Max Slevogt

German, 1868 - 1932

German painter, printmaker and illustrator. His father, adjutant and friend of the future Prince Regent, Luitpold (1821–1912), died when Slevogt was just two years old. His mother moved to Würzburg, where he spent his schooldays. Even in his childhood and adolescence, family connections brought Slevogt to Pfalz, to an aunt in Landau and to the Finkler family in Neukastel. Initially he had planned to become a musician, but he began to study painting at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich in 1885. His fellow students included Gabriel von Hackl (1843–1926), Karl Raupp (1837–1918), Ludwig Herterich (1856–1932) and Wilhelm von Diez (1839–1907). In 1889 he spent a term at the Académie Julian in Paris. At that time Impressionism had very little effect on him. Following a trip to Italy in 1890 with the painter Robert Breyer (1866–1941) who had befriended him at the Akademie, he began to work independently as a painter in Munich. In 1893 he participated in the first exhibition of the newly founded Munich Secession, exhibiting Wrestling School (1893; Edenkoben, Schloss Villa Ludwigshöhe); the judges wanted to refuse this painting as immoral since its entwined and naked men caused offence. In the following years his paintings often appeared harsh and non-academic to conservative Munich circles. At this time Slevogt also made contributions to the journals Jugend and Simplizissimus, which were significant in the development of his graphic work. In 1898 he married his childhood friend Antonie (‘Nini’) Finkler. In the same year he went to Neukastel and on an autumn trip to an exhibition in Amsterdam of Rembrandt’s work with the art historian Karl Voll (1867–1917). Voll instructed him in the history of art and published the first monograph on him in 1912.

In 1899 Slevogt exhibited Danaë (1895; Munich, Lenbachhaus) in the Munich Secession, and his triptych The Prodigal Son (1898–9; Stuttgart, Staatsgal.) in the Berlin Secession. Although he aroused disapproval in Munich, in Berlin he was warmly applauded. Berlin was on the point of becoming an international art centre and was attractive to Slevogt. The city was also dominated artistically by Max Liebermann. In 1900 Slevogt visited the Exposition Universelle in Paris, in which he was represented by his large-scale painting Sheherazade (1.37×1.92 m, 1897; Munich, Neue Pin.); there he was impressed by French Impressionism and drawn to its plein-air technique, which he adopted for his own work. Before moving to Berlin in 1901, he stopped off in Frankfurt am Main for a few months and painted the superb Frankfurt Zoo series, including the various versions of the Parrot Keeper (1901; e.g. Hannover, Niedersächs. Landesmus.). These are important pictures in the history of modern German painting, and in them Slevogt demonstrated the influence upon him of Impressionism.

The move from Munich to Berlin occurred during a decisive phase of Slevogt’s artistic development. He entered the art scene in Berlin as a highly respected young artist, already distinguished by the royal title of a professor from Prince Regent Luitpold and inspired by liberating artistic ideas. In Manet’s work he had learnt to see, as he himself put it, ‘what makes the world so beautiful’ (Johannes Guthmann) and thus achieved the brightness and pervasiveness of light that became characteristic of his painting. In 1901 he painted Summer Morning—Woman with Parasol (Edenkoben, Schloss Villa Ludwigshöhe) at Neukastel, which encapsulated all those qualities, and which was immediately shown the following year at the Berlin Secession. Lovis Corinth also came to Berlin from Munich around this time.

