Alessandro Magnasco

Italian, 1667 - 1749

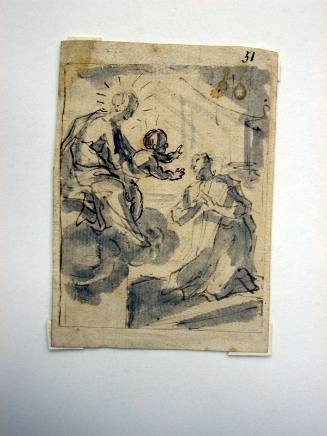

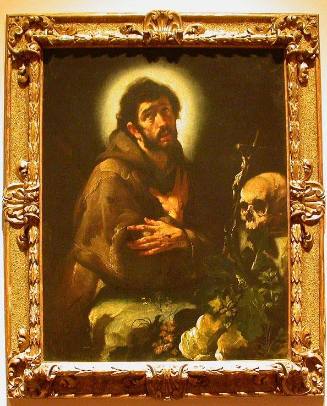

Painter and draughtsman, son of Stefano Magnasco. He did not study with his father, who died when he was a small child. He went to Milan, probably between 1681 and 1682, and entered the workshop of Filippo Abbiati (1640–1715). His Christ Carrying the Cross (Vitali, priv. col., see Franchini Guelfi, 1987, fig.) faithfully repeats the subject and composition of Abbiati’s painting of the same subject (Pavia, Pin. Malaspina). Alessandro Magnasco’s early works were influenced by the harsh and dramatic art of 17th-century Lombardy, with dramatic contrasts of light and dark and livid, earthy tones, far removed from the bright, glowing colours of contemporary Genoese painting. The depiction of extreme emotion in the St Francis in Ecstasy (Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco) was inspired by Francesco Cairo’s Dream of Elijah (Milan, S Antonio Abate). However, Magnasco was already expressing himself in a very personal manner, with forms fragmented by swift brushstrokes and darting flashes of light. The Quaker Meeting (1695; ex-Viganò priv. col., see Franchini Guelfi, 1991, no. 18) is one of his first genre scenes. In this early period he specialized as a figurista, creating small human figures to be inserted in the landscapes and architectural settings of other painters. He also began collaborating with the landscape painter Antonio Francesco Peruzzini, with a specialist in perspective effects, Clemente Spera, and other specialist painters; it was not until between 1720 and 1725 that Magnasco himself began to create the landscapes and architectural ruins that provide the setting for his figures.

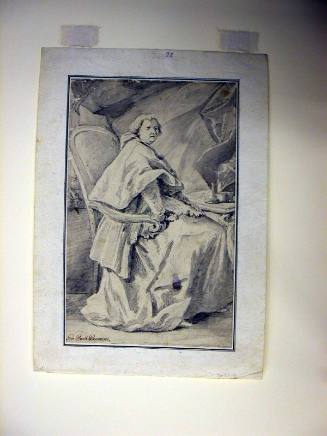

From about 1703 to 1709 Magnasco was in Florence, where he and Peruzzini worked for Grand Prince Ferdinand de’ Medici and his highly cultured court. The Journey of the Monks (Turin, Gal. Sabauda), the Old Woman and the Gypsies (Florence, Uffizi) and other paintings now in the Uffizi and Pitti in Florence were completed during this period. In the witty Hunting Scene (Hartford, CT, Wadsworth Atheneum) Magnasco portrayed himself and his friend the painter Sebastiano Ricci on a hunting expedition with Ferdinand de’ Medici and his court. During these years Magnasco began to experiment with a wide range of subjects drawn from varied sources. He found inspiration in prints, such as those of the series on the Quakers after Egbert van Heemskerck, and painted three scenes inspired by Jacques Callot’s Misères de la guerre: the Inquisition (Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.), the Entry to the Hospital (Bucharest, Mus. A.) and the Sacking of a City (Sibiu, Bruckenthal Mus.). He responded to the ironic low-life paintings by Dutch and Flemish artists, of which there were many in the Medici collections, and the lively court of Ferdinand encouraged an interest in burlesque art. Two popular literary genres, the Spanish picaresque novel and the literature of the pitocchi (sea beggars), which related the adventures of vagabonds, beggars, gypsies and footpads in tones ranging from the dramatic to the grotesquely comical, provided a further source of inspiration.

