited decoration. The unveiling of the gallery's ceiling, moreover, multiplied demand for Annibale's work, and he accepted several prestigious commissions from other patrons. It must have been obvious that the amount of work awaiting him called for the help of more, and abler, assistants than he had had so far. It seems he used a visit to Bologna, occasioned by Agostino's death in February 1602, to persuade a number of students working in the Carracci Academy to join him in Rome. Francesco Albani, Domenichino and Agostino's young son Antonio soon arrived from Bologna, while Lanfranco and Badalocchio, previously Agostino's pupils in Parma, likewise joined the studio. The first task awaiting the students was the decoration of the Palazzetto Farnese. The walls and ceilings of the casino's rooms were to be adorned with paintings and frescoes, many of them supplied by Annibale's shop, in some cases following his designs. Surviving pictures by the master himself from this project are the Sleeping Venus (c. 1602; Chantilly, Mus. Condé), an intensely classicizing work illustrating a text by Philostratus Lemnius, and the Rinaldo and Armida (Naples, Capodimonte), executed with the help of an assistant.

Payments for scaffolding for the decoration of the walls of the Galleria Farnese start in May 1603; the frescoes were finished before the end of 1604. Annibale himself painted relatively little, leaving most of the project to his assistants. With some studio intervention, he executed the two large scenes on the short walls: the Rescue of Andromeda and Perseus and Phineus. Above the central doorway facing the windows is a fresco of the Virgin with a Unicorn, painted by Domenichino from Annibale's cartoon. Interspersed among the stucco decorations along the long walls are small mythological scenes painted by assistants from sketches provided by the master. Members of the shop were responsible also for the four Virtues painted in the end bays of the long walls and for the imprese of various members of the Farnese family.

The frescoes on the gallery's walls differ markedly in temper from the Loves of the Gods on the ceiling. Whereas the ceiling exudes an air of libidinous festivity, the wall paintings display a sombre, moralistic mood. According to Bellori, they are to be interpreted as allegories of the virtues possessed by the Farnese family. Thus Perseus Rescuing Andromeda would symbolize Reason freeing the Soul from Vice, and its pendant, Perseus and Phineus, the Triumph of Virtue over Lust. The presence of Virtues, the Virgin and the Unicorn and the Farnese imprese lend some support to such an allegorical reading. It has also been suggested, though, that the wall frescoes continue and expand a theme adumbrated in a more playful fashion on the ceiling, namely the allusion to paragone and the nature of art. The two Perseus episodes, concerned with living beings turned into stone, most obviously lend themselves to such a reading, but many of the smaller scenes along the long walls-the Fall of Icarus and the Prometheus scenes, among them-can also be seen as allegories of the power of art. If the thematical divergence of the frescoes on the walls from those on the ceiling may therefore have been overestimated, there is no questioning their great disparity in style. Instead of the joyous interweaving in bright sunshine of plastically rounded forms seen on the vault, the wall frescoes display a harsh and stony world of muted colours, where block-like figures are frozen in angular attitudes and from which all sensuousness of depiction has been banned. This is particularly so in the two Perseus scenes painted by Annibale himself, where the geometrical, hard-edged style first encountered in the Cerasi Assumption is further developed.

One of Annibale's most admired paintings, the Pietà (or the 'Three Maries'; London, N.G.), displays many of the same characteristics and is most likely to date from the same years. It is the final result of a lifelong fascination with Correggio's painting of the subject in Parma. Though the influence of this prototype is still perceptible, its emphasis on the affetti, the 'movements of the soul', gives it a wholly new meaning and places it squarely within the 17th century. A similar emotionality invests the Pietà with St Francis (Paris, Louvre), painted for the Mattei Chapel in S Francesco a Ripa, a work largely executed in 1603 but left unfinished until c. 1607, and the small Stoning of St Stephen on copper (c. 1603; Paris, Louvre). The latter work is particularly innovative in that it applies the rules of monumental design to small-scale history painting.

