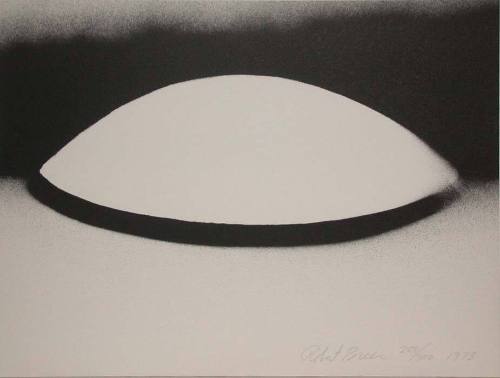

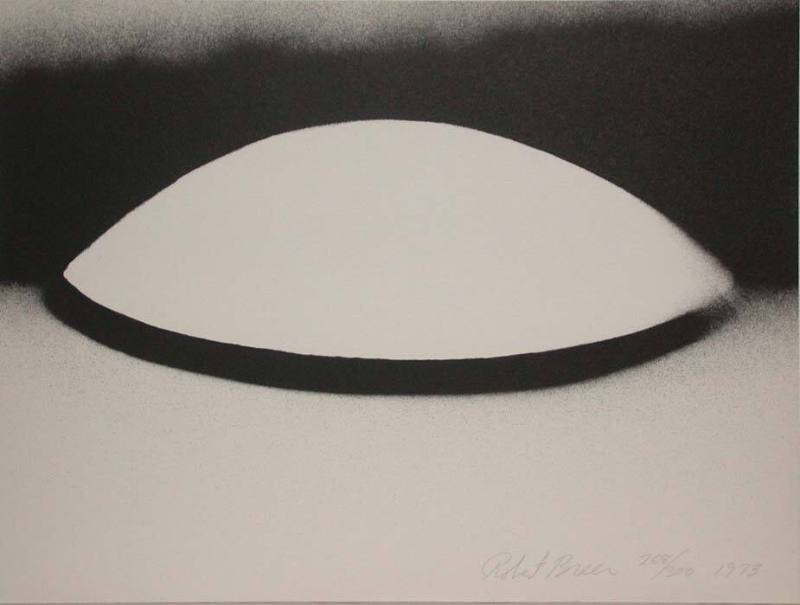

Robert Breer

American, born 1926

Breer has always been fascinated by the mechanics of film. Perhaps his father's fascination with 3-D inspired Breer to tinker with early mechanical cinematic devices. His father was an engineer and designer of the legendary Chrysler Airflow automobile in 1934 and built a 3-D camera to film all the family vacations. After studying engineering at Stanford, Breer changed his focus toward hand-crafted arts and began experimenting with flip books. These animations, done on ordinary 4" by 6" file cards have become the standard for all of Breer's work, even to this day.

Like many of his generation, Breer did early work influenced by the various European modern art movements of the early 20th century, ranging from the abstract forms of the Russian Constructivists and the structuralist formulas of the Bauhaus, to the non-sensible universe of the Dadaists. Through his association with the Denise René Gallery, which specialized in geometric art, he saw the abstract films of such pioneers as Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Walter Ruttman and Fernand Léger. Breer acknowledges his respect for this purist, "cubist" cinema, which uses geometric shapes moving in time and space.

In 1955, he helped organize and exhibited in a show in Paris entitled "Le Mouvement" (The Movement), which paved the way for new cinema aesthetics. During this period, Breer also met the poet Alan Ginsberg and introduced him to his film Recreation (1956), which made use of frame-by-frame experiments in a non-narrative structure. Although Breer disdains being labeled a beatnik, the film does capture some aspects of beat poetry and music.

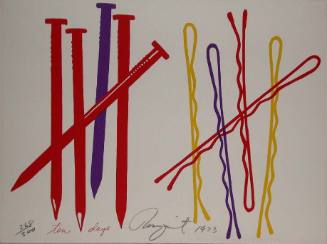

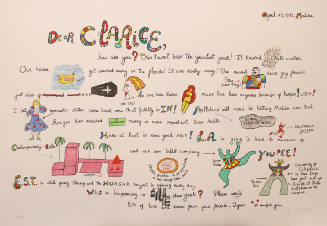

When Breer returned to the United States in the late 1950s, the American avant-garde was thriving and films by Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, Peter Kubelka and Maria Menken were creating a new visionary movement. Breer found kindred spirits within the New York experimental scene. As Pop Art emerged as a phenomenon in the 1960s, Breer befriended Claes Oldenburg and others. He worked on the TV show, David Brinkley's Journal, filming pieces on art shows in Europe; at the same time, he made his debut documentary on the sculptor Jean Tinguely in 1961.

Titled Homage to Tinguely and screened at the Museum of Modern Art, it reflects Breer's interest in mechanical forms and the fine art of moving sculpture; techniques he used in his work, as his own kinetic sculpture was sparked by Tinguely's keen interest in mechanical gadgets, kinetic movement and abstract forms.

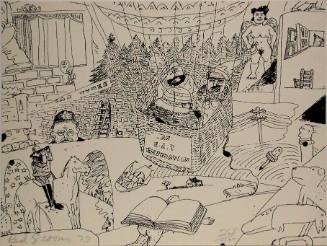

The work, Swiss Army Knife with Rats and Pigeons, Robert Breer, 1981 by Robert Breer is in the collection of the Butler Institute, courtesy of Robert Breer.

Breer was influenced by the new performance art and "happenings", which was making waves in the avant-garde of Europe and New York. He worked briefly with Claes Oldenburg and his performance pieces resulting in a 13 minute film, Pat's Birthday (1962). Breer also befriended artists including Nam June Paik, Charlotte Mormon and others exposed to the new trends in multimedia events.

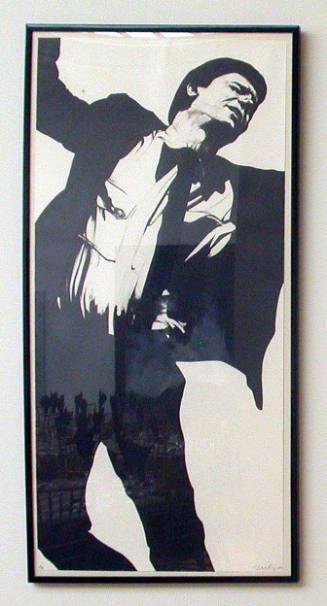

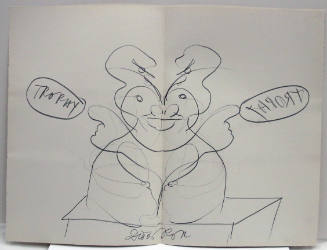

While he was working on the film Fist Fight, he met Stockhausen, then working in Cologne on Originale, a performance piece. The composer's work soon came into vogue in American circles, and he was asked to perform his piece in New York's Judson Hall in 1964. Breer presented Fist Fight as part of this performance, making the film a visual event in its own right.

Always whimsical, Breer soon developed a line technique related to the free-form work of Swiss painter Paul Klee. Such short narrative pieces as A Man with his Dog Out for Air (1958) and Inner and Outer Space (1960) use the dynamics of drawing and line to capture the essence of humor and motion. Time and time again, he relies on the roots of simple techniques of pencils or 4 x 6 cards for inspiration. While Breer rarely uses conventional storytelling techniques, these films have a sense of the quick movements of a Tex Avery cartoon and the wit of an electric comic strip.

Person TypeIndividual