After returning to Milan, probably in 1709 (it is not known when he made the stay in Venice reported by his biographer, Carlo Giuseppe Ratti), Magnasco worked for the Lombard aristocracy, continuing to collaborate with Peruzzini and Spera but also experimenting with completely new subject-matter, as in the Capuchin Friars’ Refectory, the Capuchin Friars Studying and the Catechism in Church (all Seitenstetten Abbey, Austria), painted between 1719 and 1725 for Conte Gerolamo Colloredo, the Austrian Governor of Milan. These works, and others completed during the succeeding period, such as the Satire of the Nobleman in Poverty (Detroit, MI, Inst. A.) and The Synagogue (Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.), suggest the artist’s active participation in the intellectual debates of advanced aristocratic circles. His clients included such celebrated and progressive families as the Borromeo, the Archinto, the Arese, the Visconti and the Casnedi. In the first half of the 18th century in Milan, protests against corruption in the monastic orders, religious intolerance and social prejudice and ignorance began to be expressed in circles that were particularly sensitive to the new ideas of the Enlightenment emanating from France, Austria and the countries of northern Europe.

Magnasco returned to Genoa in 1735, remaining there until his death. His oeuvre shows contacts with the Genoese school in which his father had trained (Valerio Castello, Domenico Piola, Gregorio de’ Ferrari), in its rhythmically disjointed brushwork and drapery and its flowing continuity of figures and gestures, as can be seen in St Ambrose Expelling Theodosius from the Church (Chicago, IL, A. Inst.) and the Massacre of the Innocents (The Hague, Mauritshuis). Yet in other ways his art contrasts sharply with the bright and glowing colours of Genoese decorative painting. In Magnasco’s paintings the small figures are corroded by shadow, the colours are dull and leaden, almost monochromatic, and the swiftly executed brushstrokes are filled with tension. There is no serenity, and no easy visual pleasures are offered by his subjects, which express, particularly in the artist’s final years, deeply felt moral judgements on the realities of the day, as in the Arrival and Torture of the Prisoners and the Embarkation of the Galley Slaves in Genoa Harbour (c. 1740; both Bordeaux, Mus. B.-A.). The Sacrilegious Theft (Milan, Pal. Arcivescovile), an ex-voto completed in 1731 for S Maria at Siziano near Pavia depicting the Virgin putting to flight thieves who had broken into the church by night, seems to anticipate Goya in the terrifying presence of skeletons and the macabre nocturnal atmosphere, as do the four fearsome Witches (priv. col., see Franchini Guelfi, 1977, pls xli–xliv). In his final years Magnasco’s rapid brushstrokes, as in the Supper at Emmaus (Genoa, Convent of S Francesco d’Albaro), suggest fleeting effects of light, dissolving solid forms, while in the Entertainment in a d’Albaro Garden (Genoa, Gal. Pal. Bianco) his total rejection of formal Rococo frivolity is expressed in the portrayal of the petty and futile life of an aristocratic family.

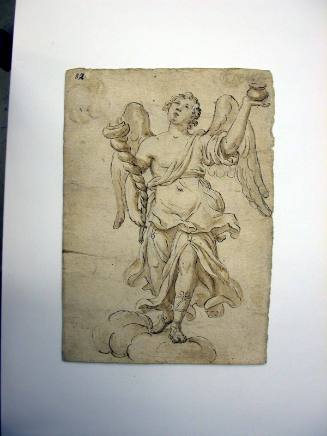

Magnasco left many drawings, and there is a large group in the Uffizi, Florence. Woodcutters and Fishermen and Two Pilgrims and a Seated Woman (both Florence, Uffizi) are characteristic of his fluid and expressive studies, in black and red chalk, for the figures that enliven his pictures. There are few compositional studies. He has evoked a variety of critical reactions. He was vastly successful during his own lifetime, as is shown by the large number of works by pupils and copyists that repeat the iconography and stylistic characteristics of his paintings. Forgotten during the 19th century, he was rediscovered in the early years of the 20th century by Benno Geiger, who compiled the catalogue of his works.

Federica Lamera and Fausta Franchini Guelfi. "Magnasco." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053137pg2 (accessed April 11, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual