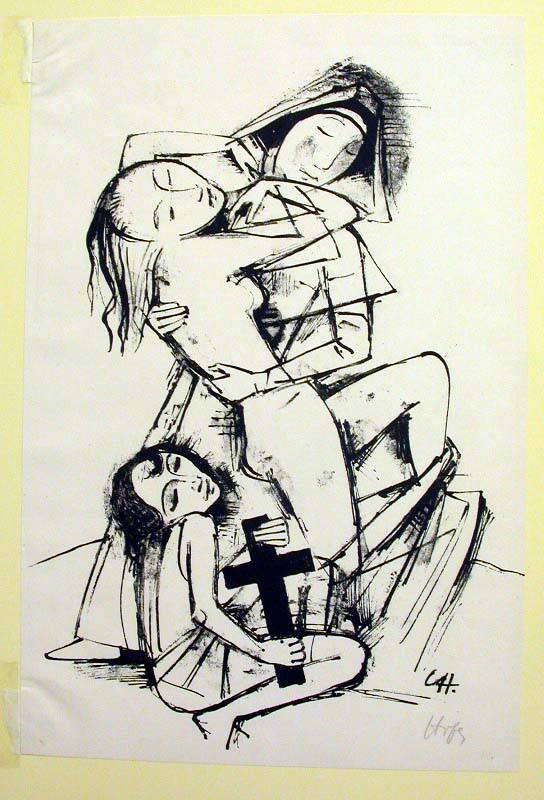

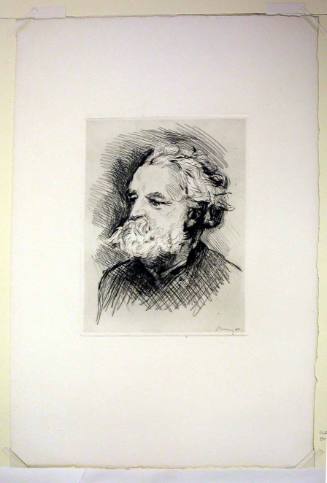

Carl Hofer

German, 1878 - 1955

German painter, draughtsman and printmaker. He was brought up by two great-aunts and later in an orphanage because his father died when he was still an infant, and after leaving primary school he became apprenticed to a bookselling business in Karlsruhe. He began to draw at this time, visiting the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe and (with the help of the mother of his friend Leopold Ziegler, who later became a philosopher) obtaining a scholarship at the Grossherzogliche Badische Akademie der Künste in Karlsruhe in 1897. He learnt little from the painters who taught him, Robert Poetzelberger (1856–1930), Leopold Kalckreuth and Hans Thoma, and instead was influenced by the paintings of Arnold Böcklin. Hofer made the first of his prints in 1899, eventually producing 17 woodcuts, 69 etchings and 190 lithographs closely related in style and subject-matter to his paintings. On travelling to Paris in 1900 on a scholarship he came into contact with Impressionism and the work of Paul Cézanne, but he was little affected by them. On returning to Germany he became a postgraduate pupil of Hans Thoma, following him to Stuttgart in 1902. One of the few paintings of this period not destroyed by Hofer is Children at Prayer (1901), a genre picture in the style of Thoma; its arrangement of people as in a still-life in an indeterminate space anticipates features of his later work.

In summer 1901 Hofer painted a portrait of the poet Hans Reinhart (1880–1963) and through him met the Reinhart family in Winterthur; their financial support enabled him to study in Rome from 1903 to 1908. Few of his paintings of this period, mainly of nude girls and boys based on Classical models, have survived. One of the best examples is Three Bathing Youths (1907; Winterthur, Kstmus.). Travelling through Italy with Hermann Haller and the Italian sculptor and painter Ernesto de Fiori (1884–1945), he was particularly impressed by Pieter Bruegel I’s Parable of the Blind (1568) in Naples, which left its mark especially on his work of the 1940s and 1950s, and by frescoes (1873) showing views around Naples by Hans von Marées at the Stazione Zoologica research institute in Naples.