Early in 1605 Annibale succumbed to an apoplectic attack brought on, it seems, by physical exhaustion. Though he recovered enough to accept new commissions later that year, the attack left him prey to a profound melancholy, which was exacerbated by the lack of appreciation shown him by his main patron, Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, who paid a mere 500 scudi for his labours in the Galleria Farnese. Annibale, deeply wounded by this slight to his honour, left the Cardinal's service in August 1605 and found lodgings on the Quirinal Hill. Illness and depression compelled him to relinquish most of his outstanding commissions to his pupils. In 1603-4 he had agreed to paint six lunettes with New Testament scenes in a landscape setting for the chapel in the palazzo of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini (Rome, Gal. Doria-Pamphili). Before 1605 he had painted one of the lunettes, the Flight into Egypt, and designed the Entombment. The Flight into Egypt is the archetypal statement of what has come to be known as the 'ideal landscape', a rationally constructed landscape in which human figures, buildings and nature are held in perfect balance. In 1605 the commission was turned over to Albani, who finished the Entombment and, with the help of other assistants, executed the remaining four lunettes. Annibale had in 1604 also contracted to paint the chapel of Juan Enriques de Herrera (destr.) in S Giacomo degli Spagnuoli (frescoes and altarpiece divided between Madrid, Prado; Barcelona, Mus. Catalunya; and Rome, S Maria di Montserrato). The master designed all the frescoes and executed some of them before March 1605, when illness forced him to put Albani in charge of the remainder. Despite the resulting unevenness of execution, the spare and sober Herrera frescoes are important testimonies to the final phase of Annibale's development.

Annibale's last years were marked by deep melancholia and artistic sterility. He appears to have worked only sporadically, though continuing to supervise the few paintings put forth in his name by his students (altarpieces in S Onofrio, Rome, and in the Farnese Chapel in the abbey church at Grottaferrata). In July 1608, in an attempt to get him to work again, his remaining students drew up a contract in which each member of the studio undertook to finish at least one small painting every five weeks. The attempt seems to have had little, if any, effect. Following a visit to Naples in the company of the young Bolognese painter Baldassare Aloisi (1577-1638), Annibale died in Rome. An inventory of his meagre belongings drawn up shortly afterwards lists several unfinished paintings, none of them identifiable. According to his wish, Annibale was buried in the Pantheon.

2. Drawings.

All three Carracci were consummate draughtsmen, but Annibale especially has always been esteemed as one of the greatest draughtsmen in Western art. His drawings show an apparently effortless grasp of shape and structure, together with an extraordinary sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Thematically they cover a wide range. Figure studies and other kinds of preparatory drawings predominate, but there are also numerous sheets without such a specific purpose, particularly from his early years. These document his lively interest in the world around him and his keen powers of observation; among them are domestic scenes, portrait studies, sketches of beggars and vagrants, and scenes witnessed in the streets of Bologna. In the 1580s Annibale produced a series of drawings of ambulant tradesmen in characteristic costumes (one survives; Edinburgh, N.G.). These drawings, apparently made for the artist's own pleasure, were later engraved and published by Mosini as the Arti di Bologna (Rome, 1630).

Another area of interest was landscape: drawn landscape studies survive from all phases of his career. Mostly in pen and ink, they generally appear to have been done in the studio; none can be related to extant paintings or prints. Early landscape drawings show clear Venetian influence in arrangement and poetical mood, while the landscapes of the last Roman years are much starker, becoming almost 'stenographic' in their economical notation of form and light. Relatively few life studies of a model in an 'academic' pose can reliably be attributed to Annibale; generally accepted examples all date from his early years.

Most of Annibale's surviving drawings were made in preparation for painted compositions. Early figure drawings and composition studies are concerned with the distribution of light and shadow rather than outline; they exploit a variety of colouristic techniques in strong chiaroscuro. Influenced by Correggio's draughtsmanship, the young Annibale preferred red chalk for figure studies, often smudging the chalk or combining it with red wash or white heightening to obtain a richer, more atmospheric effect. Occasionally he used a lightly oiled black chalk or charcoal in a similarly soft manner. Pen drawings of the early years are frequently enriched with differently coloured washes or make use of tinted paper; unlike the chalk drawings, they show a clear debt to the older generation of Bolognese draughtsmen. As his style matured, Annibale's drawings became more disciplined. The predominance of black chalk from c. 1588 onwards, often in combination with white chalk on blue or grey paper, appears to be due to Venetian influence.

