Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto

Italian, 1697 - 1768

Italian painter, etcher and draughtsman. He was the most distinguished Italian view painter of the 18th century. Apart from ten years spent in England he lived in Venice, and his fame rests above all on his views (vedute) of that city; some of these are purely topographical, others include festivals or ceremonial events. He also painted imaginary views (capriccios), although the demarcation between the real and the invented is never quite clearcut: his imaginary views often include realistically depicted elements, though in unexpected surroundings, and in a sense even his Venetian vedute are imaginary. He never merely re-created reality. He was highly successful with the English, helped in this by the British connoisseur joseph Smith, whose own large collection of Canaletto's works was sold to King George III in 1762. The British Royal Collection has the largest group of his paintings and drawings.

1. Life and work.

(i) Early works, c. 1716-30.

(a) Rome and Venice: Theatre and early capriccios.

His father, Bernardo Canal (1674-1744), was a well-established painter of theatrical scenery. The earliest source on Canaletto as a painter records that from 1716 to 1718 he was working with Bernardo and an uncle, Cristoforo Canal (d before 10 June 1730), on stage sets for operas by Antonio Vivaldi at the theatres of S Angelo and S Cassiano in Venice (Orlandi, p. 75). Around 1719 he travelled to Rome, again as his father's assistant, to paint scenery for Alessandro Scarlatti's operas Tito Sempronico Gracco and Turno Aricino, which were performed at the Teatro Capranica during Carnival 1720. This experience of scenery painting gave him a thorough grounding in draughtsmanship, perspective and quadratura. None of his stage sets has survived, but the designs for them were highly praised by Anton Maria Zanetti the younger (1771, p. 462), who also recorded that Canaletto could not adjust to working with theatre people and soon directed his talents to painting views, both real and imaginary (p. 463). Canaletto's Roman sojourn was crucial to his artistic formation and may have been much longer than the few months usually suggested. He was inscribed in the Venetian painters' guild, the Fraglia, in 1720, but this inscription could have been made during a brief visit home or even while he was still in Rome.

An important set of architectural drawings numbered 1 to 23 (all London, BM, except no. 19, Darmstadt, Hess. Landesmus.) have come to be viewed as the artist's earliest known works. They represent Roman sites or monuments, both ancient and modern, and bear inscriptions that are considered autograph (1981 exh. cat., no. 93, p. 81). But for several reasons-they differ markedly in quality and style, they are based in part on engravings by Giovanni Battista Falda and Etienne Dupérac and were used by Canaletto for paintings of his middle years-the questions of when and why they were made require further elucidation (Corboz, 1985, i, p. 30).

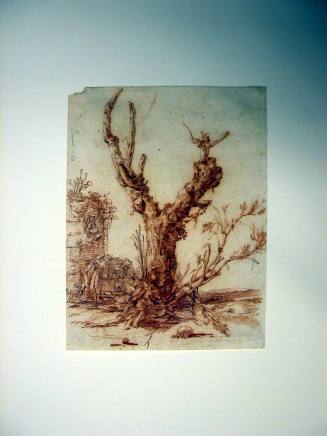

Having, in his own words, 'solemnly excommunicated the theatre' (Zanetti, 1771, p. 462), Canaletto appears to have tried his hand next at fantasy views and landscapes while gradually working his way into the more exacting art of realistic view painting. His early capriccios were probably made during or just after his stay in Rome. This early phase of his career remains insufficiently known, as many of the pictures are privately owned and not easily accessible, yet several have been identified (Morassi, 1956 and 1966). Most of these depict decaying edifices and architectural fragments, usually overgrown with foliage, or else Roman ruins, some real and some fantastic, often placed in a lagoon-like setting. They are painted in broad, loose brushstrokes on a dark ground and no doubt reflect Canaletto's stage-design manner. The few lively, sketchy figures serve mainly as colour accents. Two such typical early views are the pendants in the Cini collection in Venice (see 1982 exh. cat., nos 76-7). A large capriccio in a private Swiss collection (see Puppi, 1968, pl. 1) is inscribed 'Io Antonio Canal 1723'. The Landscape with Ruins and a Renaissance Building (Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum) is a particularly attractive painting and, significantly, it was formerly attributed to Marco Ricci.

