Georges Rouault

French, 1871 - 1958

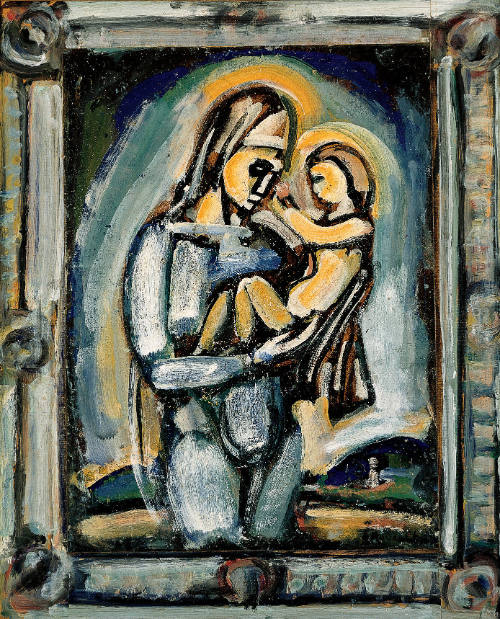

French painter, draughtsman and printmaker. Although he first came to prominence with works displayed in 1905 at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, in the company of paintings by Henri Matisse and other initiators of Fauvism, he established a highly personal and emotive style. His technique and palette were also highly personal, and they ranged from watercolour blues to a rich, thick application of materials. These demonstrate, in their very complexity, not only originality but also the craft of the artist always in search of a greater form of expression. Even though he never stopped observing mankind, his deep religious feeling allowed him to imbue his work with great spirituality.

1. Training and early work, to 1904.

Rouault was born to a humble family during the brief period of the Paris Commune. Through his maternal grandfather, Alexandre Champdavoine, an unassuming post office employee, he discovered artists such as Courbet, Manet and Honoré Daumier at an early age. Having shown a lively interest in drawing at school, at the age of 14 Rouault became a glazier’s apprentice with Tamoni and then with Hirsch, both makers of modern stained-glass windows and restorers of medieval windows, while also taking evening classes at the Ecole des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. His drawings of this period, although academic, already display a concern with direct observation rather than with agreeable effects. His talent was recognized by Albert Besnard, who asked him to execute his designs for stained-glass windows at the Ecole de Pharmacie in Paris, but Rouault declined the offer out of deference to his employer, Hirsch.

On 3 December 1890 Rouault entered the atelier of Elie Delaunay at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris; his fellow pupils included Matisse, Albert Marquet and Henri Charles Manguin as well as Léon Lehmann (1873–1953), René Piot, Paul Louis Baignères and Léon Bonhomme, who became close friends. After painting landscapes influenced not by Impressionism but by great classical painters such as Poussin and Claude, on Delaunay’s death in 1891 he became the pupil of Gustave Moreau. The correspondence initiated in 1893 between Rouault and Moreau reveals the extent to which Moreau became a close friend as well as a great influence and source of encouragement. Rouault learnt from him to treat with scepticism art intended as a mirror of nature, such as Realism and Impressionism. The impact of Moreau’s Symbolism was noted by critics when Rouault was awarded the Prix Chenavard in 1894 for his Infant Jesus among the Doctors (Colmar, Mus. Unterlinden), which he also presented at the Salon des Champs Elysées in 1895. He was passed over for the Prix de Rome in 1896 in favour of a mediocre work by Antoine Larée, an artist who was quickly forgotten. Two years later, Rouault suffered a more real blow with Moreau’s death in 1898.

Moreau left his atelier and collection to the state so that a museum could be established. When it opened in 1903, Rouault became Curator of the Musée Gustave Moreau, in the building formerly occupied by the artist, yet for many years he felt deprived of the spiritual and artistic support of his teacher. Without the haven of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts he wandered around Paris observing the passers-by, opening his eyes to the ordinary human predicaments that were already becoming his principal subject. In 1901 he went briefly on retreat to a Benedictine abbey at Ligugé, near Poitiers, where Joris-Karl Huysmans sought to form a community of artists. As early as 1904 he presented watercolours and drawings of clowns, acrobats and prostitutes at the Salon d’Automne, an annual exhibition in Paris that he had helped establish in 1903, and where he exhibited regularly for many years. These pictures, which broke with the Christian subject-matter of his earlier work, introduced a more introspective approach, but in a profound sense remained truly religious in their compassionate tone and identification with suffering.

