Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione

Italian, c. 1610 - 1665

(not assigned)Genoa, Liguria, Italy, Europe

BiographyBorn Genoa, bapt 23 March 1609; died Mantua, 5 May 1664.Painter, printmaker and draughtsman. Most of his works are scenes of the journeys of the patriarchs (e.g. Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob), drawn from the book of Genesis and filled with animals and still-life detail. His oeuvre also, however, includes many spectacular mythological and religious compositions set in expansive landscapes, and for these he found inspiration in Classical mythology, ancient history, Aesop’s Fables, 16th-century Italian literature and the lives of the saints. Early biographers claim that he was also a prolific portrait painter, but few examples, save the so-called portrait of Gianlorenzo Bernini (c. 1648–50; Genoa, Pal. Bianco), have been conclusively identified. His surviving subjects reveal his interest in magic and metamorphosis and in philosophical questions such as the frailty of human life, the inevitability of death and the search for truth. He is celebrated for the virtuosity of his execution, most brilliantly revealed in his many pen-and-ink drawings, dry-brush oil sketches, etchings and monotypes (a printmaking technique invented by him).

1. Life and work.

(i) Formative years in Genoa, to c. 1628.

Castiglione is documented in the studio of Giovanni Battista Paggi from 1626 until May 1627 and through him became aware of the wide variety of styles then current in Genoa, which included late Mannerism, early Baroque classicism, Flemish naturalism and an indigenous Genoese realism. Through Paggi’s library and collection of prints, Castiglione was introduced to the work of many Italian and northern European printmakers, and he later found the motifs and compositions from a vast body of Italian prints an almost endless source of material for his own works. His eclecticism would have been influenced by theoretical discussions with Paggi, and his art underwent numerous stylistic mutations throughout his career. While it is not certain, as the early biographies suggest, that he also studied with Giovanni Andrea de’ Ferrari, Anthony van Dyck (Soprani, p. 223) and Sinibaldo Scorza (Pio), he was influenced by each of them. He may have begun to create dry-brush oil sketches on paper, perhaps inspired by the oil sketches of Rubens and van Dyck, as early as the late 1620s. No documented works from these formative years are known, yet his later art reveals his interest in the animal-filled landscapes of Scorza and Jan Roos (1591–1638), and in the Bassano family’s earthy biblical scenes. His interest in landscape may reflect an early knowledge of the art of Agostino Tassi and Goffredo Wals, both of whom had worked in Genoa.

(ii) Rome and Naples, c. 1629–38.

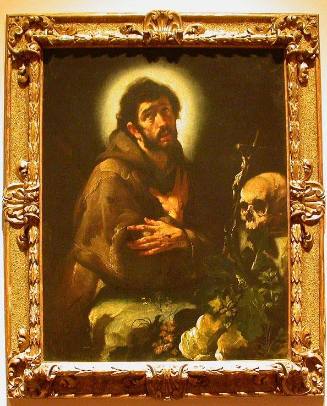

Castiglione left for Rome between 1627 and 1631. He is documented there in 1632, and he was joined by his brother (2) Salvatore Castiglione in 1634. His first known signed and dated picture is Jacob’s Journey (1633; New York, priv. col., see 1990 exh. cat., fig.). Here the idealized landscape and the basing of the figure of Jacob on the Apollo Belvedere (Rome, Vatican, Mus. Pio-Clementino) suggest a link between Castiglione and his contemporaries Poussin and Claude, yet the attention to detail in the depiction of nature also suggests the influence of Scorza and Roos. The same stylistic complexity is evident in the charming depiction of the Penitence of St Peter.

Castiglione rapidly became known for his depictions of patriarchal journeys, and a court deposition of 1635 describes him as ‘He who often paints Jacob’s journeys’. In many of these compositions, carried out in different media, such as the Sacrifice of Noah (c. 1635; Genoa, Pal. Bianco) and the related brush drawing, Noah Entering the Ark (Paris, Louvre), the foreground is piled high with farmyard animals and fowls, with horses and donkeys loaded with pots and pans, and with a rich array of still-life objects such as gleaming copper vessels and wicker baskets.