Canaletto certainly saw Luca Carlevaris's capriccios and imaginary harbour scenes during his formative years in Venice. In Rome he must have encountered Baroque architectural compositions, such as those by Viviano Codazzi and Giovanni Ghisolfi, as well as Gaspar van Wittel's Roman vedute and possibly even Giovanni Paolo Panini's very early ruinscapes. Yet Ricci's works, often confused with Canaletto's, provided the greatest inspiration. The personal connection between the two artists was probably closer than has been suspected: in 1718 Ricci worked as stage designer in the same Venetian theatres as did the Canal family, and he, like Canaletto, may have been in Rome c. 1719-20.

Around 1725 Canaletto collaborated with Giovanni Battista Piazzetta and Giovanni Battista Cimaroli (fl c. 1700-after 1753) on the allegorical tomb painting Capriccio: Tomb of Lord Somers (c. 1725; Birmingham, Mus. & A.G.), and with Giambattista Pittoni and Cimaroli on Capriccio: Tomb of Archbishop Tillotson (priv. col., see 1989 exh. cat., nos 12-13), both part of a series commissioned by Owen McSwiny for Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond. Canaletto's contribution was to paint the extensive architectural settings and the sarcophagi. These, probably the last in date of Canaletto's youthful imaginary views, show the influence of Marco Ricci, who was also a contributor to the series. In 1727 McSwiny wrote to the Duke that 'Canal has more work than he can doe in any reasonable time and well' (quoted in Constable, 1962, i, app. II).

(b) Early Venetian townscapes.

Canaletto: Arrival of the French Ambassadors in Venice, oil on…In the 1720s Canaletto also painted realistic views, from 1725 to 1740 devoting himself almost exclusively, and with unrivalled success, to this genre. Some of his early townscapes appear to have been adapted from engravings and even from paintings by Carlevaris, supporting the hypothesis that after his return from Rome to Venice he spent some time in Carlevaris's studio. Among the earliest are four companion pieces: the Piazza S Marco and Grand Canal from the Campo S Vio (Lugano, Col. Thyssen-Bornemisza) and a less celebrated view, the shabby Rio dei Mendicanti, with Grand Canal from the Palazzo Balbi (Venice, Correr), which may be dated, on topographical evidence, to c. 1724. His first documented paintings, executed between August 1725 and July 1726, for Stefano Conti, a merchant of Lucca, were two pairs, the Grand Canal: Looking North from near the Rialto Bridge with the Grand Canal: The Rialto Bridge from the North, and the Grand Canal: From S Maria della Carità with SS Giovanni e Paolo and the Scuola di S Marco (all Montreal, priv. col., see Constable, 1962, i, pls 42, 48-9 and 58).

The letters (some in Canaletto's own hand) and memoranda pertaining to the Conti deal provide the richest single source of information on Canaletto in the 1720s (Haskell, 1956). They show that by 1725-6 he was very much in demand as a specialist of Venetian townscapes, having apparently surpassed Carlevaris's reputation in this genre; that he was particularly skilled at 'making the sun shine' in his pictures; that it was his custom to prepare his paintings outdoors 'on the spot' and 'not at home after an idea' as was Carlevaris's practice; that one of his views had entered the prestigious Sagredo collection and was hanging in the Sagredo family palazzo; and that on St Roch's feast day in 1725 he had astounded everyone in Venice with a picture of SS Giovanni and Paolo (untraced), which Conte Colloredo Waldsee, the Imperial Ambassador, had bought even though he already owned a picture by Canaletto.

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal): Piazza San Marco, oil on canvas,…The paintings themselves form the basis for dating a number of views painted c. 1722-8. These early works, including the Conti pictures, are mostly large and painted on dark reddish ground, hence dark in appearance. The paint is applied in thick, loose brushstrokes, with a ragged touch. The exaggerated foreshortenings and intense contrasts of light and shadow endow the views with a vivid immediacy, further enhanced by threatening storm clouds. Their theatricality may owe something to Canaletto's apprenticeship in scene painting, but the humid atmosphere of Venice is realistically rendered and the sketchy, incidental figures, always active and moving, attest to the artist's keen observation of daily life. The five large pictures in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, depicting similar subjects but compositionally more sophisticated, can be dated a little later.