Once Annibale had moved to Rome, the graphic definition of form and anatomical structure assumed greater importance. The celebrated figure studies for the Farnese ceiling show a simplified chalk technique: shading is used mainly within well-defined contours to modulate form, and the painterly softness of earlier studies gives way to a more sculptural treatment. Human form is now conceptualized and idealized beyond the particular. Annibale's later pen drawings likewise became more sparing in their use of wash, until in his last years they acquired a harsh, inelegant aspect that is as expressive as it is unprecedented.

Always admired, Annibale's drawings were collected from an early date. In the 17th century, the Roman Francesco Angeloni, a friend of Agucchi and Bellori, owned no less than 600 drawings connected with the Galleria Farnese; these were acquired by the French painter Pierre Mignard and were subsequently owned by Pierre Crozat and Pierre-Jean Mariette before being dispersed. (The two largest actual holdings are in the Louvre, Paris, and in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Important and representative groups are also to be found at Chatsworth House, Derbys; the Uffizi, Florence; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Ashmolean, Oxford; and the Albertina, Vienna. Most print rooms contain at least some examples.)

Sources from the 17th century almost unanimously credit Annibale with the invention of caricature. However, no true caricatures survive that can be securely attributed to him. It therefore remains speculative whether it was Annibale or Agostino (by whom true caricatures are known) who was primarily responsible for the invention of the genre.

3. Prints.

Annibale's proficiency as a draughtsman relates directly to his accomplishment as a printmaker. Though his output in the medium is limited-only seven finished engravings and twelve etchings can be attributed to him-his prints are of exceptional quality. Apart from two reproductive engravings produced at the beginning of his career, he worked only from his own inventions. It was Agostino who instructed Annibale in the technique of engraving, and the earliest prints reliably attributed to the latter (e.g. the Crucified Christ, 1581; b. 5) follow the older brother's manner. A more personal style of engraving is first encountered in the small St Jerome (c. 1583-5; b. 13). Annibale's engravings reveal a greater feeling for texture and atmosphere than do Agostino's, and he showed more interest in establishing mood. He had a marked preference for etching, exploiting its spontaneity and resemblance to pen drawing to great effect. The etching of the Holy Family with St John the Baptist (1590; b. 11), a tender domestic scene rendered with short, vibrant strokes creating a soft luminosity, is a typical example. This etching manner is developed in the St Jerome in the Wilderness (b. 14) and the Susanna and the Elders (b. 14), both datable to the early 1590s.

The Pietà (or 'Christ of Caprarola', 1597; b. 4) is Annibale's most famous work in the medium. It combines the techniques of engraving, etching and drypoint in a technically intricate image of great originality and emotional power. The only other print dating from Annibale's years in the service of the Farnese is the engraving of the Drunken Silenus (c. 1598-1600; b. 18). It was pulled from a silver platter that he engraved, the so-called Tazza Farnese (Naples, Capodimonte). A companion piece, a silver bread basket known as the Paniere Farnese (Naples, Capodimonte), was likewise designed by Annibale but was engraved by Francesco Villamena. In imagery and style, both works are intimately related to the Farnese ceiling.

Annibale returned to printmaking in 1606, the date of the Madonna della scodella (b. 9) and Christ Crowned with Thorns (b. 3). Both are powerful examples of his expressive late style, with simplified, bulky forms looming large in the picture field. An undated Adoration of the Shepherds (b. 2) was designed in 1606 or possibly even later.