The court deposition of 1635 also reveals that shortly after the Carnival of that year Castiglione went to Naples. No documents regarding his whereabouts or works there have been discovered, and it is not known why he went to Naples, how long he stayed or what he accomplished during this visit. Nonetheless, many pictures attributed to him are listed in Neapolitan inventories, suggesting that eventually he came to be widely admired in the city. Castiglione was interested in the art of Ribera, and he may have wished to deepen his knowledge of Neapolitan painting; another connection may have been Domenichino, who admired Castiglione and had arrived in Naples some time before 1635. Castiglione’s art had an impact on a number of Neapolitan painters, among them Nicolo de Simone and Andrea di Lione, both of whom painted patriarchal journeys.

Castiglione is next recorded in Genoa in 1639. It seems likely that he visited Rome on his way back to his native city: in the late 1630s he made a number of dry-brush drawings of mythological scenes and scenes from the story of Moses after paintings by Poussin that are generally dated to 1637 and 1638. These include the two that are now in the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, the Saving of the Infant Pyrrhus, which is loosely modelled on Poussin’s rendering of the subject (1637–8; Paris, Louvre), and the Adoration of the Golden Calf, based on Poussin’s painting in the National Gallery, London.

(iii) Genoa and Rome, 1639–51.

Castiglione remained in Genoa throughout most of the 1640s, and there are many pictures attributed to him in the inventories of prominent Genoese families such as the Spinola, Raggi, Balbi, Doria, Durazzo, Invrea and Lomellini, suggesting that he became one of the most important artists in the city. His first major documented altarpiece, the Nativity (1645; Genoa, S Luca), commissioned by the Spinola family, is a monumental composition rendered with a great variety of chromatic range, tonality and handling. In it Castiglione blended his robust bucolic style with a new grace and sweetness, reminiscent of both Correggio and Parmigianino, and created a new and intensely personal poetry. The success of this work probably helped him win commissions for the St James Driving out the Moors (c. 1646; Genoa, Oratory of S Giacomo della Marina), a dramatic work, suggesting Rubens’ influence, and St Dominic of Soriano (c. 1647; Sampierdarena, nr Genoa, S Maria della Cella). In this period he also painted exuberant and earthy antique bacchanals and sacrifices, and his secular compositions, which include the Allegory of Abundance (Genoa, Pal. Doria, see 1971 exh. cat. by Percy, fig.), Venus in Vulcan’s Forge (Genoa, Pal. Doria) and a highly finished brush drawing of Pagan Sacrifice (Chicago, IL, A. Inst.), convey the artist’s strong sense of self-confidence in his emerging stylistic vocabulary.

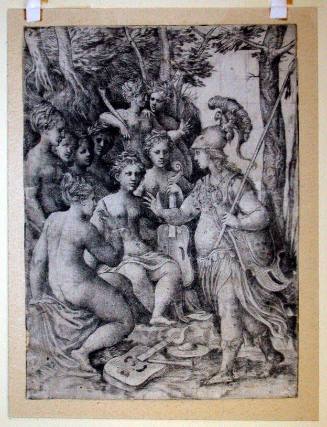

In the mid- to late 1640s Castiglione was also active as a printmaker and consigned a number of prints to be published by Giovanni Giacomo and Giovanni Domenico de Rossi in Rome. The prints spread his fame and their new and wider range of subjects suggests Castiglione’s growing ambition; his etching of the Genius of Castiglione (P E16; see also [not available online]) is a proudly proclaimed personal statement. In many etchings he portrayed subjects that emulated and may have influenced contemporary artists such as Poussin, Pietro Testa and Salvator Rosa, who shared Castiglione’s interest in unusual and erudite philosophical subjects. In this vein he rendered themes that suggest the transience of human achievement, such as Temporalis aeternitas (1645; p E13), Melancholia (c. 1646; p E14) and Diogenes Seeking an Honest Man (c. 1646; p E15); scenes inspired by ancient myth and fable, such as Theseus Finding his Father’s Arms (1645; p E12) and Marsyas Teaching Olympos the Various Musical Modes (c. 1646; p E11); religious subjects inspired by the lives of the saints and the Old and New Testaments, such as the rare scene of the Bodies of SS Peter and Paul Hidden in the Catacombs (after 1647; p E21), the Raising of Lazarus (after 1647; p E22) and Noah and the Animals Entering the Ark (c. 1650; p E24). Many of these are elusive, mysterious works, in which crumbling antique tombs, monuments and pyramids suggest the vanity of human endeavour.