In 1908 Hofer left Rome for Paris on the advice of his friend Julius Meier-Graefe, in order to develop his sense of colour by familiarizing himself with the paintings of Delacroix and Cézanne. At the invitation of the Reinharts he made two journeys to India in 1910 and 1911, producing mainly drawings. He settled in Berlin in 1913, but during World War I he was interned in France; Theodor Reinhart (1849–1919) helped obtain his release in 1917, upon which he moved to Switzerland. There he discovered the scenery of Ticino, which became a constant motif in his paintings, as in Ticino Landscape (1925; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig); he regularly spent the summer months there until the late 1930s, painting landscapes of this seemingly Arcadian world, which appears hospitable in spite of being devoid of human figures. These pictures, generally simple and balanced in their compositional structure, contain echoes of Cubism and Pittura Metafisica.

Some of Hofer’s finest works, on generalized humanitarian themes, date from the 1920s. In the early 1920s he concentrated on unpretentious figure groups: couples, girls with their arms around one another, young men playing cards and pictures such as Circus People (c. 1921; Essen, Mus. Flkwang) and Masquerade Painting (1922; Cologne, Mus. Ludwig). Company at Table (1924; Winterthur, Kstmus.) is typical of these works in its use of an indeterminate space within which to portray people in relaxed contact with one another, suggesting human solidarity. In the second half of the 1920s Hofer became more concerned with conveying symbolic meaning, concealing dark prognoses of approaching disaster within scenes such as Harlequin, Dummy and Skeleton, Yellow Dog Blues (1928; Switzerland, priv. col., see Rigby, fig.) and The Black Rooms (1928, second version, 1943; Berlin, Tiergarten, N.G.). It was during this period that Hofer gained official recognition, becoming a professor at the Vereinigte Staatsschulen für Freie und Angewandte Kunst in Charlottenburg, Berlin, in 1920 and a member of the Preussische Akademie der Künste in 1923. In 1928 retrospective exhibitions of his work were held in Berlin and Mannheim to mark his 50th birthday. He visited the USA as a German representative on the jury of the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh in 1927 and found the urban life of New York particularly fascinating. He was awarded the second prize of the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh for Pastoral (1933; Frankfurt am Main, Elisabeth Furler priv. col., see Rigby, fig.) in 1934 and their first prize for In the Wind in 1938.

Hofer briefly adopted an abstract style in 1930–31 but quickly returned to symbolic pictures of fate. In late June 1934 he was dismissed from his teaching post and subsequently forbidden to paint or exhibit his work. Some of the 311 works by him confiscated from German institutions were displayed in Munich in 1937 at an exhibition of ‘degenerate art’ (see Entartete kunst). In 1943 a bomb destroyed about 150 paintings and 1000 drawings in his studio; he produced new versions of a few of the most important of these, such as The Black Rooms, working from photographs. In Black Moonlit Night (1944) he summarized the destiny of his generation, which was to wander round as homeless sacrifices beneath a gloomy starlit sky.

Hofer’s reputation was rehabilitated at the close of World War II with his appointment as Director of the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Berlin-Charlottenburg, and he held a one-man exhibition in 1946. He painted several theatrical pictures of ruins and tried to come to terms with the fact of the war and the inseparably linked questions of guilt and responsibility. With the exception of Atom Serenade (1947; Berlin, Elisabeth Hofer priv. col., see Rigby, fig.), his pictures of this period, such as Cain and Abel (1946; Ettlingen, Schloss) and Death Watch (1949; Berlin, Elisabeth Hofer priv. col., see Rigby, fig.), all relate to the tradition of the memento mori, but are directed specifically towards those who escaped accepting blame for their actions.

Hofer’s decisive role in the cultural life of Berlin after World War II was reflected in many honours bestowed on him. In 1948 he received an honorary doctorate from Humboldt University, in 1950 he became President of the Deutscher Künstlerbund, in 1952 he was made a member of the Order ‘Pour le Mérite’ in the peace class, and in 1953 he was awarded the prize for art of the city of Berlin. The Berlin ‘Festwochen’ festival organized a large exhibition in honour of his 75th birthday. Despite this recognition Hofer felt misunderstood, as his art was relegated to the background by the visible dominance of abstract painting. His polemical attack on abstraction, published first in the periodical Der Monat and then in the Berlin daily newspaper Der Tagesspiegel, led to a break with his colleagues and provoked an equally polemical reply from Will Grohmann. Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Fritz Winter and Willi Baumeister resigned from the Deutscher Künstlerbund in protest against Hofer, with whom they never became reconciled. He died in the middle of this debate about the meaning and value of abstract art.

Angela Schneider. "Hofer, Karl." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T038450 (accessed April 27, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual