Pablo Picasso

Spanish, 1881 - 1973

While Picasso's biography covers a long period of time, the facts are relatively simple. Apart from a few journeys, many homes and some close female companions, his life was entirely taken up with the creation of his enormous quantity of work. At the time of Picasso's birth, his father, an academic painter, taught art at the Escuela de Artes y Oficios in Málaga and was an art restorer at the local museum. In 1891 the family were in La Coruña, where his father taught at the college and Pablo took lessons at the Da Guarda Art School. Encouraging his son's precocious talent, Picasso's father passed on his academic knowledge and at about the age of 12 Pablo painted his first canvases, which he signed: Pablo Ruiz. In 1895, when Picasso was 14, the family moved to Barcelona and he entered the Escuela de Bellas Artes de la Lonja. During the winter of 1897-1898 he attended the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. Back in Barcelona in 1899 he was a regular at Els Quatre Gats, a café popular with intellectual and artistic youth.

On his first trip to Paris in 1900, where he caught up with his friend, the painter Isidro Nonell, Picasso barely associated with anyone outside the Spanish community. Nonetheless, Berthe Weill bought one of his paintings and in 1901 Ambroise Vollard held an exhibition of his racecourse and bar scenes. From then on he signed his works with his mother's surname Picasso. At the end of 1901 he returned to Spain, only to go back to Paris at the end of 1902. He left for Spain at the beginning of 1903 and remained there for a year. When he then returned to Paris, he set himself up in one of the studios in the wooden house at number 13 in the old Rue Ravignon, nicknamed the 'Maison du Trappeur' (The Trapper's House) and later renamed the 'Bateau-Lavoir' (Washhouse) by Apollinaire. For several years he lived there with Fernande Olivier who often modelled for him and who also began to paint. At that time Montmartre was the hub of the arts and attracted people from all over the world. It was there that Picasso met Max Jacob and later Van Dongen, André Salmon and Apollinaire, as well as Matisse in 1906, and Derain and Braque in 1907. It was in Picasso's studio that he and his friends mischievously but affectionately organized a banquet in honour of the Douanier Rousseau in 1908. After Picasso sold his first works to the Russian art collector Sergei Shchukin in 1908-1909, he could put the years of great material difficulty behind him. His so-called 'Blue', 'Rose' and 'Negro' periods ended with the development of Analytical Cubism, which was to preoccupy him from 1910 until war broke out in 1914. He stayed in Cadaqués with Derain and in Céret with Braque in 1910, with Gris in 1911 and in Sorgues (Vaucluse) with Braque in 1912. The young art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler secured exclusive rights to Picasso's works in 1912. After 1912 Picasso and everyone who painted or wrote in Montmartre migrated to Montparnasse. With the outbreak of war, however, the community disintegrated, as many either died or were dragged away from their art for the next several years.

When war broke out in 1914 Picasso was in Avignon. He travelled to Italy in 1917 and associated with Cocteau, Diaghilev, Massine, Stravinsky and Satie in Rome. Standing in for the absent poet-turned-soldier Apollinaire, Serge Diaghilev, another conjuror of ideas and projects and director of the Ballets Russes, commissioned sets and costumes from Picasso for the ballet Parade written by Jean Cocteau and with music by Éric Satie. Picasso fell in love with the dancer Olga Kokhlova, whom he married in 1918, and they had a son. The marriage broke up in 1934 although they never divorced. The performance of the ballet in Paris caused quite a stir. In 1917 Askionov's book on Picasso was published in Moscow. From 1919 to 1924 he created more sets, costumes and curtains for productions of Manuel de Falla's The Three-cornered Hat (El Sombrero de Tres Picos) and Stravinsky's Pulcinella by the Ballets Russes. The period from 1928 to 1929 when he was living in Dinard became known as the 'Dinard' period. In 1933 and 1934 he paid two lengthy visits to Spain, after which the Minotaur theme started to develop. At the beginning of the 1930s his personal life inspired a large number of portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Following the outbreak of Civil War in Spain in 1936, the subsequent nationalist victory and the Franco era, Picasso never again returned to Spain. During this period dominated by the creation of Guernica, he lived with Dora Maar in Paris. He was living in Royan in 1939 at the outbreak of World War II but spent the years from 1940 to 1944, the entire period of German occupation, in Spain.