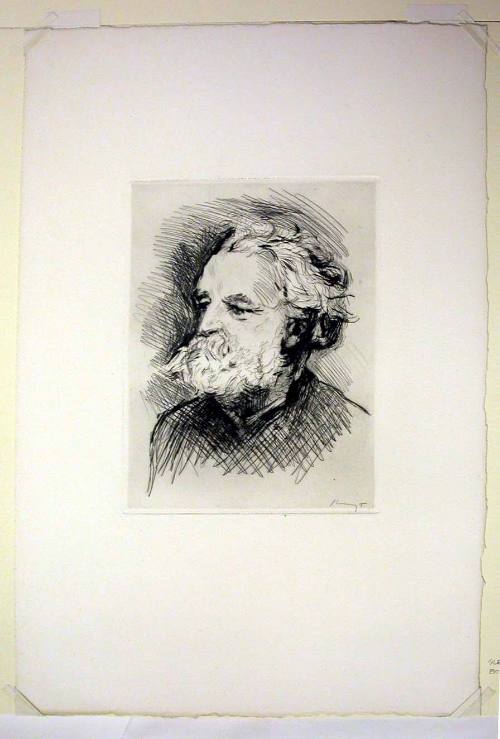

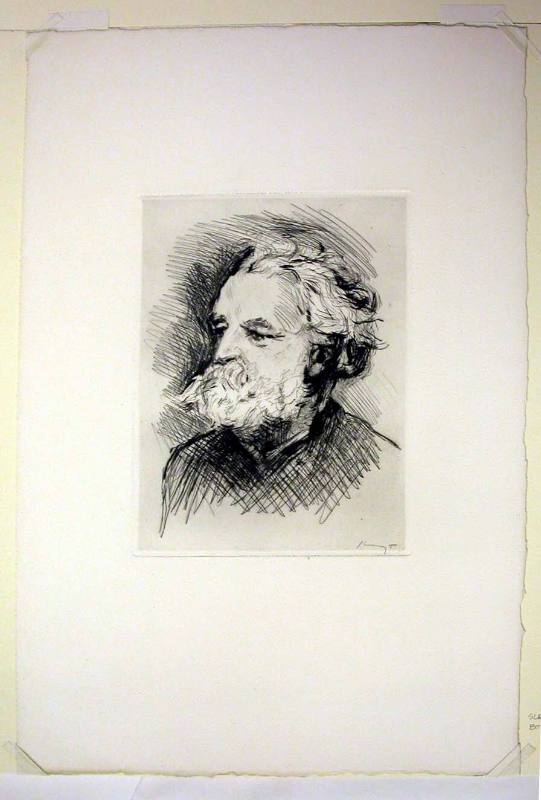

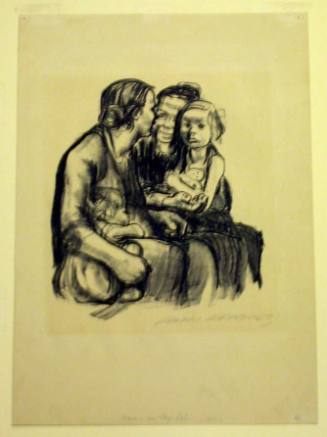

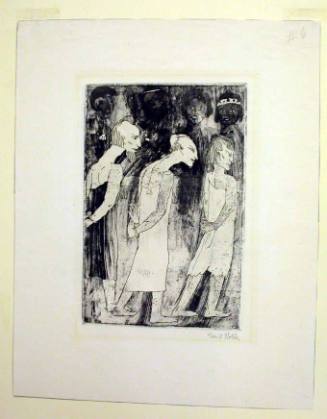

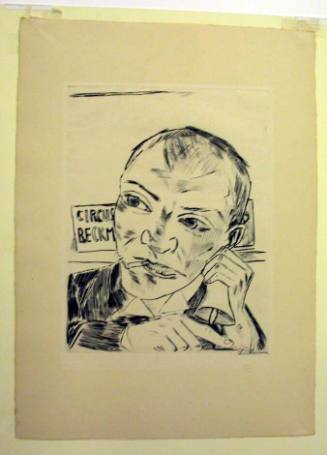

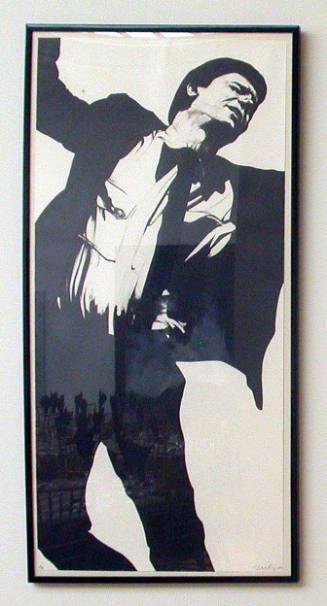

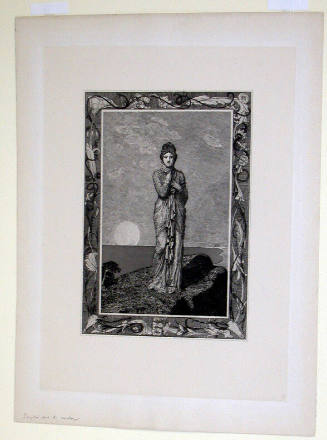

Slevogt was scarcely in Berlin before he had become one of the leading artistic forces there, and he joined the Board of Governors of the Berlin Secession. He also fitted into the social scene and met the Portuguese singer Francisco d’Andrade, whom he had admired before their acquaintance. For him d’Andrade was the unsurpassable embodiment of Don Giovanni in Mozart’s opera. A close friendship grew out of the meeting, and in 1902–3 Slevogt produced the excellent representations of d’Andrade, including White d’Andrade (Stuttgart, Staatsgal.), which became known as the Champagne Song after the aria in the opera, a new ‘portrait of an acting role’ (Imiela, 1968). During this period, in addition to painting, Slevogt became a master of the arts of printmaking and illustration. Bruno Cassirer (1872–1941) and Paul Cassirer recognized at an early stage Slevogt’s ability to create a ‘new style of illustration’ in Germany. His major body of graphic works began around the turn of the century after his arrival in Berlin and continued until the end of the 1920s. He produced a superb range of illustrated books, valuable portfolios, book reprints and popular editions, which became sought-after collectors’ items. The first works were drawings for Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves—Improvisations, prepared before 1900 and printed in Berlin in 1903 by Bruno Cassirer. These were followed by the six etchings known as Black Scenes (Berlin, 1904–5), 15 lithographs of Achilles (Munich, 1907), 33 lithographs of Sindbad the Sailor (Munich, 1908) and 312 lithographs of J. F. Cooper’s Leather-Stocking Tales (Munich, 1909) from Pan Press in Paul Cassirer’s publishing house. Slevogt’s reputation as an illustrator was based on these marvellous works. The question soon arose of whether Slevogt was more important and greater as a painter or as an illustrator and printmaker. His painting and graphic work complement each other so closely that one can be related to the other, although they are quite separate achievements.

