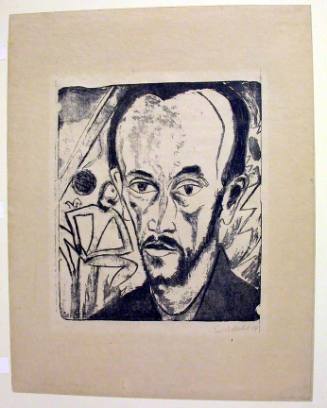

Emil Nolde

German, 1867 - 1956

German painter, watercolourist and printmaker. He was one of the strongest and most independent of the German Expressionists. Nolde belonged to the Dresden-based group known as die Brücke from 1906 to 1907. Primarily a colourist, he is best known for his paintings in oil, his watercolours and his graphic work. His art was deeply influenced by the stark natural beauty of his north German homeland, and alongside numerous landscapes, seascapes and flower paintings, Nolde also produced works with religious and imaginary subjects.

1.Training and early work, to 1912.

Nolde first trained as a wood-carver under Heinrich Sauermann (1842–1904) in Flensburg and worked as a designer in furniture factories in Munich, Karlsruhe and Berlin. From 1892 to 1897 he taught industrial design at the Saint-Gallen crafts museum, during which time he also became known as a mountaineer. The commercial success he enjoyed with a series of postcard drawings depicting the Swiss mountains as characters from fables and fairy tales finally won him the freedom to become a full-time artist, as their sale guaranteed him an income for several years. Studying in Munich at the private school of Friedrich Fehr (b 1862) in 1898, and then under Adolf Hölzel in Dachau (1899), Nolde initially attempted an original synthesis of Symbolism and Realism, drawing on his enthusiasm for the works of Arnold Böcklin and Wilhelm Leibl. In 1900 he studied for several months at the Académie Julian in Paris, during which time he acquired a first-hand knowledge of Impressionist painting. His visit to the Exposition Universelle (1900) awakened his long-standing interest in exotic cultures. Following his marriage to Ada Vilstrup in 1902, when he changed his surname to the name of his home village, Nolde established a yearly rhythm to his life, spending the winter months in Berlin and his summers on the north German island of Alsen.

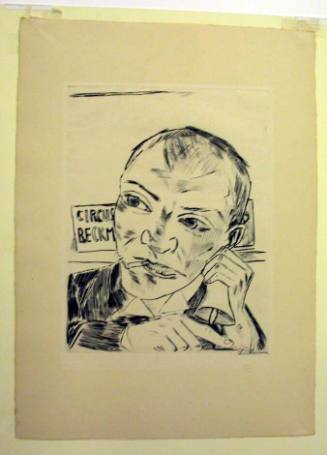

It was the bright, rich colours in such paintings as Springtime in the Room (1904; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde) that attracted the attention of the young Die Brücke artists and prompted them to invite Nolde to join their group in 1906. Although he remained an active member for only one year, Nolde stayed in close touch with Die Brücke. These younger Expressionists encouraged Nolde’s preference for bright colours and free brushwork, and his boldly carved woodcuts date from his contact with the group. However, Nolde’s first series of intensely original and technically experimental etchings, Fantasies (1905, e.g. Joy of Living; Hannover, Sprengel Mus.) exerted a strong counter-influence on Die Brücke’s graphic art. In his paintings such urban subjects as bars and theatre scenes (sketched during Max Reinhardt’s productions at the Deutsches Theater Kammerspiele in Berlin) alternate with brooding seascapes and landscapes. In 1909–13 he completed a series of religious paintings, including the Last Supper (1909; Copenhagen, Stat. Mus. Kst), Pentecost (1909; Berlin, Alte N.G.) and a nine-part polyptych entitled the Life of Christ (1912; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde). At the same time he celebrated the spirit of paganism in a pair of highly charged, Dionysian dance scenes: Dance around the Golden Calf (1910) and Candle Dancers (1912; both Seebüll, Stift. Nolde).

In 1910 Nolde’s Pentecost , which depicts the mask-like faces of Christ and the Apostles crowned by the flame of the Holy Spirit, became the centre of a row that split the Berlin Secession—one of the most advanced exhibiting societies in Germany up until that time, which Nolde had joined in 1908. Nolde’s primitivist treatment of this religious subject, rendered in glowing colours and bold, Expressionist brushwork, found little favour among the older members of the society, who had grown up in the Impressionist school. When Pentecost and the works of most other younger artists were rejected, Nolde attacked the leadership and principles of the Secession in an open letter to its President, Max Liebermann, whereupon he was expelled from the association. Until 1912 he exhibited alongside other rejected artists in the Neue Sezession in Berlin. He also produced woodcuts of religious subjects (e.g. Prophet, 1912; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde; see [not available online]).