Castiglione’s mature prints, many of which are night scenes lit by torchlight, reveal his attraction to Rembrandt’s strong chiaroscural etchings of the early 1630s. At this time Castiglione also began to develop the technique of the monotype (see Monotype, §1), a unique print made from an image transferred from a painting made on a metal plate, for creative purposes. Saul and David (Parma, Pal. Com.) is one example of this process. In several cases his monotypes reverse the compositions of his etchings, as in Temporalis aeternitas (1645; p M2), the Bodies of SS Peter and Paul Hidden in the Catacombs (p M5) and Theseus Finding his Father’s Arms (p M3), all of which are intensely dramatic nocturnal scenes that depend on brilliant effects of white on black.

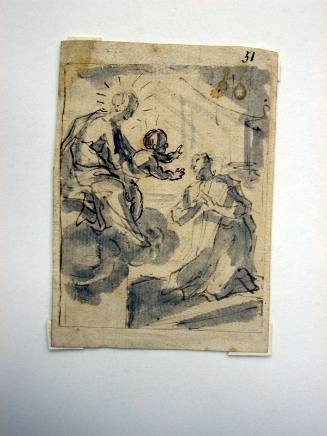

In the late 1640s Castiglione returned to Rome, where he is recorded as living with his family in 1648. It seems likely that he sold most of his canvases as ready-for-sale pictures to Genoese and Roman collectors, although he continued to receive important commissions for major altarpieces, such as the Immaculate Conception Adored by SS Francis and Anthony of Padua (1649–50; Minneapolis, MN, Inst. A.), commissioned by the Fiorenzi family of Osimo. He also collaborated with Viviano Codazzi, Filippo Gagliardi (d 1659) and other artists.

(iv) The late years in Genoa and Mantua, 1652–64.

Castiglione returned to Genoa in 1652 and seems to have kept a residence there throughout the decade, although he divided his time between Genoa, Venice (1659 and 1660), Parma (1661) and Mantua, where brief visits are recorded (c. 1659, 1661 and 1663). He continued to paint patriarchal journeys, such as the Journey of Abraham (1652; Genoa, Pal. Spinola), and unusual mythological scenes, such as the Deucalion and Pyrrha (1655; Berlin, Bodemus.). These works are characterized by their vibrant handling, elegantly mannered figures and beguiling imagery; they attained a new monumentality and drama, while the artist’s execution and palette reveal the influence of Venetian painting techniques of the late 16th century. A small Crucifixion (Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco) and a late monotype of the same subject (p M7) movingly convey an intense spirituality that is characteristic of a number of Castiglione’s late devotional works and is a quality for which he was perhaps indebted to van Dyck.

In the 1650s Castiglione began to be patronized by various members of the court of Carlo II Gonzaga, 9th Duke of Mantua, although his contacts with the court are not documented until April 1659. He continued to send pictures to clients in Genoa and Venice, but the bulk of his work was for Mantuan patrons. Perhaps the most spectacular of his Mantuan commissions, and a picture that contains many of the stylistic and iconographic themes of his art, is the octagonal Allegory in Honour of the Duchess of Mantua (c. 1652–3; Genoa, priv. col., see 1990 exh cat., pl. 25). Its companion, Temporalis aeternitas (Malibu, CA, Getty Mus.), recalls the motif of Poussin’s Arcadian Shepherds (Paris, Louvre), and both pictures are meditations on the vanitas theme.

Castiglione’s court duties included travelling to buy pictures for the Duke, and in 1661 he and his brother Salvatore were involved in unsuccessful negotiations to purchase the collection of Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale. Castiglione is not mentioned in the Gonzaga archives after 1662, but in 1663 he painted the Patriarchal Journey now at Capodimonte, Naples. The inscription on his tomb (Mantua Cathedral) wrongly indicates that he died in 1665.