The poetry and lofty mood of the townscapes of the 1720s, when Canaletto was not yet concentrating on celebrated sites for the tourist market, were never to be surpassed. The essence of his romantic style shows most vividly in a series of companion pieces, two horizontal and four upright, painted as part of a decorative ensemble depicting six sites in Venice as seen from the Piazza and Piazzetta (c. 1725; Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.). These were either acquired early on or, probably, commissioned by Joseph Smith. The powerfully realistic Stonemason's Yard (1726-7; London, N.G.), a vivid and intimate view of everyday life in Venice and of weathered and decaying buildings, is perhaps his masterpiece. The View of Murano from the Fondamente Nuove (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.) and the Molo Looking West: Fonteghetto della Farina (Venice, A. Giustiniani priv. col., see Puppi, 1968, pls 47-8) date from the same period. The two sun-drenched views commissioned by the Conte Giuseppe di Bolagno, the Bucintoro Returning to the Molo on Ascension Day (1730; Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.) and the Reception of the Ambassador (priv. col., see 1982 exh. cat., no. 84), and the famous Venice: The Feast Day of St Roch (London, N.G.), all painted c. 1730, mark the grand culmination of Canaletto's youthful period while heralding his mature style at its best.

(ii) Views of Venice and the patronage of Joseph Smith, 1730-39.

Canaletto was at his most productive and commercially successful during the 1730s, the decade in which he painted the views of Venice with which his name is associated. The majority of these works were made for affluent English patrons, who desired mementos of a visit to Venice, often made on the Grand tour. These clients approached Canaletto directly on occasion but usually through Joseph Smith, who had lived in Venice since c. 1700. Banker, shipping agent and, from 1744, consul, Smith was also a keen connoisseur of art, a great patron and a formidable collector. His palazzo, packed with pictures, was the chief meeting-place for English tourists. That Canaletto was working exclusively for Smith, as maintained by the Swedish diplomat Count Carl Gustav Tessin in 1736 (Links, 1977, p. 37) and again by Horace William Walpole in 1741 (Links, 1977, p. 37), overstates the case. Though the relationship with Smith must have started in the 1720s and lasted until Canaletto's death, no contract between the two men is known to have existed; rather theirs was an informal partnership that benefited both. Establishing contacts for Canaletto with prospective patrons and shipping his paintings to them in England put Smith in an advantageous position to acquire works by Canaletto for his own collection.

In 1735 the publishing firm of Giambattista Pasquali issued the Prospectus Magni Canalis Venetiarum, an album of 14 prints of Venetian views (12 of the Grand Canal, 2 of Venetian festivals; Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.); these were engraved by Antonio Visentini after paintings by Canaletto described on the title page as being in Smith's residence. In 1742 Smith had a new edition of the Prospectus published: to the first set it added 24 new prints, again engraved by Visentini, based on yet another cluster of Canaletto townscapes that Smith had acquired in the 1730s. By 1742 these view paintings, apart from 15 that Smith kept for himself, had been sold to various members of the English nobility. They were painted with tourists in mind and show noted Venetian sites, always in bright sunlight. On average they are of smaller size than his view paintings of the 1720s; the 34 vedute included in the two editions of the Prospectus are of uniform size, c. 480×800 mm, which was evidently a size that Smith liked to handle for Canaletto's run-of-the-mill output in those years (both size and format were particularly suitable for pictures that came in large sets). Among the English aristocrats who bought these view paintings were John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford (1710-71), and Francis Osborne, 4th Duke of Leeds (1685-1741), while no fewer than nine were acquired for an unidentified member of the Duke of Buckingham's entourage. By the 19th century Richard Grenville, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos (1823-89), owned 19 pictures (dispersed, but known as the Harvey group; see Constable, 1962, ii, p. 277, no. 188); 22 of 24 vedute commissioned by the 4th Duke of Bedford remain at Woburn Abbey, Beds. These two sets, roughly of Prospectus size and showing the Grand Canal, the area around the Piazza and various churches and campi, epitomize the style of the 1730s.