2. Themes after 1904: the circus, prostitution and judges.

Georges Rouault: Clown, oil on canvas, 899×683 mm, 1912 (New…In choosing the circus as his theme, Rouault aligned himself with the French painters who preceded him in the late 19th century, such as Manet, Daumier, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec and Degas. Similar subjects were also taken up by other artists of his generation, such as Picasso, Matisse, Léger, Raoul Dufy and Kees van Dongen. Rouault’s highly personal approach, comparable to that of Baudelaire in a poem written in 1861, ‘Le Vieux Saltimbanque’, involved not the outward signs of make-up, powder and sparkle but the life hidden behind them. For him the clown symbolized the function of laughter in overcoming one’s own sense of suffering; see Clown, 1912. Seeing the clown and circus performer as a kind of Christ figure, he pictured him or her almost without exception not on stage (e.g. The Circus, Basle, Kstmus.) but either before or after his or her public appearance, as in Horsewoman (1906; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris).

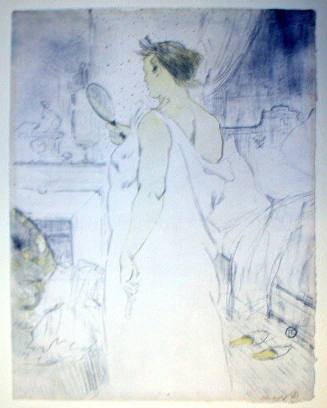

Another subject that Rouault took up at this time, in 1903, was that of prostitution. One of his first treatments of such imagery, the triptych Prostitutes (1905; one panel, Mr and Mrs Poulot, France, Philippe Leclerq priv. col., see Courthion, p. 125; other two panels, Prostitute and Terpsichore, both untraced), was inspired by the novel La Femme pauvre (1897) by the French Catholic writer Léon Bloy, whom he met in 1904; this picture was one of the group of iridescent and brilliantly coloured paintings shown by him at the Salon d’Automne in 1905 alongside works by Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck and others, leading to his temporary and misleading identification with Fauvism. Rouault found in Bloy’s writing confirmation of his need for justice and a deep-seated, secret revulsion for a certain established order. The treatment of brothel scenes by 19th-century artists such as Constantin Guys, Degas and particularly Toulouse-Lautrec had stressed the modernity of the subject and sometimes its shock value in defiance of bourgeois codes of conduct. Rouault’s intentions, by contrast, resided essentially in a compassionate identification with these women, unattractive and destitute, in whose gaze he saw only an infinite sadness, the deep weariness of those who have given up struggling against their own degradation. His prostitutes, represented without irony or criticism, are shown to be vulnerable and fragile, like the circus girls they often resemble. Although his treatment of this theme provided him with some of his greatest masterpieces, after 1914 he returned to it only on rare occasions.

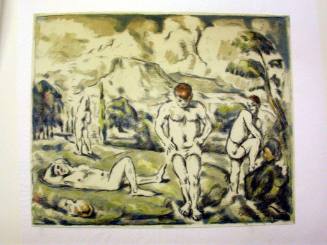

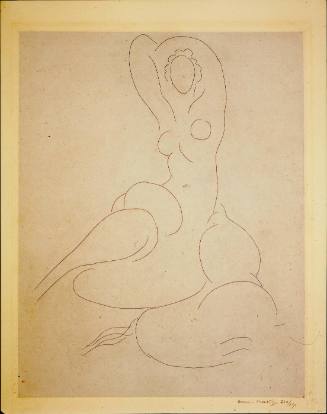

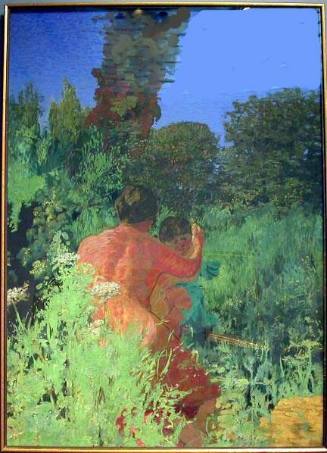

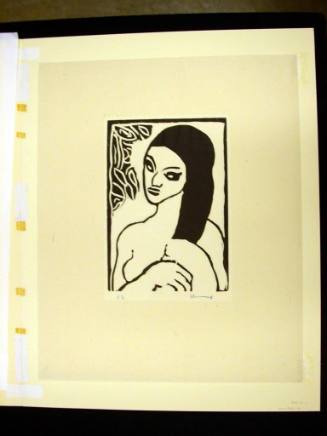

From 1902 to 1914 Rouault also painted nudes and figure compositions with an expressive force, but with the emphasis on purely pictorial concerns rather than with social, humanitarian or Christian issues. His admiration for Cézanne’s Bathers and for his handling of watercolour is evident in these works, with their consciousness of outline, shape and pure arabesque; like Cézanne he also made use of unpainted space to intensify contrast and of colour to seize form. He continued to paint nudes, not just for formal reasons but as a way of glorifying the gracefulness and beauty of the female body.