II. Working methods and technique.

The Carracci reinstated the Renaissance practice of making life studies in preparation for painted compositions. Annibale carefully considered beforehand a picture's composition, the poses of individual figures it contained and the distribution of light and shadow within it, before actually beginning to paint. Surviving drawings, especially of his Bolognese period, provide ample evidence of his continuous referral to nature and the model. In Rome, faced with the vastly more complex decorative projects for Cardinal Farnese, Annibale's preparatory processes became even more laborious, as the numerous studies for the Camerino and especially those for the ceiling of the Galleria Farnese attest. All the classic preparatory stages are represented in the surviving material related to these projects: rapid compositional sketches, more elaborate general studies that clarify the distribution of light, life studies of individual figures and anatomical details and full-scale cartoons. His working methods thus conformed to established central Italian traditions. Annibale is said by Bellori to have made preparatory colour sketches or oil bozzetti in the Venetian tradition, but no undisputed examples are known.

Whether in oils or fresco, Annibale's painted works display an admirable crispness of detail and a masterly technique. The roughness of touch that characterizes the early genre paintings and the Crucifixion of 1583 was supplanted soon thereafter by a smoother handling influenced by Correggio's carefully glazed paintings. Yet the Bolognese canvases in general continue to display a fondness for painterly effects of Venetian origin; the variegated texture of brushstrokes helps create an impression of movement and shifting light, and a more refined variant of the broken touch of the genre paintings occasionally resurfaces in paintings with a decorative purpose (e.g. the River Landscape of 1590). Even in his Roman period, when naturalism was no longer a function of technique but of drawing and the paint surface of his pictures had generally become tighter and more uniform, Annibale remained sensitive to painterly effects, as demonstrated in the marvellous suggestion of nature in movement in the Aldobrandini Flight into Egypt.

Annibale has generally not been rated very highly as a colourist. It is true that he was not particularly innovative in his use or choice of colours, and colouring in his paintings-even the earliest ones-is usually subservient to design. That he nonetheless had a thorough understanding of the laws of colour and optics is clear from his Bolognese paintings, which contain splendidly poetic passages of pure colour. In its different way, the Farnese ceiling is an unparalleled masterpiece of bright, naturalistic colour applied in true fresco. It is only in the works of his last years that Annibale renounced altogether the sensuous appeal of colour to concentrate on the rendering of the affetti through gesture and facial expression.

Annibale transmitted his working methods to his pupils. According to 17th-century writers, Annibale's training of studio assistants to imitate his manner was a second aspect of his reform: not since Raphael had Rome witnessed a comparable school of talented artists harmoniously working together under the direction of one master. In Bologna, Annibale did not have pupils in the strict sense: students attending the Carracci Academy were instructed by all three leading members of the family. And while he did have assistants, such as Innocenzo Tacconi between 1595 and 1602, who helped him paint the Farnese ceiling and other works, it was not until 1602 that a true school formed around the artist. Its members, most of them far more talented than Tacconi, included Albani, Domenichino, Lanfranco, Badalocchio, Antonio Carracci and the Milanese G. A. Solari (c. 1581-1666). More loosely associated with the studio were Antonio Maria Panico (c. ?1570-c. 1620), in the service of another member of the Farnese family, and the landscape specialist Giovanni Battista Viola.

It was thus only from 1602 that Annibale had an opportunity to mould the talents of young artists. He taught them not only through his own example but also by encouraging them to study the monuments of Roman art on which he had based his late manner: works such as the Laokoon (Rome, Vatican, Mus. Pio-Clementino), the Vatican Stanze and the Sistine Chapel, Raphael's Loggie and the like were copied, dissected and analysed by the master and his students. Annibale used his pupils' assistance in various ways. In a large commission, such as the walls of the Galleria Farnese, he let them execute subsidiary scenes according to his designs and under his close supervision. In the Palazzetto Farnese, on the other hand, the pupils contributed frescoes and canvases with minimal help from the master. The easy partnership between peers that had characterized the Carracci shop in Bologna appears to have influenced Annibale's collaboration with his pupils in his Roman studio. He sometimes let them execute minor passages in his own works, and at other times he intervened in works substantially designed by one of the pupils, either by providing drawings or by correcting or adding some passages himself. The students were given considerable stylistic latitude, even in projects for which Annibale bore nominal responsibility; the walls of the Galleria Farnese and the Herrera Chapel frescoes are cases in point. However, the circumstances under which these works had to be executed, under great pressure of time and speed, and the illness that struck Annibale early in 1605 no doubt made this a practical rather than a desirable solution. Through his teaching and example, Annibale successfully inculcated the principles of his style in his pupils, thus initiating a school, the influence of which was to last well over two centuries.