2. Working methods and technique.

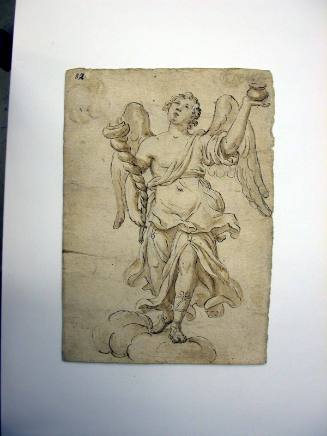

Castiglione’s art is distinguished above all by the virtuosity of its execution. In his paintings the use of a red-brown ground creates a rich tonality and warm, atmospheric effects against which are set strong reds, blues, greens and golds. His pen-and-ink drawings, such as the Melancholia (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Lib.), are characterized by their nervous and elegant line and delicate use of wash. In a series of highly inventive dry-brush drawings, Castiglione applied brushes filled with oil to dry pigments and drew on unprimed paper (see fig.). In many of these drawings he varied his handling between transparent and opaque passages, and, following the example of some late 16th-century Venetian painters as well as van Dyck and Rubens, he sustained a highly chromatic palette ranging from burnt sienna or rusty browns for his initial underdrawings, to Indian and Venetian reds, whites, burnt carmine or crimson lake for his highlights. His frequent use of buff paper and added touches of red or black chalk and sometimes pen and ink increased the visual impact of many of these drawings. Castiglione’s etching technique, with its play of light and shade, was deeply influenced by Rembrandt; his monotypes are closely related to his etchings and may have developed from his experiments on trial counterproofs for some of the compositions that he wished to develop further with an extended palette.

Castiglione frequently appropriated motifs from other artists, a not uncommon practice at the time. He borrowed from, among others, Poussin, Ribera and Rembrandt, whose etching of Christ Brought before Pilate (1634–5) inspired a number of figures in Castiglione’s drawings and in at least one of his paintings. The latter’s drawing of Lucius Apuleius Changed into a Donkey (1635–40; New York, Pierpont Morgan Lib.) was based on a similar composition by the Master of the Die in the Fable of Psyche, and in the late 1650s he recast the figure of St Mark (Los Angeles, CA, Co. Mus. A.) after Correggio’s rendering of the same subject in one of the pendentives in Parma Cathedral. This practice doubtless added authority to his work, but he also borrowed material in order to concentrate on the execution of the work, which could be seen as a means of giving a new inflection to traditional subjects.

Although there are a few remaining sheets filled with a number of small compositional studies in pen and ink (e.g. Oslo, N.G.), it seems clear that Castiglione rarely laboured over the design of his figures or compositions, preferring instead to focus on colour, atmospheric qualities and execution, concerns that may have emerged as he worked. Castiglione’s works in all media are closely related in style and composition, and it seems likely that he recycled many of his compositions by simply transposing a design in one medium over to another, allowing the basic lines of the image to be repeated, as in the etching and monotype Temporalis aeternitas (1645; p E13, M2).

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

Indications of Castiglione’s fame appeared as early as 1634, when one of his pictures, probably the Penitence of St Peter, was described in a book of verse entitled L’Apollo published that year by Ottavio Tronsarelli, a poet associated with the Barberini circle. Castiglione’s earliest biographers, Raffaele Soprani, Carlo Giuseppe Ratti and Nicola Pio, praised his technical brilliance and commented on his attempts to imitate a wide variety of styles in his formative years. Many painters in Italy were influenced by him: Sebastien Bourdon and Andrea di Lione imitated his patriarchal journeys in the late 1630s, and in Genoa Anton Maria Vassallo produced pictures so close to his style that they continue to confuse connoisseurs. Domenico Piola was also influenced by him, particularly in the 1640s. In the 18th century Castiglione’s art was especially popular in Venice. Zaccaria Sagredo’s fine collection of drawings, admired by Francesco Algarotti, was bought by Consul Joseph Smith for George III of England. Anton Maria Zanetti the elder possessed a collection of his drawings, from 12 of which Gaetano Gherardo Zompini engraved Varii capricci e paesi inventati (Venice, 1786). Castiglione’s etchings, with their picturesque Classical fragments and exotic figures, influenced the capriccios of Giambattista Tiepolo.

Evidence of the artist’s fame north of the Alps emerged as early as 1638, when a picture by Castiglione, described as the ‘Départ de Tobie et de sa famille’, was listed among the works owned by Charles de Blanchefort de Crequy. The painting was later bought from the collection by Cardinal Richelieu. A work by Castiglione was recorded in the French royal collection in 1665, and 47 of his prints were described by the Abbé Michel de Marolles in his Catalogue de livres d’estampes in 1666. The romantic classicism of these prints encouraged the development of the Rococo style exemplified in the work of Watteau and Boucher. Castiglione’s reputation declined during the 18th century, perhaps because there were so few of his works in public collections. He benefited greatly, however, from the general re-evaluation in the 20th century of 17th-century Italian painting, and the continuing interest in his work may be due to a modernist sensitivity to his virtuosity and to his pre-Romantic bohemian spirit, which emerges in the early biographies; also to his compelling images and wide variety of themes.

Timothy J. Standring. "Castiglione." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T014721pg1 (accessed April 10, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual

Italian, about 1520 - 1563