2. Interest in primitivism and relationship with the Nazis, 1912–39.

Like most Expressionists, Nolde displayed a growing interest in the art of non-European cultures during this period. In 1911 he had begun to write an introduction to a book on ‘the artistic expression of primitive peoples’, illustrated by crayon and pencil sketches after objects in the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin. Although the book was never published, his sketches were subsequently used for a series of dramatically composed ‘ethnographic’ still-lifes, for example Exotic Figures (Monkeys) (1912; Saarbrücken, Saarland Mus.). Nolde’s enthusiasm for what he imagined to be the pure and childlike qualities of ‘primitive’ peoples, and his admiration for the expressive vitality of non-European art, reached a peak in 1913 when he decided to join an ethnographic and demographic expedition to German New Guinea. His journey overland through Russia, Manchuria, Korea, Japan, China, Manila and the Palau Islands resulted in a series of lively sketches, depicting the people and situations he encountered. In New Guinea he painted large, luminous watercolours of native heads, as well as a series of oil paintings (e.g. Tropical Forest, 1914; Bielefeld, Städt. Ksthalle; and Tropical Forest, 1914; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde; see Landscape painting, colour pl. IV, fig.), some of which were based on small pastel sketches. In 1916 the German Colonial Office bought 50 of Nolde’s watercolours as a demographic record, despite their stylistic boldness and Nolde’s romantic response to the New Guinea peoples.

The South Seas journey, which terminated with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, was a turning-point in Nolde’s art. Coinciding with the end of the heroic years of first-generation Expressionism, it marked the end of the artist’s engagement with modern, urban subjects. Nolde’s objections to colonialism, which he believed detrimental to the pure racial integrity and creative originality of indigenous peoples, confirmed his mistrust in the progress of modern civilization. From this time Nolde drew inspiration more exclusively from the recurrent cycles of nature (e.g. The Sea B, 1930; London, Tate), peopling his paintings with primitivist figures from the Bible, from fables, or from the wells of his imagination.

On his return to Germany, Nolde moved to Utenwarf on the north German mainland and then, in 1927, to Seebüll, where his house, studio and garden were eventually to be transformed into a museum and a centre for the Stiftung Ada-und Emil Nolde, after the artist’s death. During the 1920s Nolde enjoyed general recognition for his art: in 1921 a biography by Max Sauerlandt was published, followed by the first volume of Nolde’s letters in 1927, when the artist’s 60th birthday was also celebrated with a large retrospective exhibition in Dresden. In 1931 Nolde was appointed a member of the Preussische Akademie der Künste, in the same year that the first volume of his four-volume autobiography, Das eigene Leben, appeared.

In 1933 Nolde refused to quit the Akademie der Künste voluntarily, when he was asked to do so by the new conservative factions promoted by the rise of National Socialism. In opposition to party doctrine, the National Socialist student union supported Nolde and nominated him—unsuccessfully—as president of the united art schools. By 1935, however, several of Nolde’s paintings had been removed from exhibition in German museums and 1052 works by Nolde were confiscated in 1937 during the Nazi campaign against ‘degenerate’ art. In the culminating exhibition of Entartete Kunst, which opened in Munich in July, Nolde was prominently represented by 29 paintings and some watercolours and graphic work. During the 1930s Nolde concentrated on such uncontroversial subjects as flowers and landscapes (e.g. Haymaking, 1936; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde). However, he did produce some primitivist figurative works. Nolde’s relationship with the Nazis was complex, since, despite their early attacks on his work, he actually joined the Danish section of the Party in 1933–4. Such shared ideals as the belief in racial purity and the emphasis on forging a strong ‘Germanic’ identity blinded Nolde to the political realities of the movement. Two further volumes of his autobiography, Jahre der Kämpfe (1934) and Welt und Heimat (of which only the first could be published at the time), stress Nolde’s commitment to a revolutionary Germanic art and his belief in racial purity. However, they also contain many artistic and political ideas that fell foul of Nazi ideals. In recounting the Secession affair of 1910, Nolde included certain anti-Semitic statements probably intended to gain favour with the Nazis, which he edited out of the second edition of Jahre der Kämpfe (1958). His recollections of the pre-World War I era are reminders that he had been equally unpopular with both the modernist Secession and the extreme conservatives. It is for this reason that Nolde’s art—more than that of any other German Expressionist artist—remains so important for assessing the complex and contradictory position occupied by the Expressionist avant-garde in the battle between modernists and conservatives in Germany.

3. Later developments, 1940s and after.

Despite his misguided political judgements, Nolde continued to be a victim of the Nazis’ most brutal censorship throughout the war years. In 1940 more paintings were confiscated from his studio and he was forbidden ‘any professional activity …in the field of the creative arts’. It was this order that perversely inspired the most haunting and original work he produced in the second half of his life. His so-called ‘unpainted paintings’, made in secret defiance of the ban imposed by the Nazis in 1941, comprise over 1000 small watercolours depicting visionary and imaginative subjects painted with swathes of jewel-like colours on wet paper (e.g. the Great Gardener, 1940; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde; oil version, 1940).

After the war Nolde spent the last ten years of his life translating the ‘unpainted paintings’ into oil (e.g. Jesus and the Scribes, 1951; Seebüll, Stift. Nolde). Although his work never again reached the heights achieved in these secret watercolours, he enjoyed a final period of recognition and success. In 1947 he completed Reisen—Ächtung—Befreiung, the concluding volume of his autobiography, and witnessed exhibitions in honour of his 80th birthday that took place in Berlin, Kiel, Hamburg and Lübeck. He was awarded several honours and medals, including the award for his graphic work at the Venice Biennale of 1950, and, in 1952, the French order Pour le mérite. After this date he did not leave Seebüll again, where, despite a break in his upper arm, he continued to paint watercolours until 1955.

Jill Lloyd. "Nolde, Emil." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T062679 (accessed April 27, 2012)

Person TypeIndividual

French, 1864 - 1901