Although Canaletto occasionally still used the reddish-brown ground he had favoured in the 1720s, he painted most of his views for export on white, light grey or light cream grounds. His skies turned serenely blue, with spare white clouds; the atmosphere evaporated; the subdued colours of the juvenilia disappeared; bright local colours were applied to the costumes. The advent of the high Rococo in Venice brought a similar lightening of the palette to certain works by Pittoni, Piazzetta and Giambattista Tiepolo. It is a more pronounced feature of some of Canaletto's works than others, leading critics to speculate that he was consciously using two different modes according to his patrons' taste. But whether his style was influenced to this extent by his market is impossible to determine. Although some paintings of that era are visibly straight commercial products done to a formula, at full speed, the craftsmanship is always impeccable even when the overall effect is prosaic. Canaletto did not simply repeat compositions; in fact autograph replicas are extremely rare. It was during the 1730s that he developed the calligraphic shorthand of blobs, short curves and rigid short lines that he used most noticeably in painting the staffage, thereby rendering it more static. But however hasty the creation, the arrangement of stereotyped figures was always masterly. Corboz (1985, ii) catalogued some 200 Canaletto paintings as executed between 1731 and 1746. Not all of these were handled by Joseph Smith; unaccountably the loftiest of them seem to have eluded him (Links, 1977, p. 41). The famous Bacino di S Marco (c. 1735; Boston, MA, Mus. F.A.) and the pendants depicting the Entrance to the Grand Canal and Piazza S Marco (Washington, DC, N.G.A.) did not pass through his hands. They may have been acquired directly from the artist by Henry Howard, 4th Earl of Carlisle. The only adequately documented work of Canaletto's maturity is a superb painting of unusual iconography, Riva degli Schiavoni: Looking West (London, Soane Mus.). In February 1736 it was completed and delivered to Johann Matthias, Marshal von der Schulenburg, military commandant of Venice, who had commissioned it directly from Canaletto for the handsome sum of 120 sequins (Binion, 1990, p. 118). By late 1739 Canaletto was acclaimed by Charles de Brosses (Lettres familières écrites d'Italie en 1739 et 1744; ed. Paris, 1885, p. 399) as the greatest townscape painter of all time.

(iii) Etchings and capriccios, 1740-45.

In the early 1740s Canaletto gave up painting Venetian vedute almost entirely and devoted himself mostly to drawing and, probably for the first time, to etching. The change was largely due to the decline in English patronage after the outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession (1741), which made travelling hazardous and sending paintings to England risky. His change in medium was accompanied to a certain extent by a change in subject-matter: he gave preference to capriccios and landscapes over realistic townscapes. In 1740-41 he made a tour of the Brenta canal, as far as Padua, with his nephew Bernardo Bellotto, during which he made around 30 drawings from nature, such as the luminous Farm on the Outskirts of Padua (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.), which show a fresh and spontaneous response to a new source of inspiration.

