Hiroshi Sugimoto

American, b. Japan, 1948

Education: Saint Paul's University, Tokyo, B.A., 1970; Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles, B.F.A., 1972. Career: Independent artist, in New York, since 1974. Awards: 2001 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography.

Tokyo-born photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto describes himself as "The Sleepless Photographer." Indeed he is a man who patiently records images which transcend time itself. Sugimoto's images of movie palaces, bodies of water, and architectural structures confound our notions of temporal logic and bring us necessarily into a place of contemplative wonder. Most of his work remains within the context of three extensive series of images: the seascape, the museum diorama, and the interiors of theaters with movies on screen.

Sugimoto began his work in photography in the early 1970s with a strong interest in Minimalist and Conceptual art. Influenced by such artists as Dan Flavin and Carl Andre, Sugimoto began experimenting with ways of expanding the range of the photograph to incorporate temporal shifts often seen in modernist paintings. By the late 1970s, he was producing the first images in the still-growing movie theater series. "The concept was to photograph the entire duration of a movie," Sugimoto said in an interview with Martin Herbert, "so I was imagining that if I were to do that, the result might be a completely white screen.... Usually a photographer sees something and tries to capture it, but in my case I just see it in my head and then the technical process is how to make it happen in the real world. The image, then, is a kind of decoration of the concept." Sugimoto elected to test this idea in the ornate movie palaces from the 1920s and 1930s to give a greater context to the simple white rectangle which results from these movie-length exposures. The theaters he has photographed are mainly in the United States, though he has in recent years done images in Osaka and Milan. Sugimoto has seen great differences in the information gathered from various types of films. "If it's an optimistic story, I usually end up with a bright screen; if it's a sad story, it's a dark screen. Occult movie? Very dark."

This examination of time continued in the diorama photographs done between 1976-80 at New York City's Museum of Natural History. At first glace, the images appear to be documentary shots of animals taken in the wild, creatures in their natural environments. Study of these rich landscapes, replete with creatures engaged in daily struggles for sustenance, revealed subtle hints of artifice. Closer examination shows a strange stiffness in the animals, an all-too-perfect Darwinian posturing. These tableaus are then obvious constructions, situations so lifelike in death that they are startling. Sugimoto captures images here which never existed in "real" time, yet which are presented in museums as virtual snapshots of the actual.

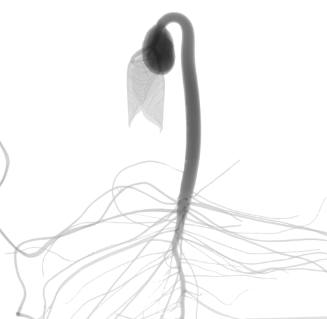

In 1980, Sugimoto began his still-evolving seascapes series. He describes his interest in bodies of water as a way of revealing time. "Ever since the first men and cultures appeared, they have been facing seas and scenes of nature. The landscape has changed over thousands, millions of years, and man has cultivated the ground, built cultures and cities, skyscrapers. The seascapes, I thought, must be the least changed scene, the oldest vision that we can share with ancient peoples." These images require faster exposures, as Sugimoto wants to capture the movement of the waves in his prints. These pictures of the sea have been taken all over the world, and they reveal a contemplative space in which time is at once frozen and yet captured as movement. The interplay of the sky, the smudge of the horizon line, and the ripples on the surface of the water in these images is decidedly meditative and very minimal in design. Most striking is the realization that these are constructions inherent in nature.

While continuing work in images of theaters and seascapes, Sugimoto has moved into other explorations as well. In 1995, he photographed statues in a Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan. The forty-eight part study, Hall of Thirty Three Bays, is another examination of similarity and comparison. "The figures in the temple are all slightly different, so I wanted people's eyes to focus on those differences," he has said. "The [grouped sculptures of a] thousand almost-identical Buddhas which I photographed were made in the 13th century, so that is the conceptual aspect of Japanese art, which was what motivated me to work on it." The temple and the statues are considered national treasures, so Sugimoto had to gain special permission to make images there, a process which took nearly seven years.

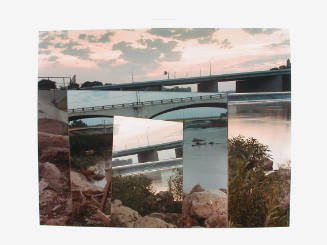

Sugimoto's series of photographs surveying well-known examples of modernist architecture began in 1997, when he was commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles for the project. The concept of time is again central here, as Sugimoto seeks to capture these buildings not as they appear, but as they were imagined in the minds of architects. He photographs them slightly out-of-focus, so that he can "trace back the original vision from the finished product. All the details and all the mistakes disappear; there's a lot of shadows, melting." The result is a soft, impressionistic view of such structures as the Chrysler and Empire State Buildings. They appear more as a dream than as a reality. Sugimoto continues to explore notions of time in his photographs, creating sublime images of things we can't quite see with our own eyes.

Retrieved from http://ic.galegroup.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/ic/bic1/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?displayGroupName=Reference&disableHighlighting=false&prodId=BIC1&action=e&windowstate=normal&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CK1636001560&mode=view&userGroupName=tall85761&jsid=eb2d04a8c3c8c1212c9efc92bfaa825b (Accessed Feb. 16, 2012)

Person TypeIndividual