Image Not Available

for Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas

American, 1899 - 1979

He studied at the University of Nebraska, from which he graduated, as well as Columbia University Teachers College. His artistic career began as an illustrator, working in ink drawings.

In 1925, attracted by the presence of Alaine Locke, philosopher and cultural critic, Douglas moved to Harlem, New York to be part of Lockes' New Negro Movement. This movement expressed African Americans' new pride in their African heritage, manifesting itself in literature, song, dance, and for Douglas, most significantly art.

Shortly after his arrival in Harlem, Douglas made the acquaintance of German- American portrait artist Winold Reiss, who illustrated the March 1925 New Negro issue of Survey Graphic for Locke. Locke recognized that the sculptural art of Africa had inspired the art of such leading modernists as Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brancusi and that it could lead to the creation of great art by African Americans. Both Reiss and Locke encouraged Douglas to develop his own American black style from design motifs in African art.

Douglas followed their suggestions and sought examples of African art, which in the 1920s were beginning to be purchased by the collections of American museums and galleries.

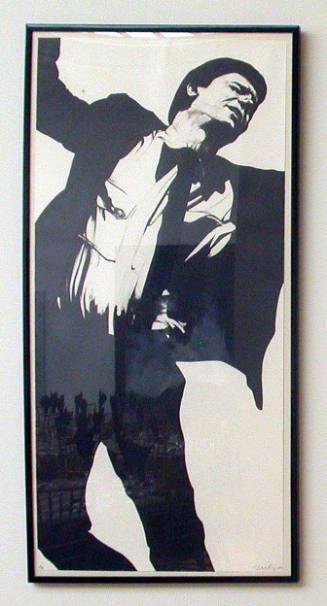

Murals and drawings were his primary works, focusing on religious customs and favoring a geometric style which he developed in the 1920s while studying under Reiss. Douglas reduced forms to their fundamental shapes, such as circles, triangles, and rectangles, and tended to represent both objects and black people as silhouettes. Most of these forms are hard-edged and angular, reminiscent of the Art-Deco designs popular in the United States during the early twentieth century. S ome figures, however, have a curvilinear character, apparently influenced by the contemporary Art Nouveau trend in France. Their sense of movement has been compared to that of Greek vase paintings.

Douglas's entry into the art world came in 1925 illustrating Opportunity magazines cover, and a first-place award from The Crisis magazine for his drawing The African Chieftain.

In 1927, his visual exploration of African motifs and his use of black subjects attracted the attention of black intellectual and writer James Weldon Johnson, who commissioned Douglas to illustrate his book God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (1927). Douglas considered his work for this book to be his most important and mature set of illustrations. Douglas said, "I tried to keep my forms very stark and geometric with my main emphasis on the human body. I tried to portray everything not in a realistic, but in [an] abstract way, simplified and abstract as . . . in the spirituals."

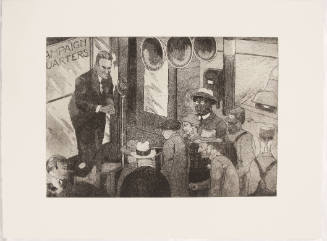

Soon after the completion of the illustrations for God's Trombones, Douglas executed for Club Ebony a mural series inspired by Harlem's night life. Like his illustrations, the mural was done in black and white. Art collector and historian Albert C. Barnes was impressed with the murals and remarked that Douglas should try doing them in color. He offered Douglas a year-long scholarship to study color at his art school outside of Philadelphia, and Douglas, who had very little experience in mixing colors, accepted. As a result of this study, Douglas became to incorporate color into his murals.

Aspects of Negro Life, in 1934, at the Cullen Branch of the New York Public Library is Douglas best-known mural series and consists of four chronological compositions. The first, The Negro in an African Setting, highlights the African heritage of African-Americans through representations of African dance and music. The second spans three stages of African American history: slavery, emancipation, and Reconstruction. The Idyll of the Deep South, the third composition, portrays the problem of lynching and how African Americans, in spite of this omnipresent threat, continued to work, sing, and dance. The final mural, Song of the Towers, charts three events: the mass migration of blacks to northern industrial centers during the 1910s, the flowering of black artistic expression in 1920s New York City known as the Harlem Renaissance, and the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

The technique used in the mural became his signature style a series of concentric circles expanded from a fixed point, imposing figure elements on its background and altering a person's or object's shade of color in the places where it intersected with a circle. As a result, a person or object would bear several diffused shades of the same color. This procedure lent to Douglas's murals a mystical, dreamlike quality. This chromatic complexity and sophisticated design of Aspects of Negro Life is noteworthy compared to others done during the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP), the New Deal program that supported unemployed artists.

Douglas was not exclusively an illustrator and a muralist, although these two mediums occupied the majority of his career. A Rosenwald grant took him to Paris in 1931, and influenced by a year of independent study at the Académie Scandinave there, he occasionally painted portraits and landscapes, which were more naturalistic than his other work.

A second grant allowed him to tour Haiti and the American South in 1938. Douglas was also a social activist who, as the first elected president of the Harlem Artists Guild (1935), worked to obtain WPA recognition and support for African American artists.

As well as a painter, he was an educator, and after graduating from the University of Nebraska, taught art at Lincoln High School in Topeka, Kansas, from 1923 to 1925. Beginning in 1939, Douglas occasionally taught drawing and painting at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. After earning a master's degree in art education from Columbia University in 1944, he became a permanent member of the Fisk University faculty, serving as a professor and chair of the art department there until his retirement in 1966.

One of the first African American artists to affirm the value of the black experience, Douglas continued to lecture and paint until his death, stating his refusal "to compromise and see blacks as anything other than a proud and majestic people."

Aaron Douglas died in Nashville in on February 3, 1979.

Person TypeIndividual