After the war, Picasso settled in the south of France. Unless they appeared in his work, the names of his companions are unimportant, apart from Françoise Gilot, by whom he had two children. For several months in 1946 he worked in the rooms of the Château Grimaldi, which was later to become the first Musée Picasso, largely due to the significant donation he left after his departure. For several years after 1948 he was mainly active in Vallauris where, through his own work and dynamic presence, he renovated the local ceramic craft industry. In 1953 he separated from Françoise Gilot and in 1955 moved to Cannes, where he lived in the villa 'La Californie' and bought the Château de Vauvenargues in 1958. His wife Olga Kokhlova had died in 1955 and he married again in 1958. His new wife was Jacqueline Roque whom he had met in 1954. The couple settled in Mas Notre-Dames-de-Vie in Mougins in 1961. He spent his remaining years in Mougins, painting several canvases a day until his death in 1973 at the age of 92.

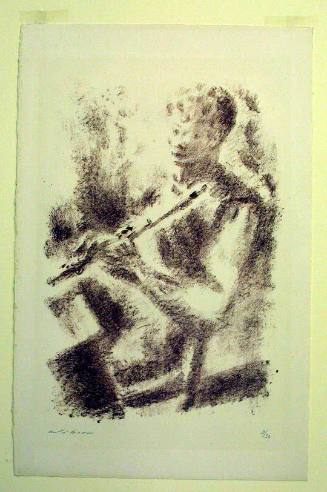

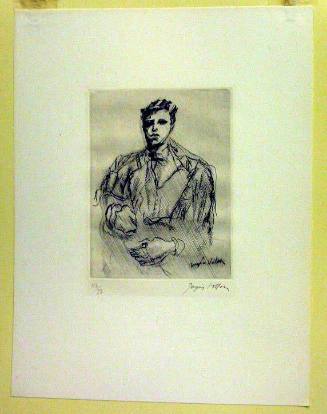

While painting constitutes the major part of his work, the quantity of drawings, engravings and sculptures is also impressive, all the more so as they reveal the same abundance of creative genius. Thousands of drawings and brush washes (said to be around 20,000) accompanied the progress of his work throughout his career, and often series of them ran parallel to series of paintings. From 1904 to 1905 Picasso engraved a series of etchings and dry-points, corresponding to his Rose period, of which the 14 copper plates were bought by Ambroise Vollard who published them in 1913 under the title Acrobats (Saltimbanques). Throughout his life he produced a considerable quantity of individual engravings, which can only be dealt with in specialist catalogues, such as Bernard Geiser and Brigitte Baer's Picasso: Painter-Engraver. Catalogue Raisonné of Engravings, Lithographs and Monotypes, but mention should be made of the Minotauromachy of 1935, the Sueño y Mentira de Franco series, and the Vollard Series (Suite Vollard) of 1937.

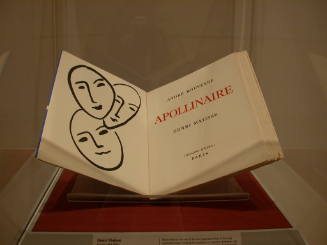

With regard to his work as an illustrator of literary works and the albums he designed, Patrick Cramer in his catalogue and Luc Monod in his manual list more than 100 works either illustrated by Picasso or to which he contributed illustrations, including: Poems (Poèmes) by André Salmon (1905); Alcohols (Alcools) by Apollinaire (1908); the four etchings (corresponding to his Analytical Cubist period) in Max Jacob's St-Matorel (1911); Max Jacob's Siege of Jerusalem (Le Siège de Jérusalem) (1914); Max Jacob's The Dice Cup (Le Cornet à Dés) (1917); Apollinaire's Calligrammes (1918); André Salmon's The Manuscript Found in a Hat (Le Manuscrit Trouvé dans un Chapeau) (1919); Pierre Reverdy's Hangman's Ropes (Cravates de Chanvre) (1922); André Billy's The Life of Apollinaire (Apollinaire Vivant) (1922); 30 'Classical' etchings for Ovid's Metamorphoses (1931); 13 etchings and woodcuts (corresponding to his Neo-Classical period) for Balzac's The Unknown Masterpiece (Le Chef-d'oeuvre Inconnu) (1932); Aristophanes' Lysistrata (1934); Paul Éluard's The Safety Rail (La Barre d'Appui) (1936); Paul Éluard's Fertile Eyes (Les Yeux Fertiles) (1936); Buffon's Natural History (Histoire Naturelle) (1942); Georges Hugnet's Honeysuckle (La Chèvre-feuille) (1943); Robert Desnos' Contrée (1944); Paul Éluard's To Pablo Picasso (À Pablo Picasso) (1944); Apollinaire's The Breasts of Tiresias (Les Mamelles de Tirésias) (1946); Ramón Reventos' Two Tales; Góngora's Twenty Poems (1948); Iliazd's Escrito (1948); Pierre Reverdy's Song of the Dead (Le Chant des Morts) (1948); Mérimée's Carmen (1949); Aimé Césaire's Lost Body (Corps Perdu) (1950); Tristan Tzara's In Living Memory (De Mémoire d'Homme) (1950); Paul Éluard's The Face of Peace (Le Visage de la Paix) (1951); Diderot's Mystification (1954); Picasso's own Poems and Lithographs (Poèmes et Lithographies) (1954); Tristan Tzara's À Haute Flamme (1955); Roch Grey's Midnight Horses (Chevaux de Minuit) (1956); Max Jacob's Chronical of Heroic Times (Chronique des Temps Héroïques) (1956); Magry y Jiménez de La Espada's The Mendicant Friar (1959); Pablo Neruda's Toros (1960); Pidare's VIIIe Pythique (1960); Jean Cocteau's Picasso (1962); Miguel Dominguin's Toros y Toreros (1962); Douglas Cooper's Les Déjeuners (1962); Fernand Mourlot's Picasso the Lithographer (Picasso Lithographe) (1964); Pierre Reverdy's Quicksand (Sable Mouvant) (1966); Douglas Cooper's Theatre (1967); and Fernando de Rojas' La Celestina (1971).

The work of Picasso the sculptor is equally rich, comprising more than 350 works, not counting the ceramics. Besides the movable sculptures, some monumental works were made from his models, notably a metal sculpture for Chicago Civic Center, as well as others in cement and crushed granite, such as the 26 feet (8 metre) high Sylvette for the Bowcentrum in Rotterdam. Reference should be made to catalogues, particularly Werner Spies and Christine Piot's Das Plastiche Werk: Werkverzeichnis der Skulpturen. Although he started sculpting as an adolescent, the only sculpture from this early period to be kept was Seated Woman (1902), which, like Madman and Harlequin (1905), still shows Rodin's influence, whereas the Blind Singer (1903) and Woman's Head (1906) break free from his influence. In 1906-1907 the relief mask Woman's Head was similar in its Primitivism to Picasso's pictures of Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon. Later on, Picasso's sculpture would often be quite separate from his painting. The three Figures (1907), kind of wooden totem poles, summarily cut and gaudily coloured in red and white, and perhaps also the large and rustic Woman's Head (1909-1910), still belong to the period of primitive inspiration. With the various trimmings and real objects, the painted cardboard reliefs, such as Violins (1913-1914), Still-life, and Glass of Absinthe (1914), together with the contemporary collages, freely but logically accompany Picasso's paintings from the Analytical Cubism period. Several copies of the Glass of Absinthe, assembled partly in wax, with a real spoon, were cast in bronze, each then being painted in different colours. Picasso did not sculpt again until the four Metal Constructions of 1928-1929, when he assisted Julio González, who introduced him to working in metal and soldering. After that he continued to use this assemblage technique, but often softening it by using real objects completely diverted from their function, as in Woman's Head (1931) made up of iron colanders painted white.