III. Character and personality.

Very little written material survives by Annibale Carracci's own hand. Most revealing are his marginal notes in a copy of Vasari's Vite (Bologna, Bib. Com. Archiginnasio), in which he vented his fierce indignation at the historian's Tuscan bias and expressed his admiration for those Venetian painters whose achievements Vasari, in his eyes, had belittled. The impromptu annotations provide fascinating insights into Annibale's temperament as well as his stylistic allegiance-virtually all the notes deal with Venetian artists, and the only Bolognese painter to receive favourable mention is Pellegrino Tibaldi-but unfortunately it cannot be established exactly when they were written. Though it has been argued on circumstantial evidence that they were written only after the artist settled in Rome in 1595, the very impulsiveness and indignation of the notes seem more characteristic of Annibale's youth. The strong pro-Venetian sentiment suggests that they were written shortly after a trip to the Republic, perhaps in the years 1588-90, when Venetian influence on Annibale's painting was at its peak.

Aside from these notes, only one letter (Reggio Emilia, Archv Stato), addressed to Giulio Fossi, a patron, in 1595, is indisputably Annibale's. Malvasia published some otherwise unknown letters (and fragments), which he attributed to the artist, but their authenticity has not been universally accepted. Despite the paucity of the evidence, a consistent picture of Annibale's personality emerges from it, when amplified by the accounts of his biographers. They portray him as a warm-blooded man, as choleric as he was compassionate, a man of few words, to whom his personal independence was paramount. Annibale saw himself first and foremost as a painter and preferred the company of craftsmen to that of persons of more elevated rank; the status of courtier, forced on him during his years in the service of Cardinal Farnese, did not suit him and ultimately contributed to his breakdown. Annibale took little heed of his outward appearance, dressing casually like an artisan, and-in contrast to his brother Agostino-set little store by social accomplishments or laymen's acclaim. There are several anecdotes about him sharply deflating Agostino's pretensions by reminding his brother that they were the sons of a tailor, and themselves craftsmen. On the other hand, Annibale took his profession extremely seriously, reacting violently to any real or imagined slight to his stature as a painter. He could be intensely jealous of other artists, notoriously so in the case of the much younger Guido Reni; yet he was an extremely generous teacher.

At several points in his life Annibale painted his own portrait (e.g. c. 1585, Milan, Brera; 1593, Parma, G.N.). The most revealing is the unparalleled Self-portrait on an Easel (c. 1603; St Petersburg, Hermitage), which shows Annibale's portrait on an easel from which his palette hangs, in a gloomy, ill-defined interior. A dog and cat lurk in the foreground; further back, before a window, either a sculpture or a plaster model is seen. Roughly painted with evident haste, this sombre work reduces the artist's portrait to one of several objects in a nondescript space. The artist thus dissociated himself from his own image and work and subjected both to the judgement of the viewer.

IV. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Annibale's standing as one of the foremost painters of his generation was recognized by his contemporaries, as the earliest biographical notices attest (Mancini; Mosini; Baglione). The two standard biographies of the artist were published a generation later, by Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1672) and Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1678): although generally reliable, both are biased, Bellori in favour of the Roman Annibale, Malvasia of the Bolognese. These biases reflect a debate that sprang up shortly after, if not during, Annibale's lifetime, namely whether he had been the greater painter in Bologna or in Rome. It was Bellori's view that Annibale was able to achieve that synthesis of colore and disegno that so successfully restored the art of painting only after he had seen the marvels of Rome; the artist's Emilian period is consequently presented as a prelude to that crowning achievement. The Bolognese Malvasia, on the other hand, sought to emphasize the north Italian roots of the Carracci reform. He believed Ludovico to have been its prime instigator and repeatedly challenged the received opinion that Annibale was pre-eminent. In his eyes, Annibale had abandoned the cause of Emilian painting by defecting to Rome, and he held that the qualitative level of Annibale's art had suffered as a consequence. On the whole, it is Bellori's view, that it was precisely by going south that Annibale was able to consolidate the achievements of the Bolognese reform movement, that has prevailed.