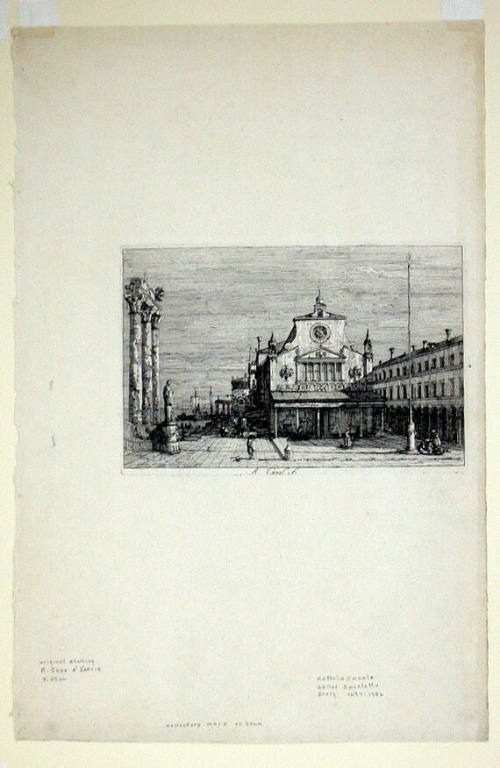

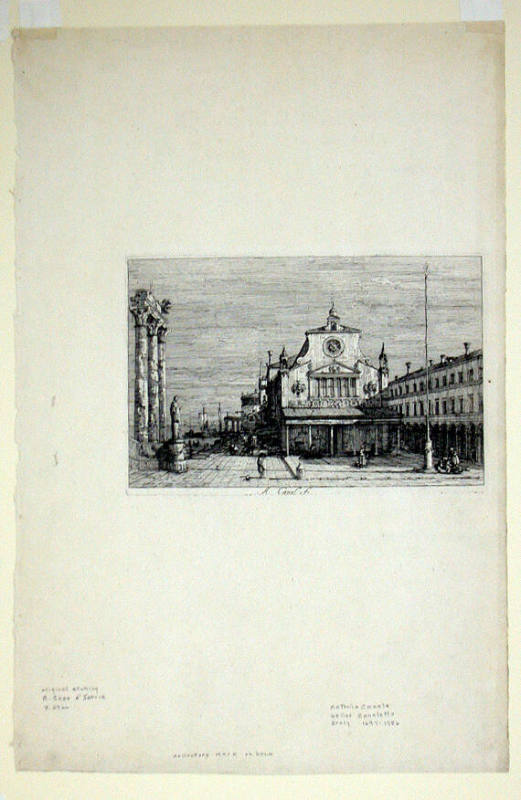

Throughout this period Canaletto was also working on etchings, which rank with the best ever produced. They fall within the great revival of etching in Venice that is represented in the work of Tiepolo, Piazzetta and Michele Giovanni Marieschi. Canaletto's style, though varying considerably from print to print, is distinguished by a wide range and great subtlety of tonal variation and a delicate, poetic rendering of light. Of the 34 items of his etched oeuvre, 31 were published in bound sets, with one third representing actual Venetian sites and the rest imaginary and untitled landscapes, suggestive of the countryside around Padua and along the Brenta canal. The etchings may have been commissioned and financed by Joseph Smith, for the title-page of the bound edition bears the dedication Giuseppe Smith Console di S.M. Britanica. The date of Smith's appointment to the post of consul, 6 June 1744, provides the terminus post quem for the collection's publication, and the year of Canaletto's departure for London, 1746, provides an ante quem. As the paper used for the etchings is said to have been produced between 1740 and 1743 (see 1986 exh. cat., p. 109), these years may well be considered as Canaletto's etching period, although the variety of technique and style within the set suggests that he experimented with the medium over an extended period, possibly between 1735 and 1744 (Bromberg, 1974). The sequence in the surviving original sets, such as that which belonged to Anton Maria Zanetti the elder (Berlin, Kupferstichkab.), was not based on chronology; what determined it remains to be discovered.

Etching may have been Canaletto's main preoccupation at this time, yet in 1743 he also received a large commission from Joseph Smith for 13 'pieces over doors', all of which were capriccios. Most of Canaletto's capriccios were executed after 1740, his interest in this form of painting perhaps reawakened because of the declining demand for topographical views. These later capriccios differ from his earlier ones in containing fewer invented architectural elements. Capriccio: The Horses of S Marco in the Piazzetta (1743; Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.) places the famous horses in a different, but real, setting. Sometimes the fancifully juxtaposed elements are taken from more widely separated locations and assembled in an imaginary setting, as in the capriccio that shows the Colleoni statue near a Renaissance church and Roman ruins, including the Colosseum (priv. col., see Constable, 1962, i, pl. 88, no. 477).

(iv) England, 1746-55.