Over the next decade or so his sculptural output appeared in very different ways and with no obvious link to the paintings of the same period. Women (1931) is wooden and spindly, recalling Giacometti's work. Other assemblages are almost precious, such as Matchsticks, Drawing Pins, Blades of Grass, Butterfly (1932), the bronze Rooster (Coq) (1932), the strange figures in high relief, contorted and grotesque (1934), a very graceful and noble Head of a Young Girl (1941), the Skulls (1943), and the apocalyptic Rooster (Coq) (1943). Also in 1943 he created what is undoubtedly the height of his assemblage work, the Head of a Bull, also known as the Saddle and Handlebars, stemming from the supposedly chance association (in so far as it is devoid of any artistic device) of a bicycle saddle and handlebars. He then frequently pursued this technique of assembling salvaged eclectic items, as in the 1943 work in which a vase, a branch and a biscuit tin, among other things, make up the Woman with an Apple. During the same period, in 1944, with the Man with Sheep, Picasso revived a tradition that, if not Classical, was at least newly derived from Rodin. The Man with Sheep was later cast in bronze for a commission from the town council in Vallauris, where Picasso was living at the time. His bottle-women, head-vases and owls revived the local pottery craft. Then followed some larger sculptures: Goat, just one copy of which was cast in bronze in 1952, 'constructed' from a basket with a hole in it shaping the sides, a board with nails in it, a paddle arching the spine, ribs of palms, earthenware jars, a tin can, and a length of barbed wire all assembled with plaster (1950); Little Girl Skipping and Woman with a Pram (or Pushchair) (1950); and later the Female Monkey and its Young (1952-1955). In the sculptural work can also be included the equally considerable output of Vallauris ceramics, for which reference should be made to Georges Ramié's Picasso the Ceramist (Picasso Céramiste). Sometimes a work designed in ceramic, such as the 1948 Centaur, was eventually cast in bronze. After 1960 Picasso returned to techniques corresponding to the old cardboard reliefs and soldered metal sculptures, cutting or (apparently) simply tearing paper or cutting, folding and painting sheet metal to make comical figures, such as Woman and Child (1961).

As far as painting is concerned there is very little to say about Picasso's works as a young schoolboy, except his obvious talent, his serious training and an already enormous capacity for work as well as technical mastery in a classical sense. This latter was recognised as early as 1897 when at the age of 16 he was awarded a distinction at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid, followed by a gold medal at the regional exhibition in Málaga, for his painting Science and Charity (Ciencia y Caridad). In Barcelona in 1899 he began to free himself from his academic training, influenced initially by his admiration of El Greco and Goya, and later Manet, Van Gogh and Gaugin. The period between 1900 and 1903, when Picasso alternated between Paris and Barcelona, corresponds with the Blue period in his paintings, marked by his recent discovery of Degas, Vuillard and Toulouse-Lautrec. The Rose period dates from 1904 to 1906, during Picasso's early years in Paris. No doubt he saw the future in lighter colours. The old beggars and sickly children from the dusk of the Blue period give way to a dawn of young acrobats in Harlequin costumes and little girls on the verge of womanhood.

