Dan Flavin

American, 1933 - 1996

He served in the meteorological branch of the United States Air Force and then at the National Weather Analysis Center. He participated in four sessions on painting at the Hans Hofmann School in New York in 1956, studied art history at Columbia University, and at the New School for Social Research. His sculpture concentrates on the placement of fittings that produce light within the work. He died in New York in 1996.

Following is an excerpt from "New York Times" online, February 4, 2001:

Dan Flavin: The Last Great Art of the 20th Century, By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

MARFA, Tex. -- THE last great work of 20th-century American art has just been finished in this cattle town, a tumbleweed-tossed speck in the high desert plain near the Mexican border known here as "el despoblado," the uninhabited place, 200 miles southeast of El Paso.

The work is by Dan Flavin, the light artist, who before he died in 1996 left instructions for completing "Untitled (Marfa Project)." It occupies six barracks on a defunct Army base and cavalry post, Fort D. A. Russell, which the artist Donald Judd, during the last 20 years of his life, turned into a kind of Lourdes of Minimalism, a pilgrimage site for devotees of Judd's aesthetically maniacal brand of sculpture.

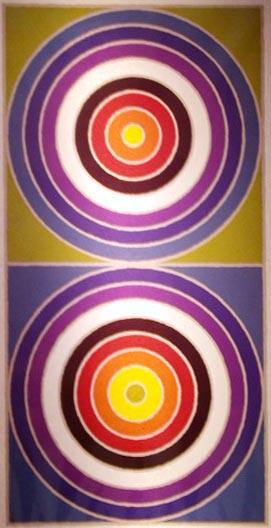

The six barracks sit side by side, 6,000 square feet apiece, jutting into open plain at one end of the fort. At 36,000 square feet total, the work is gigantic, but size isn't its main feature. Inside the barracks, Flavin variously combined his usual colored fluorescent tubes, here erected like bars blocking passage through the buildings. Saturated color articulates these totally spare, elongated, oddly meditative spaces. The century's closing statement about the value of simply standing and looking for its own sake, the work dovetails perfectly with Judd's whole concept for Marfa, an essential addition to High Minimalism's most ambitious and idiosyncratic enterprise.

The six barracks are identical U-shaped buildings, with all their windows covered except two at the long ends of each U. The bottom of the U's are split into parallel tilting hallways, each blocked, either at the front or in the middle, by combinations of pink, green, blue and yellow fluorescent tubes. The tubes are on eight-foot-high, double-sided racks like prison bars set perpendicular to the slanting walls. Natural light coming through the windows is juxtaposed with artificial light inside.

The impact is hypnotic. The art avoids fuzzy mystical-romantic interpretation by virtue of the low, tacky buzz of the industrial tubes, and by the enforced choreography that frustrates one's desire to walk straight through each building.

To see a building complete, you must walk in one end of a barracks, march back outdoors and into the other end. The colors half roadside billboard, half Tiepolo ceiling achieve optical luxury in the same matter-of-fact way that Judd's aluminum boxes do: what you see is what you see, which in Flavin's case has an otherworldly effect, bathing you in subtly mixed luminosity, your interaction with the light and the empty space being the ultimate object of the work, the epitome of Minimalist parsimony and insinuation.

Judd and Flavin hated the term Minimalism, the way all artists hate labels, but also for good reason, because it implied simple- mindedness. The essence of Minimalism, in fact, was concentration, your concentration as viewer, which Flavin's project demands as much as any other work by him. Concentration makes simple things suddenly seem momentous: the exact order of the combinations of colored lights in the barracks; the way yellow light mixed with a lesser amount of blue light makes a kind of white light, but a white light different from natural light; the way fluorescent lights delineate walls, floor and ceiling, the intensity of the contours changing in relation to the distance of the forms from the tubes.

There are few places in the art world where an equivalent stillness exists: not the socially mandated silence of public museums, but a stillness that seems to have physical weight. This alone makes the long trip here worthwhile. You feel it as a presence in Flavin's barracks, with its buzzing colors, deadpan and industrial.

Person TypeIndividual