In 1907, Rouault met the dealer Ambroise Vollard through the studio of André Methey and first sold works to him. The following year he married Marthe Le Sidaner (sister of the painter Henri Le Sidaner). He had just begun a new series concerning judges and the courts, mostly in the form of oil paintings. The first work in this series, the Condemned Man (1907; priv. col., see Courthion, p. 87), was inspired by cases at the Court of the Seine attended by him for almost a year with his friend Granier, the deputy public prosecutor. Although he maintained that he liked the colour contrast of black cap and red gown, his fundamental concern in these works was with the idea of justice, with the drama of the situation and its Christian implications. The men and women depicted in these pictures, sometimes verging on caricature, are not marked by any particular period but are powerful and eternal symbols of human affliction. Rouault hardly touched on this theme after 1914, with the exception of a few heads of judges towards the end of his life.

The emergence of Rouault’s distinctive style, evident in one-man shows held in 1910 and 1911 at the Galerie Druet in Paris, brought with it criticism of his tendency towards the ugly, wretched and shameful. Although he painted his first landscapes in 1910, for example Landscape (The Barge) (1910–12; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris), he continued to address himself primarily to the human form. In figure studies that he himself referred to as ‘grotesques’, he depicted unskilled workers and tradesmen at the very moment when their livelihood was beginning to be threatened by industry. While working from 1907 to 1914 on a moving series, the Faubourg of Toil and Suffering (Depressed Suburban Areas), in which he broached this theme of wretchedness, he began using a distemper technique whose opacity and density foreshadowed the progessively thicker impastos of his last 20 years. In eliminating the slight shine of the oil medium, it was as if he had rejected even the smallest tricks to evoke the mood he sought.

Rouault presented vagabonds, manual workers, fugitives and destitute mothers as Christlike heroes redeeming the sins of others through their suffering. On the other hand, in works such as Mister X (1911; Buffalo, NY, Albright–Knox A.G.) he readily expressed his disgust for all those mostly bourgeois people, who, big and fat, swollen with pride and stupidity, successful and well dressed, were no more concerned for their bodies than for their souls. He also gently mocked professional conference debaters and pedagogues, whose practice of talking, affirming and defining can be so harmful when wrong. The anti-German flavour of some of these works, begun during World War I, was balanced by the sympathy he expressed for the suffering of others, for example the Wandering Jew (wash drawing, 1918; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris).

3. Development of mature style, 1913–30.

Vollard’s purchase in 1913 of Rouault’s complete studio and his appointment in 1917 as Rouault’s exclusive agent marked the start of a collaboration that ended only with Vollard’s death in 1939. The arrangement brought Rouault financial security and reinforced his belief in the artistic value of his work. From this time he achieved a more balanced structure in his paintings and a more harmonious relationship of the zones of colour. In 1917 he was asked by Vollard to illustrate a text he had written about Alfred Jarry’s character, Père Ubu. André Derain and Jean-Louis Forain had already rejected the commission, but Rouault accepted on condition that he would be completely free in his illustrations and that he would then be able to make the engravings for Miserere, a meditation on death, which he had conceived in 1912. Vollard was instantly charmed by his first illustration (see Dorival, 1988, pp. 58 and 62) for the series, an image of a black man, apparently based on visits made by Rouault to a black revue staged in Paris. For Rouault this provided another opportunity to study a victim of society, the black slave, as well as the role played by class and race in human relations. He worked on Vollard’s Les Réincarnations du père Ubu (Paris, 1932), with its 22 etchings plus 144 wood engravings by Georges Aubert after Rouault, for more than a decade, but won instant acclaim for it on its appearance in spite of the weakness of Vollard’s text.

Vollard funded the printing project, Miserere, after the outbreak of World War I. The artist’s original intention was to include 50 plates concerning the Miserere and a further 50 on the theme of war, but in its final form, as published in 1927 by Jacquemin, it consists of only 58 plates printed in black . As with the Ubu illustrations, the prints were preceded by studies in the form of wash drawings and sometimes even by oil paintings transferred to the metal plates by photogravure and then so heavily reworked by the artist that almost no trace of this first image remains. Rouault had hoped to commission accompanying texts from his friend the French essayist André Suarès (1868–1948), who had just returned exhausted from exile, but in the end created his own captions for each plate, using common expressions or phrases from the Bible. With a cast of characters drawn from the types that had long preoccupied him—the poor man, the rich man, the judge, the condemned man, the bourgeois, the clown and Christ—Miserere is in perfect spiritual concord with the painted works, from which it is inseparable.