The beginning of the Negro period dates from the end of the Rose period and, although Picasso denied it, correponds with contact with the first African masks acquired by Derain. In 1907, after numerous preliminary studies, 17 of which were required for the single final composition, Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, in which it is generally claimed that the foundations of Cubism can be seen, but this view is only partially sustainable. The brothel theme has only anecdotal significance, in so far as it is present only in the sketches. The distortions of the female body and the arbitrary colours are more similar to the German Expressionists of the Brücke. Innovation is seen largely in the multiplied fragmentation of the bodies viewed simultaneously from different angles. It was only in 1908 that Cezanne's Houses in Estaque (Maisons à l'Estaque) (and in 1909 Braque's landscapes of La Roche-Guyon) provoked the critics' eloquent, ironic remarks about the 'cubes' to which the initial aspect of the buildings in these two series of landscapes had been geometrically reduced. After Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the figures and still-lifes painted by Picasso still referred to Cézannist geometrisation of volumes and the vertical inversion of depth, until the Horta del Ebro landscapes, which he did not paint until 1909 although he had known the village since 1897, and in which Braque's former cubes can be seen. Like Braque, the years known as Picasso's Negro period were essentially dominated by the influence of Cézanne, apart from certain variations after Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, such as Harlequin Family (1908), the geometrisation of which was a forerunner of the Cubist period proper.

It was only after 1910 that both Picasso and Braque brought their experiments to their ultimate conclusion, the 'Analytical' period of Cubism. The depth of painting was reduced to that of a low relief; colour was reduced to the minimum of greys and ochres. The synthesising geometrisation of forms culminated in the almost total suppression of their recognisable identity, while the break-up of these forms completed their de-identification and is generalised, as if seen through a many-sided glass prism, in which simultaneous time-lags reassemble the multiplicity of view points in a single figure. Analytical Cubism concentrates the painting on the constituent factors, to the exclusion of extraneous elements which do not really belong to it, in an expression which means nothing other than itself, in the same way as music. This isolation of just the formal values denies any significance to the original subject other than a pretext for variations to exalt the act of painting itself and its own means; format, lines and the surfaces they engender, the tones which fill them with their variations, and the infinite complexity of all the possible combinations of these elements.

It was during the Analytical Cubism years that the full flowering of Cubism was reached and, as well as Picasso and Braque, various other people came together with the same aesthetic ideas, but this time a little more clearly standardised. Still-life particularly lent itself to this game of equivalence, this transubstantiation of real facts into formal facts. Picasso, however, did not hesitate to move on to applying this prismatic vision to portraits, as in his Portrait of Ambroise Vollard and Portrait of D. H. Kahnweiler (1910). From the years 1911-1913 Picasso moved away from the austere monochrome of the Analytical period, notably in the series of still-lifes My Pretty (Ma Jolie) of the short so-called 'Rococo' period, in which he reintroduced bright colours into speckled planes or even blocks.

In Sorgues in 1912, the first papiers collés (paper collages) were created at the instigation of Braque. This involved the introduction of printed letters, words and figures from documents, newspapers, wallpaper, tobacco packets, imitation wood or real objects into the painting (then at the limit of Non-Representation), transferring them onto it and conferring on it a status of objectivity. Painting, playing the small part that it did, became an object in its own right and took on a value equal to that of the real element integrated within it. This integration of real elements into the picture is sometimes thought of as a refusal to allow Analytical Cubism to drift towards total Abstraction. In 1913-1914, extending the process of integrating real elements into the work, Picasso made his first sculpture-assemblages, which at that time were Cubist, and went on to adapt this new technique to the various periods of his subsequent development.

Declaration of war in 1914 caused the break-up of the newly created artistic community at the École de Paris, and in particular the Cubist group, leaving Picasso isolated. No longer able to share in the spirituality of the Analytical Cubist community, Picasso, whose ascetic discipline was fundamentally at odds with the exuberance of his Spanish origins, progressively freed himself from Cubism during the so-called 'Synthetic Cubism' period, only retaining certain stylistic elements of Cubism which were more and more diverted towards Expressionist ends. To this same end he reintegrated colour into his works, this time almost for good. The expression 'Synthetic Cubism' has given rise to various interpretations. It may seem hardly applicable to just Picasso and, as far as he was concerned, it ought only to be understood as abandoning strict analysis in favour of an attitude that encompasses a total synthesis of certain elements of original Cubism with a greater thematic and stylistic freedom. Reclaiming total freedom was merely a prelude to the alternation of sometimes disparate and often badly defined periods, which, overlapping and reappearing in turn, would produce the vast quantity of Picasso's work that was to follow. In 1915-1916 he even painted a few naturalist pictures, particularly portraits of friends, such as Satie, Stravinsky and André Breton. In 1917, when he was assisting with the ballet Parade, certain elements of his sets and particlarly the main theatre curtains show a clear return to Realism, advocated moreover by Apollinaire in the programme which took up the ideas of the manifesto New Spirit (Esprit Nouveau), in which the word 'Surrealism' appeared for the first time.

