Carrie Mae Weems

American, born 1953

Weems’s first major work, Family Pictures and Stories (1978–84), is a family album with images of her relatives interspersed with printed anecdotes and interviews that mines the history of her own family—sharecroppers who moved from Mississippi to Oregon in the early 1950s—as well as the language, relationships and history of African American families in general. In her subsequent series, Ain’t Jokin’ (1987–8), she superimposed racist jokes, riddles and epithets onto portraits of African Americans with wit and humour in order to provoke and confront viewers with their own prejudices and racist attitudes. Another series, American Icons (1988–9), consists of domestic still-life photographs with blackface memorabilia and figurines that take the form of racial stereotypes, such as Aunt Jemima salt and pepper shakers, exposing the way in which such material becomes a part of one’s home. In a later series, Weems offered an alternative to this type of collectible—ivory-coloured china plates inscribed with the achievements of African Americans (e.g. Commemorating, 1992).

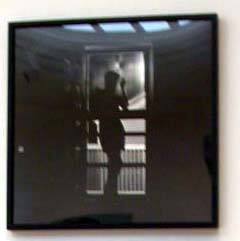

Weems cited the book The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), with photographs by Roy DeCarava and poetry by Langston Hughes, as one of her inspirations for interweaving words and images. She also discussed the importance of the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, as well as music, including jazz and the blues. In The Kitchen Table Series (1990), 20 images—each centered on a kitchen table where Weems is the protagonist among a cast of characters including the viewer, who sits at the far end—are interspersed with 13 text panels and audio recordings of conversations, anecdotes, slang and blues lyrics. The narrative reveals the complexity of life not only for African American families, but also for families in all communities.

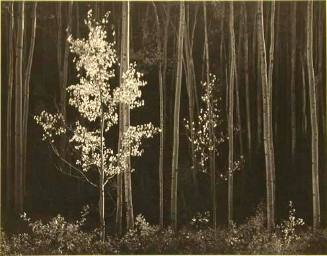

Weems explored the impact of slavery on American consciousness in Sea Island Series (1991–2), a group of documentary photographs taken on islands off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, where African culture is preserved by the Gullah-speaking people. These photographs are combined with text describing local stories, myths and rituals. Weems created the Africa Series (1993) after her first visit to Africa, combining images of traditional architecture with a story about the origin of life.

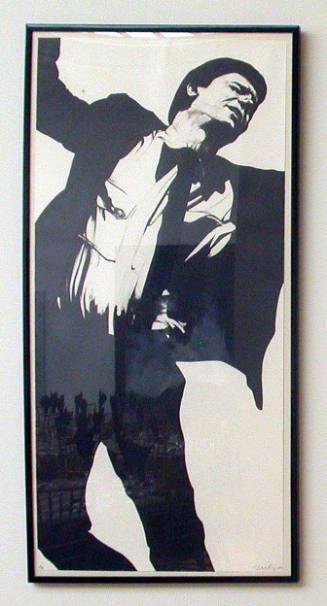

In From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995), Weems offers an alternative reading of African American portraits, ranging from mid-19th century daguerreotypes to 20th-century photographs, culled from the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum and a private collector. To create this work, she photographed the images and reprinted them in a blood red, invoking anger, with captions that read ‘A Negroid Type’ and ‘Others Said “Only Thing A Niggah Could Do Was Shine My Shoes”’. Weems’s critique and deconstruction of stereotypical and racist images of Africans and African Americans compels viewers to question their own reading and understanding of black history and their role in the current state of race relations.

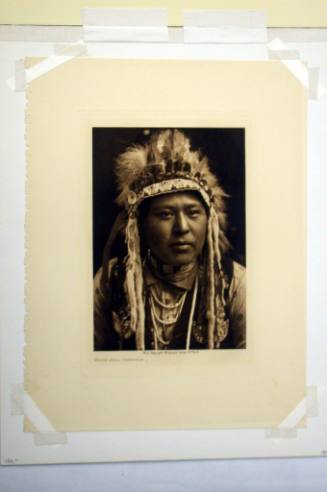

In addition to engaging viewers through images and texts hung on walls, Weems created visual and audio environments that immerse viewers in a retelling of events. In her later work, Hampton Project (2003), she appropriated documentary photographs taken in 1899 of the Hampton Institute in Virginia—an institution that educated African Americans and Native Americans by instructing them to break all ties with their cultural heritage and assimilate into white society. Weems recontextualized the photographs by reprinting them on canvases and large, translucent muslin banners hanging from the ceiling, interspersed and juxtaposed with the Institute’s photographs and ones from her own archives. With the layering of images and the recording of her voice saying ‘God and education had posed as the perfect package deal and your soul was the price of the ticket’, Weems engaged the oral tradition of conveying stories and histories as a means of giving voice and power to the dispossessed and silenced.

Weems’s photographs and installations both seduce viewers and challenge them to react against social injustices and oppression. Optimistic about the role of art as a catalyst for social change, Weems’s works prompts viewers to question their understanding and acceptance of their personal as well as collective histories.

Retrieved from Oxford Art Online: http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T2022226?q=Carrie+Mae+Weems&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit (Accessed Feb. 21, 2012)

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- female

- African-American