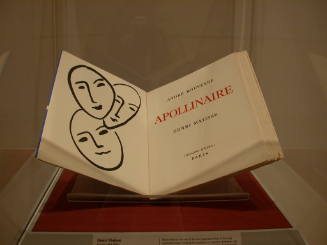

Rouault enjoyed more immediate success internationally with his prints than with his paintings; for example, he was accorded an exhibition of his prints at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1938, although it was only in 1945 that a comprehensive collection of his works was presented there. After producing an illustrated edition of Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal (Paris, 1927), in 1930 he turned to coloured etchings, in which he achieved chromatic effects similar to his paintings. Vollard published Cirque de l’étoile filante (17 etchings and 82 wood engravings; Paris, 1938), both written and illustrated by Rouault, followed by Passion (17 etchings and 82 wood-engravings; Paris, 1939), accompanying a text by André Suarès. Among the other projects that slowed down Rouault’s production as a painter between 1918 and 1930 were stage sets for a production by Serge Diaghilev of Sergey Prokofiev’s ballet L’Enfant prodigue (June 1929) and books illustrated with lithographs, notably his autobiography Souvenirs intimes (Paris, 1926), with six tipped-in lithographs, and Paysages légendaires (six tipped-in lithographs and reproductions of fifty drawings; Paris, 1929). Far from hindering his development as a painter, however, the pleasure of reworking a subject that he exploited in his prints showed itself increasingly in his paintings after 1930, in the encrustation of materials as an important structural element. This working method of revisions and improvements, with a dense layering of colour, distracted Rouault from his initial savagery, whether religious or social. If his sketches were sometimes an indictment of what he saw, this was no longer the case with his finished paintings.

4. Work and reputation after 1930.

Having already mastered his style and broached the principal themes of his work, after 1930 Rouault concentrated on achieving the greatest expressive force through technique, particularly through the free use of colour. Returning to landscapes, for which he consistently took as a point of departure motifs he had sketched before 1916, his search for what he called ‘true tone’ made him one of the great colourists of his generation. Through landscapes he found the serenity he needed to achieve harmony in his composition, arrangement of planes and distribution of keynotes of colour. After 1932 he developed a new landscape style, generally of sunset scenes with Christ or other static figures on seemingly deserted soil beneath a sky blazing with light, for example Christ and Fishermen (1937; Paris, Mus. A. Mod. Ville Paris). During this period he painted many other religious scenes, including Head of Christ (1937–8; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) and Christ Mocked by Soldiers (1932; New York, MOMA).

Rouault’s reputation as one of the great modern artists was established dramatically with a room devoted to his work up to 1918 at an exhibition, Maîtres de l’art indépendant, organized by Raymond Escholier at the Musée du Petit Palais in Paris during the Exposition Internationale des Artes et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in 1937. This was followed by important exhibitions in the USA, beginning with a one-man show at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, in November 1937, continuing with an exhibition of his prints in 1938 (New York, MOMA) and culminating in 1940 with the publication of a monograph by Lionello Venturi and retrospective exhibitions in Boston, Washington, DC, and San Francisco.

Rouault’s style changed after 1940. Using an even thicker consistency of encrusted paint, he treated colour as light in order to give the painting a spirituality augmented by the hieratic nature of the figures, the simplification of shapes and the deliberately false perspective. Although his subject-matter included pierrots and still-lifes, for example of flowers surrounded by a decorative motif, he occasionally reacted very forcefully to human savagery, notably in a painting begun during World War II, Homo Homini Lupus (Hanged Man; 1944–8; Paris, Pompidou).

Lengthy litigation between Rouault and Vollard’s heirs following the dealer’s death in 1939 was finally resolved by a lawsuit brought by the artist in 1947. Winning an order that the 315 paintings they were holding, which he considered unfinished, be returned to him, he burnt them all in the presence of a bailiff, aware that he could not finish them.

The Catholic church, which had been unable to understand Rouault’s work or to recognize its spirituality, came to terms with his art after World War II. Five windows commissioned for Assy church were completed in 1949, and in 1951, on his 80th birthday, the Centre des Intellectuels Catholiques arranged a homage in his honour at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris; on this occasion the Abbé Maurice Morel, the writer of more than one text on Rouault’s work, presented the first version of his film on Miserere. In 1953 Pope Pius XII sent Rouault an honorary decoration, and at the service following the artist’s state funeral an address was delivered by Abbé Morel at the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. After his death the profound and sincere spirituality of Rouault’s art was at last fully acknowledged.

Danielle Molinari. "Rouault, Georges." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074150 (accessed March 7, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

French, 1864 - 1901