After this came what is known as the 'Antique', 'Neo-Classical' or even 'Ingresque' period, which lasted into the 1920s when Picasso painted large nudes inspired by Roman statues that he had seen on his trip to Italy, and a number of pictures of Mother and Child (Maternités) following the birth of his son. However, at Fontainebleau in 1921 he painted two of his most important Cubist works, the Three Musicians (clearly inspired by an earlier work by Hayden) and the Three Masks. In 1923, while painting a series of Harlequins that were still very Realist after he discovered the Italian Renaissance when he was in Italy, Picasso started the series of large still-lifes which were exhibited in 1926 at Paul Rosenberg's gallery and which are like infinitely free and joyful variations on the themes of the new Cubists. From 1925 to 1932, and especially during the Dinard period in 1928-1929 when he was associating with the Surrealists (to whom he was more attached than to their principles), there followed several works of applied Surrealism. These were mostly female figures, with monstrous and unhealthy anatomical distortions, through which he is believed to have expressed his disaffection for his wife Olga or rather his erotic obsessions and personal anguish, in which, at that time at least, there was a latent if not overt sadistic dimension. In the years that followed, the series of portraits of Marie-Thérèse Walter show women in a pleasant light again, their gentleness rediscovered.

In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques opened in Paris. For the Spanish pavilion, still created and managed at that time by the Republic, Picasso painted the immense composition Guernica in the style of a fresco, treated graphically and starkly set off by pale greys and ochres. The intention was to portray the way the Spanish people had been torn into two opposing factions, and to accuse the Francoist Party of Fascist behaviour and collusion with the Nazi government. The painting was inspired by the bombing of the small Basque port of Guernica by Stukas, new German planes that were carrying out tests in preparation for the next war. In the same deflagration, an impassive and dominating Minotaur with human eyes, screaming women brandishing their murdered children, and broken horses tensed in their last breath are tangled together under the naked bulb of misery. Picasso was always opposed to Guernica being shown in Spain until it had returned to democratic government; deposited in the New York Museum of Modern Art, it did not reach Spain until 1980, five years after the death of Franco.

During this period, which does not seem to have been given a particular classification, but which could be called Cubo-Expressionist, Guernica was not an isolated work. Besides the many preliminary studies of details of the final composition, other paintings are connected with this expressive, dislocated representation, such as Weeping Woman (La Femme qui Pleure), Little Girl with a Lollipop (La Petite Fille à la Sucette), and Seated Women (Les Femmes Assises). In addition to the movingly graceful portraits known to be of her, Dora Maar was the model for many other figures subjected to maximum deformation, some typically Cubo-Expressionist, echoing the Spanish Civil War and presaging the imminent World War. The 1939 Night Fishing in Antibes, a composition as formally ambitious as Guernica although in a smaller format and in a totally different style, seems like a nostalgic witness of threatened happiness. Then, the series of still-lifes exhibited at the Galerie Louis Carré in 1945 could easily be grouped together into a 'White' period, although it is not called that. This series corresponds both to a mastery of harmoniously intertwining lines and the equilibrium of masses, diversified by the treatment of the material, keeping colour at the same time as symbolic anguish in themes that are funereal or taken from sordid reality: Still-life with Ox Skull (1942) and Pitcher and Skeleton (1945).

After the war, having settled in the south of France where he created ceramics in Vallauris, Picasso painted in the then disused Musée d'Antibes. He offered the museum all the works he had painted based on the legends of Greek sailors who had come to the western shores of the Mediterranean. In the rediscovered serenity of his Mediterranean retreat in the 1950s, an unexpected blossoming took place. In a series of charming works he depicted the thousand events of his daily life with his companion of the time Françoise Gilot and their two young children, under the multiple aspects of a family of fauns, playing the flute, jumping in the waves, play-fighting on the beach. In this same period of happy family life, Picasso, politically committed after Guernica, bore witness to his convictions with Mass Grave (Le Charnier) (1944), To the Spanish who Died for France (Aux Espagnols Morts pour la France) (1947), and Massacres in Korea (Les Massacres en Corée) (1951). In 1952 he completed the two large panels of War (La Guerre) and Peace (La Paix) for a disused chapel in Vallauris. In 1958 he painted the very large mural painting in the Palais de l'UNESCO in Paris, on a group of juxtaposed panels that could be taken apart. At the same time as painting these more memorable works, he painted a large number of landscapes, still-lifes and the Portrait of Madame H. P. (Hélène Parmelin-Pignon) in 1952, and the Portraits of Sylvette and Portraits of Jacqueline (Jacqueline Roque, his new companion) in 1954. Subsequently, in an output that was more diverse in both subject matter and technique, a significant part of Picasso's painting was devoted to variations of famous paintings, beginning in 1950 with Courbet's Les Demoiselles des Bords de la Seine and continuing with Delacroix's Women of Algiers (Les Femmes d'Alger). After the 1955-1956 Painter's Studios in the villa La Californie in Cannes (a clear tribute to Matisse who died in 1954), some 50 variations of Velázquez's Las Meninas were painted from 1956 to 1958. From 1959 to 1961, after a series of engravings of bullfights and rural scenes on linoleum in 1958-1959 and at the same time as the 1960 series of wash drawings and watercolours of Romancero of the Picador, Picasso painted 27 variations of Manet's Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe at Mougins in Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie. In 1962-1963 he produced a series of David's Rape of the Sabine Women. In 1963 he started the series of the Painter and his Model, which he continued working on until the end of his life and in which he developed an allegory of his obsession with the confused love-hate relationship between the woman and the painter. From the years between 1960 and his death in 1973, over 1000 paintings, prints and drawings have been listed. At nearly 90 he was still energetically creating a series of paintings or drawings full of joy, with the atmosphere of a Spanish fiesta, ironic self-portraits of an old man or a plumed musketeer, the most common of which illustrate lively erotic intrigues and bear the most eloquent witness to his indefatigable energy.

Picasso's vast collection of works can be divided into two dominant and antagonistic extremes: Analytical Cubism from 1910 to 1913, and the Cubo-Expressionism of Guernica from around 1937. Analytical Cubism, which is owed largely to Braque, is often linked, not without reason, to the Synthetic and Primitive Symbolism of Gaugin, the Formal Symbolism of Cézanne and the Esoteric Symbolism of Mallarmé, who died in 1898. With these painters, as with the poet, the apparent abstraction of the plastic or literary form does not rule out appreciable reality but deals with the basics. Almost all of Picasso's work, apart from that of Analytical Cubism, gives the impression that such an ascetically intellectualised approach was quite contrary to his extravert temperament, and the period of hard-line Cubism, with the exception of a narrative extension, was for him very short. On the contrary, almost all of his work is based, in its diversity, on Cubo-Expressionism (a term more appropriate than the more official Synthetic Cubism) which is still regarded as his own brand, his style, which, if it culminated with Guernica, was already completely present in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, and which turned out to be capable of illustrating the course of his own existence, his passions, his impulses, his admirations and his indignations throughout his life.

Choosing between the many classifications attributed to him and keeping only two, the first would surely be 'Demiurge', since, in so far as the fine arts are concerned, Picasso created a new world. According to Pierre Francastel, Picasso (with Cubism and, therefore, Braque) was the origin of the greatest pictorial revolution since the Renaissance. This radical judgement, justified as it may be, since there is clearly a Picassian world, seems to omit the fact that Impressionism, too, previously broke away from Classical perspective and in its way included the passage of time in the frozen work and, moreover, revolutionised the pictorial transcription of light and colours. It also omits the fact that Abstraction, concurrently with Cubism, fundamentally eliminated references to the real world.

'Protean', the second term, brooks no discussion. The scope of techniques, styles and themes that Picasso covered remains unimaginable and incomprehensible, all the more so since no list seems to have been made of all his works in every genre. What is perhaps most thought-provoking is the fact that the number of his works has not been calculated. There are other artists whose output is numerically considerable, although to a lesser extent, but these artists usually continue producing more of what they know how to do. This is not the case for Picasso, even taking into account that each phase gave rise to variations on a theme, and that they did not all reach the same level of intensity. It seems that throughout his very long career, he did his utmost to do what he did not previously know how to do and that, eventually, it emerged that he knew how to do everything. The total number of his works has been estimated at about 60,000. He was admittedly fully active for 365 days a year for 75 years, but this would mean that he must have produced 800 works per year; an average of two a day. Picasso's case will clearly remain inexplicable.

Picasso participated in many collective exhibitions, particularly the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in Madrid from 1897 onward. Between 1912 and 1914 he exhibited at the Jack of Diamonds in Moscow, the Armory Show in York in 1913, the first Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925, and many others too numerous to mention. Because of a commitment to the old tradition of the Paris Salons, he participated in the Salon de Mai from its creation in 1945 until the end of his life.

From quite early on in his career, Picasso showed collections of his work in an equally large number of solo exhibitions, including: at the Galerie Ambroise Vollard in Paris (1901);, at the Galerie Paul Rosenberg in Paris (showing Cubist still-lifes, 1920); again at the same gallery (1926); at the Chicago Arts Club (1930); a retrospective at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris (1932); at the Kunsthaus in Zurich; a touring exhibition in Spain (1936); at the New York Museum of Modern Art and the Chicago Art Institute (1939-1940); at the Salon d'Automne in Paris for the first time and with an entire room dedicated to him (1944); at the Maison de la Pensée Française in Paris (1949); at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyons and the Gallery of Modern Art in Rome (1953); at the Museu de Arte Moderna in São Paulo and the Maison de la Pensée Française in Paris (1954); at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, a retrospective where Guernica was seen for the only time in Paris since 1937 (1955); at the Museum of the Rhine in Cologne and the Kunsthalle in Hamburg (1956); at the New York Museum of Modern Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Fine Art (1959); at the Musée Cantini in Marseilles and the Galerie Louise Leiris in Paris (1959); at the Tate Gallery in London (1960); at the University of California in Los Angeles (1961); at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Montreal and the Toronto Art Gallery (1964); at the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse; Tribute to Pablo Picasso, a three-part retrospective exhibition in Paris for his 85th birthday (paintings at the Grand Palais, sculptures and drawings at the Petit Palais where the extent of his sculpture was seen for the first time, and graphic work at the Bibliothèque Nationale, 1966); and a new tribute for his 90th birthday, this time at the Louvre (1971).

A great many retrospective exhibitions were also held all over the world, especially the following: themed retrospectives regularly organized by the Musée Picasso in Paris, from its opening at the Hôtel Salé in 1985 until the 1996 Picasso: Le Portrait held in the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais; Picasso: Papiers Collés at the Musée Picasso in Antibes (1998); Picasso: Collection Jean Planque in the print room of the Musée Jenisch in Vevey (2001); Picasso Érotique at the Galerie Nationale de Jeu de Paume in Paris (2001); Picasso/Matisse at the Tate Modern in London and the Grand Palais in Paris (2002); Picasso: The Bull at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (2003); and, on the 30th anniversary of his death and in collaboration with the Léa Miller archives, Picasso: Voyage dans l'Amitié at La Malmaison in Cannes (2003).

"PICASSO, Pablo." In Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/benezit/B00141033 (accessed April 16, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, 1883 - 1966