Well into the 19th century, the position of Annibale Carracci as one of Italy's greatest painters remained unassailable. It was not until the advent of Romanticism that the Carracci 'restoration' of painting came to be seen as a reactionary rather than a progressive act. For the first time, the concept underlying the reform-the conciliation of disparate elements of style coupled with renewed study of their basis in nature-was regarded with suspicion and labelled 'eclecticism'. In a remarkably short time this derogatory view of the Carracci's achievement led to a wholesale rejection of it as merely technical and sterile.

Annibale's reputation was slowly revived only in the second quarter of the 20th century, at the hands of a few scholars such as Roberto Longhi, Heinrich Bodmer, Rudolph Wittkower and Denis Mahon. Their publications rescued the Carracci from critical oblivion; Mahon, in particular, sought to remove the stigma of eclecticism that still clung to their works. A large loan exhibition of paintings and drawings of the Carracci, held in Bologna in 1956, offered both a consecration of these efforts and a first possibility for stocktaking.

Other scholars continued to research Annibale's oeuvre, its chronology and its iconographical aspects, culminating in Donald Posner's monograph (1971). Since the later 1970s the scholarly debate has shifted away from problems of attribution and interpretation and come to focus on the role played by theoretical concerns in the daily practice of the Carracci, especially Annibale. At issue is the question of whether or not the Carracci conceived of their pictorial style as a 'method', based in objective theory and therefore capable of being taught to others, or whether the intuitive aspects of painting prevailed in their artistic practice. Those who defend the latter view (including Mahon and Posner) see the Carracci Academy as little different from an extended painters' workshop, despite its somewhat grandiose title, and characterize Annibale as an intuitive artist to whom theory and learning were of little practical value. Others-Dempsey foremost among them-emphasize the role played by theory in the Carracci's practice and contend that the academy was modelled on contemporary literary academies and functioned much as an institution of higher education might. In their eyes, Annibale's approach to painting was shaped by intellectual concerns. The debate hinges to a large extent on the interpretation of two specific sources: the funeral oration for Agostino Carracci, pronounced by Lucio Faberio in 1603, and Malvasia's biographies of the three Carracci, published in 1678. Virtually all current knowledge of the Accademia degli Incamminati and its curriculum depends on these two sources. Whereas Faberio's oration has been shown to be a rhetorical exercise that reveals little about daily practice in the academy in its pre-1595 heyday, Malvasia's account is less easily dismissed. His credibility has been questioned on numerous occasions, but the evidence is far from unequivocal, and in recent years strong arguments have been put forward in support of his essential reliability. Archival research may ultimately resolve the issue. Detailed investigations of Annibale's social background and professional milieu may help to confirm or refute his biographers' otherwise unsubstantiated statements.

There has never been any question, however, that Annibale's achievement was of the highest order or that it brought about a revitalization of the great tradition of Italian Renaissance painting. The principles of the Carracci reform set the course for painting in Italy and France in the 17th century. With greater clarity of purpose and intellectual force than either Ludovico or Agostino, Annibale demonstrated how the past could be revitalized and adapted to contemporary ends. His later Roman work prepared the way for the classical strain of Baroque art, exemplified by his pupil Domenichino and perpetuated by Poussin, Le Brun and the French academic tradition. At the same time Annibale's example helped shape the 'anti-classical' Baroque: Lanfranco, its first great practitioner, was no less receptive a student of his work than was Domenichino. Historically, Annibale's role in Italian painting can be compared only to Raphael's before him. It is evident that the artist himself and his admirers were well aware of the parallel, and it is only fitting that Annibale should be buried in the Pantheon, next to the tomb of Raphael.

C. van Tuyll van Serooskerken, et al. "Carracci." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T014340pg3 (accessed March 22, 2012).