Canaletto: Warwick Castle: The East Front, pen and brown ink,…In 1746 Canaletto, prompted by the decline of commissions in Venice, moved to England; George Vertue recorded his arrival in London in May of that year. Smith had provided letters of introduction, and McSwiny presented him to the Duke of Richmond. Canaletto was based in England until at least 1755, interrupting his stay in 1750-51 and again in 1753 to revisit Venice. In his first two years in England, he chose the Thames and the area around Westminster Bridge as his subject-matter. The bridge was then under construction and its supporting framework, scaffolding, crossed planks and poles gave him a series of attractive motifs, as in London: Seen through an Arch of Westminster Bridge (c. 1746-7; Alnwick Castle, Northumb.), which was painted for Hugh Smithson (later 1st Duke of Northumberland). The two imposing pictures London: The Thames on Lord Mayor's Day and London: The Thames with Westminster Bridge in the Distance, purchased by Ferdinand Filip, Prince of Lobkowitz (Prague, N.G., Kinský Pal.), were probably painted c. 1747. In the late summer of that year the Duke of Richmond permitted him to make drawings from the windows of Richmond House, overlooking the Thames, which resulted in two of his greatest English paintings, London: Whitehall and the Privy Garden and London: The Thames and the City of London from Richmond House (both Goodwood House, W. Sussex). London remained the centre of his activity, but after 1748 he spent prolonged periods away from the city, painting his patrons' country seats and domains (see fig.). For Charles Noel Somerset, 4th Duke of Beaufort (d 1756), for instance, he painted Views of Badminton (1749; Badminton House, Glos; in situ). Towards the end of his stay in England he received a major commission from a friend of Joseph Smith, Thomas Hollis, and the paintings produced for this eccentric individual illustrate the varied quality of Canaletto's English output. Thus Ranelagh: Interior of the Rotunda (1754; London, N.G.) is unusually pedestrian, while Old Walton Bridge over the Thames (1754; London, Dulwich Pict. Gal.) is a spirited masterpiece. His English oeuvre is not massive; no more than 40 paintings of English subjects are known. It may be that he went on producing Roman and Venetian vedute, even in the form of drawings, and that many of his imaginary views and capriccios that cannot be dated were made in England. Judgements of this period range from high praise to denigration. That he 'saw London through Venetian eyes' (Constable) is true, but that he never succeeded in capturing and rendering the poetry of the northern light is debatable. The claim that he developed his mechanical touch in England is inaccurate, for his calligraphic mannerisms are evident in works made in Venice many years earlier.

(v) Last years, 1756-68.

Though the year of Canaletto's return from England to Venice is not known, he seems to have spent at least the last decade of his life in Venice. Some 40 paintings-both townscapes and architectural landscapes-and just over 100 drawings from these years have been identified (Corboz, 1985, ii). The drawings show a marked preference for fanciful compositions and capriccios over topographical views.

Canaletto was not among the 36 founder-members of the Accademia Veneziana di Pittura e Scultura (founded 1750, officially recognized 1756); only in 1763 did he become a member. He submitted his reception piece in 1765, choosing as its subject an architectural capriccio, a Colonnade Opening on to the Courtyard of a Palace (Venice, Accad.). That increasing age and illness accounted for the relatively slim output of his last ten years is questionable. His style had become highly mannered and is often viewed as dry and hard; yet most of the works are vigorous and remarkably well conceived, among them the untitled series of capriccios engraved by Fabio Berardi (1728-88) and published by Joseph (Giuseppe) Wagner (1706-80) and the ten very large drawings of the ducal ceremonies and festivals (one in London, BM) engraved by Giambattista Brustolon and published soon after 1763. The latter series proves that his skill in rendering large crowd scenes effectively was altogether unimpaired. The last dated work from Canaletto's hand is a drawing of the Cantoria of S Marco with its Musicians (Hamburg, Ksthalle). It bears an autograph inscription stating that he made it in 1766 at the age of 68 'without spectacles'. Canaletto died two years later after a short illness and was buried where he had been baptized, in the parish of S Lio. His three sisters inherited his estate, which the inventory made on his death reveals to have been modest. There were 28 pictures found in his studio, presumably unsold works by him; to posterity he left over 500 paintings and an even greater number of drawings of inestimable value.

2. Working methods and technique.

(i) Drawings and etchings.