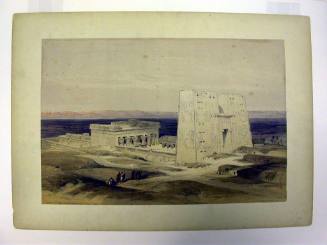

A key date in Slevogt’s life was 1914. He went on a trip to Egypt with his friends Johannes Guthmann (1876–1956) and Eduard Fuchs (1870–1940). His artistic output during this period amounted to 21 paintings and numerous watercolours. These represented peaks in German Impressionist painting. His most recent experiences of light were translated into his paintings. These works were acquired by the Dresden Galerie (now Gemäldegalerie Neuer Meister). On his return from Egypt, Slevogt took ownership of Neukastel (now Slevogthof), which he had loved from his youth, from his parents-in-law’s estate. At the outbreak of World War I he volunteered for military service as a war artist. He returned, shattered, after a few weeks: ‘An overriding memory of a world that seemed violated by blind destruction was all that remained of that participation, for which I had so fervently longed’ (Ein Kriegstagebuch, 1914, published 1917). In 1917, when Slevogt was appointed Head of a master studio at the Preussische Akademie der Künste in Berlin, he produced the series of 21 lithographs Visions, a tremendous condemnation of the war. After the war he felt isolated, suffering greatly by being unable to return to Berlin from French-occupied Pfalz. Slevogt helped himself to get over this period with his Marginal Drawings for Mozart’s ‘Magic Flute’, illustrations for Mozart’s original score. The 47 etchings are among his most enchanting works. The Magic Flute series was published by Paul Cassirer (Berlin, 1920). In 1918 his illustrations with 125 lithographs for an edition of The Conquest of Mexico by Hernán Cortés were published. From 1918 he illustrated Grimms’ Fairy Tales, and in 1921 he produced 57 lithographs for The Wak-Wak Islands from the fairy-tale collection A Thousand and One Nights; this had fired Slevogt’s imagination since his childhood, and in the lithographs he attempted to capture the erotic atmosphere of the East using all the subtleties of the medium.

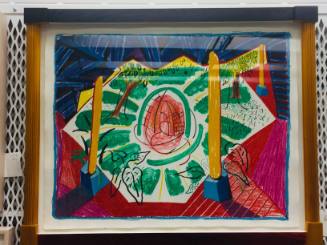

In 1924 Slevogt painted murals in his music room at Neukastel, including scenes from Mozart’s Magic Flute and Don Giovanni, from Wagner’s Siegfried and Weber’s Der Freischütz, which kept the musically talented and enthusiastic Slevogt occupied all his life. In the same year he produced nine lithographic stage designs for a production of Don Giovanni at the Dresden Staatsoper (1924; see Rümann, no. 65), and also a series of etchings known as A Passion, an important contribution to 20th-century religious art. From 1924 to 1927 he worked on a huge illustration project for Goethe’s Faust II with 510 lithographs and 11 etchings. The way in which Slevogt managed to integrate the text and images is quite remarkable. This was followed by 13 two-colour lithographs for Macbeth. Reineke of 1928, with 12 etchings, concluded the series of Slevogt’s etchings. In 1929 he painted the ceiling of the library that he had built on to Neukastel with the theme of literature of the world. Four genres of creative writing, corresponding to the pictorial repertoire of Baroque painting, are represented by figures from classic literature; a scene from A Thousand and One Nights with the narrator Sheherazade for the fairy tale; a quotation from Macbeth for drama; Achilles, dragging Hector round the walls of Troy, for the epic; and Cooper’s Leather-Stocking Tales, set against an illusionistically painted balustrade, for the novel. In 1931–2 Slevogt designed and executed the Golgotha Fresco in the Friedenskirche in Ludwigshafen am Rhein, which was destroyed in World War II. This huge mural of the Crucifixion was a major work of 20th-century religious art and is considered to have been one of Slevogt’s greatest works. On his death Slevogt was buried in the Finkler family grave in a wood at Neukastel.

Berthold Roland. "Slevogt, Max." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T079186 (accessed April 27, 2012).

Person TypeIndividual