Canaletto was a superb and prolific draughtsman, and his 500 known drawings represent only a fraction of his total graphic output. The vast majority consist of elaborate, nearly finished compositions; a mere handful of his figure studies have been identified, for example Three Groups of Figures: Market Scenes (pen and brown ink; Rotterdam, Mus. Boymans-van Beuningen), and first thoughts and compositional studies are extremely rare. During the later part of his career many were made for the engraver or as ends in themselves. He used white paper to draw, no doubt because of his constant interest in rendering light, primarily sunlight, and its effects. He drew with the pen, using various types of quill, occasionally a reed and even metallic pens (Parker, 1948, p. 22). A graphite or chalk foundation or rough tracings in chalk can almost always be detected under the actual penwork, as in Two Studies of Men Standing (New York, Met.). In the early part of his career Canaletto used tight pen hatchings for his shadows; then, from the mid-1730s, he switched to ink washes instead, probably to save time. He used rulers and dividers extensively. He used sketchbooks and albums for drawing, as is suggested by the numbers on some isolated sheets, but these were dismantled and have been reassembled only in part.

The Cagnola sketchbook (early 1730s; Venice, Accad.) is particularly informative on Canaletto's working methods. Its 75 numbered sheets contain 138 diagrammatic sketches of Venetian architectural sites, especially of buildings on the Grand Canal always viewed from the water. Profusely annotated in Canaletto's hand, it contains factual material set down by the artist on the spot in black or red chalk, then apparently gone over with the pen later in the studio and expanded. The question of whether Canaletto used the camera obscura for the diagrams has been debated hotly but inconclusively (Pignatti, 1958; Gioseffi, 1959). That he used mechanical aids such as dividers, rulers, compasses and, presumably, optical instruments, has never been seriously denied. Zanetti (1771, p. 462) speaks of his using the camera obscura and knowing how to correct for its distortions. In all likelihood he used it as an aide-mémoire for jotting down an overall view of some site, which he called a scaraboto, or some rough outline of a scene. He certainly did not use it for a careful and detailed recording of scenes to be transposed unchanged on to canvas. The works themselves belie such a procedure. His vedute are never topographically accurate even though they remain convincing as such, as they did to his patrons. A careful scrutiny of his views shows that he always manipulated the topography, at times extensively, combining two or more viewpoints, then unifying the whole through the fall of light. The departures from reality in the interest of overall design led him to change the proportions of the buildings and to widen and narrow the distances between them. Frequently he would suppress specific architectural elements (e.g. one of St Mark's cupolas) to achieve a better composition.

The purpose of many of Canaletto's drawings is unclear. A group of 142 drawings made in the 1730s is particularly puzzling. All were in Joseph Smith's collection. There is no evidence that anyone besides Smith showed interest in Canaletto's drawings at that time. It is not unlikely that Smith in his role of impresario assembled these drawings in a catalogue of Venetian subjects from which prospective customers might pick. Alternatively he may have kept them as mementos or records of the pictures that had passed through his hands. Or perhaps he was simply the first to recognize Canaletto's genius as draughtsman.

Canaletto's etching style is highly individual. He probably learnt to etch on his own, drawing directly on the copper plate, although some reminders of Marco Ricci's etching style can be detected, as in the handling of the sky. No trace of elaborate preparations or of counterproofs has emerged.

(ii) Studio practice and influence.

Many of Canaletto's works of the busy 1730s were copied. There is no reason to believe that these copies were produced in his workshop or even that he had a large team of assistants. In all likelihood his studio was a family workshop. His father, Bernardo, only 56 years old in 1730, did more than just lend a hand. And his nephew, the precocious and highly gifted Bernardo Bellotto, who became a member of the Fraglia as early as 1738, no doubt supplied substantial help during an apprenticeship that must have lasted from 1734 to 1740. No serious evidence has emerged to date of Michele Marieschi or Francesco Guardi having spent any time in Canaletto's studio or having collaborated with him. His influence on the English school of painting, especially Samuel Scott, has not been sufficiently investigated. In the opinion of Waterhouse (1969), when Canaletto left England in 1755 he had established the vogue for views of London, especially the reaches of the Thames, and had laid the groundwork for an English school of topographical art.

Alice Binion. "Canaletto." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T013627 (accessed March 22, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, 1720 - 1778

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665

Italian, 1692 - 1770